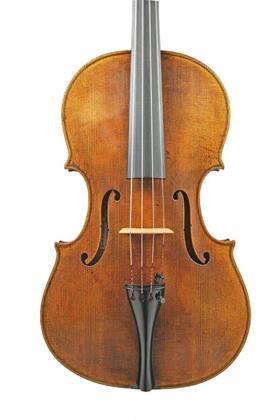

Tips and opinions from The Strad's archive on capturing a classic look in new instruments – or not

A roller coaster of emotions can be felt when antiquing. Sometimes it can look horrible and daunting, and make us want to quit. At other times it starts to look better and we suddenly feel like we might know what we are doing. However, instrument makers should never be betrayed by those emotions and should persevere whether it looks bad or better, only stopping when it looks right.

Regardless of how authentic we try to be, none of us will be fortunate enough to let a violin wear naturally for 300 years. Sometimes antiquing requires a little bit of faking and trickery.

Jeff Phillips and Antoine Nédélec, The Strad, July 2013

I favour the patina and craquelure that goes with the look of an antique instrument but tend to steer away from making instruments that masquerade as genuinely old. I use oil-based varnish because, although there is no conclusive documentary evidence, I feel this is more historically correct.

My own recipe for varnish is composed of copal and mastic with oil added as a plasticiser, turpentine as the vehicle and, for colour, Madder Lake with a minuscule amount of Burnt Umber occasionally added.

Paul Harrild, The Strad, March 1996

I feel strongly that antiquing an instrument reinforces the idea that old instruments are best. I think a new instrument should be able to stand up and say 'Here I am, I’m brand new,' and should be proud of that fact. Convincing reproductions are hard to make and a badly conceived reproduction can turn what originally may have been a good instrument into an ugly mess.

Paul Bowers, The Strad, March 1996

On many old Cremonese violins it looks like the varnish has chipped off. We use packing tape to reproduce the majority of this effect. This is heavily influenced by the type of varnish used (tough varnish will not release easily, if at all, and overly brittle varnish can release too easily).

By pressing tape against the varnish and pulling away, it can be removed in large or small quantities. It’s good to work this step over the whole instrument, and not just the typical wear line. If one area of the instrument has considerable chipping (the centre of the back, for instance), most other areas will also have at least some chipping.

Jeff Phillips and Antoine Nédélec, The Strad, June 2013

After using gouges and thumb planes in the usual manner, I resist using too much scraper or sandpaper just to smooth the surface. Instead, I focus on creating a final shape without hiding the process of getting there. Just as wood takes on a natural texture, so the tools themselves leave marks in the surface.

The tool being used, the direction of the cut, even the sharpness of the blades – everything tells a story in the wood. Because tools and work habits are different for every maker, my instruments take on a more personal look than if I sanded everything flat. Adding tool marks back to a sanded surface looks rather contrived to me. But natural tool marks help give the look of age that is so charming on classic Italian instruments.

Gregg Alf, The Strad, December 2010

There is some basis to believe that 300-year-old wood has undergone chemical or physical changes similar to what can be produced in a short time by thermal processing. In my experience, the greatest change in properties is with a strong process, but you end up with wood that is extremely dark, brittle, very difficult to work cleanly and likely to be more prone to accidental damage. Acoustically, if the gains are not balanced, the sound will not be quite right.

Don Noon, The Strad, January 2012

I struggle with the challenge of leaving a high-quality surface that at the same time is not too shiny. On most old violins, even when they have been polished, the surface shine is broken up into many facets that give a softer appearance to the eye. A flat, mirror-like shine seems hard in comparison.

Although sheen can be adjusted somewhat by the resin and particulate content of the varnish, I find that the most effective way of maintaining a soft look is to retain the natural texture of the varnish itself. I do that by sanding minimally between coats with a flexible abrasive that floats over the surface rather than levelling it.

Gregg Alf, The Best of Trade Secrets, 2012

The numerous experiments tried in order to arrive at maturity by artificial means are not worthy of consideration at this day, but in times gone by great store was set on the wood being 'prepared'. Enthusiasts baked the wood, steamed it, pickled it, treated it with acids, caustics, spirits and what-not too numerous to mention.

Arthur Broadley, The Strad, May 1920

I recommend that you get rid of the sandpaper and think twice before picking up a scraper. Violins are made with cutting tools, and I don’t go to a lot of effort to hide that. I am happy to leave obvious toolmarks in my woodwork, as they provide opportunities when varnishing. Remember that what looks textured in the white will be much less so once varnished – you need to overstate things a little.

The scroll is a pretty obvious place to leave gouge marks. I don’t get too carried away when refining the sides of the pegbox as I like to leave some opportunities there, too.

When antiquing, dirt is pushed into any indentations, be they scratches, chips or toolmarks, to recreate the effect you see on old instruments. All those toolmarks we left before varnishing now become opportunities to add some patina to the surface, add contrast and depth to the colour, and to soften the overall look.

John Simmers, The Strad, November 2018

3 Readers' comments