The French soloist and teacher advises on how to improve intonation and dexterity on the double bass. From the October 2015 issue

I’ve never played using anyone else’s technique – I developed my own. When I was 15 years old and playing the bass, I was out of tune every time I shifted. Then I thought to myself, ‘If I let the left thumb act as a pivot, I can reach the same notes but I won’t play out of tune. If I move my thumb, it’s a hazard.’

If you pivot your hand, you can reach three notes in the lower positions; if you play in the traditional way, you can only reach two. You only need to change your hand position once to play three octaves, instead of having to move every two notes. In higher positions you can learn to play a whole octave scale without shifting, just by pivoting from your thumb, opening your hand and using your fingers to crawl over the fingerboard like a crab. It means that you never have to slide, you can play more quickly and fluidly, and you will make fewer mistakes.

This is particularly important for fast, clean playing. If you’re playing something slow and singing, you can do the whole thing on one finger and move as often as you like. I teach this to all of my students.

For every scale there are over a hundred possible different fingerings. Experimenting with these will help you to understand the double bass better – to discover which strings and fingers to use to make the music sound as you would like. You can change the same phrase many times by doing this, and it will help you with your musical interpretations later on.

When you begin using the pivot technique, start in third position. Here your left hand can assume a more relaxed position and reach more notes than it can in first position, without having to stretch too much. Now, rather than shifting, pivot from the thumb, opening out the hand to reach notes that are traditionally in a ‘new position’. Gradually increase the breadth of this movement over time, making sure that you are always relaxed.

Play exercises 1, 2 and 3 with each of the alternative fingering suggestions, making sure that your left hand does not move throughout each of the horizontal square brackets and instead pivots from the thumb. Where fingerings are circled, the finger in question should stay in place until the succeeding finger has been putdown.

Repertoire

In composition, who is bigger than Bach? The crab and pivot techniques are particularly important when playing the Cello Suites on the bass, to achieve a clean sound without slides. Try playing the section of the Allemande of Bach’s Second Cello Suite shown in the below example, using the fingerings marked. Your hand should remain open, as shown in figure 1. In general, I will never teach a student to play repertoire in my way – they must develop their own ideas and choose their own fingerings. I only show them how to achieve the sound that they want. Each one of us can say the same thing differently. I give students the chance to say it in their own way, by giving them a good technique. If they have nothing to say, I cannot help them.

In your practice

To play the bass, you must build up your muscles bit by bit, so that you have the endurance to play for two hours without stopping. At first, play for a few minutes at a time; then build it up week by week. It took me around two years to build up to two hours.

If you go on vacation for a week, you will have to begin again or you risk getting tendonitis. Start with half an hour, then one, then one and a half, then two. Always be careful. I never play for more than two-and-a-half hours per day.

On a concert day, I do not touch the bass before the performance – I warm up on the public. That is because you have to give your audience something more than just notes: they must cry when you play; they must be touched by each note. You cannot do that if you have played for hours beforehand and you are tired.

If you are struggling with something, ask yourself: ‘Why can’t I do that?’ Is it your bow, your finger, the string? Sometimes your instrument will react to the weather, and if something is going wrong it may not be your fault. If it’s very humid and my hands are getting stuck, I use Vaseline, although it can be a little slippery if you use too much.

If you play a note out of tune, it is too late to fix it. Go on, then be more careful next time you play that passage. Rectify each error little by little. Never move your finger when you have already landed, because the ratio of movement to space and time is not correct. You must know at the beginning of the movement where you are going and how fast, so that you play correctly first time without hesitation. When you play correctly, stop – don’t repeat. Just think, ‘How did I do that?’ and record the feeling in your muscle memory.

Add to what you know; don’t change it. Even a bad habit might be useful one day. You may learn an infinite number of new movements, but those you have already learnt – good or bad – are engraved in your muscular memory forever, like walking. A bad habit that produces a nasty note could be useful, if it can be reproduced when needed. In Strauss’s opera Salome, for instance, we have to illustrate the singer chopping off John the Baptist’s head. Here we need to produce a grinding note, not a vibrating one.

Notes for teachers

When any professor tells a student to do something, they have to explain why, because it will open the student’s eyes and teach them new things. When I see somebody play, I know immediately what to say to correct whatever is going wrong. Many players are only using ten per cent of their potential as musicians. Open their eyes and show them a way to use everything they have; teach them how to move their bodies to achieve the right pitches and sound. The bow and the student’s arm are one; the student is the bass. Students cannot develop their sound without having that image.

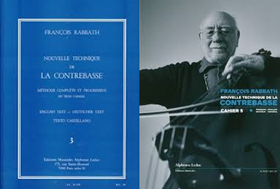

You can find more information on the crab and pivot techniques in the third book (far left) of my New Technique for Double Bass series. The fourth book gives very varied scale and arpeggio fingerings to help you to build a more flexible technique.

Repertoire examples can be found in book five (left).

This article was first published in the The Strad's October 2015 issue

No comments yet