Colleagues Sam Zygmuntowicz, Colin Gough and Jim Woodhouse share their memories of the well-regarded British luthier and acoustician, who died on 25 December 2024

Discover more lutherie articles here

The British luthier, gut string maker and acoustics expert George Stoppani died on 25 December at the age of 75. A world-renowned figure in the field of instrument acoustics, he created software and measurement spreadsheets that are now used by violin makers across the world. Here, three of his colleagues who worked with him at the Oberlin Acoustics Workshop and other international gatherings remember their friend and collaborator.

Sam Zygmuntowicz

Violin maker, NY, US

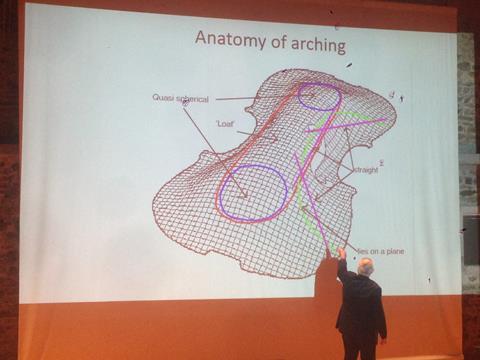

I first met George at the Oberlin Acoustics Workshop in 2007, where he introduced us to his modal analysis software and methods. I remember his initial presentation where he showed us a familiar ‘sound spectrum’ graph, but which he then rotated in previously unimagined three-dimensional ‘Nyquist’ space, with the sound resonances displayed as irregular spirals. The room was completely silent, until someone hesitantly asked, ‘Is that what is really happening?’ George wryly answered, ‘In a matter of speaking, yes.’ Over the years I found this to be a typical experience with George, where the familiar was shifted to reveal an unexpected beauty and complexity which lies beneath the vibrating surfaces of the violin. He showed all this with an artist’s eye and an intuitive gift for visual communications.

George was an indispensable bridge, able to master technology and collaborate with scientists on significant experiments, but also happy to help violin makers with practical questions. He was also keen to improve his own instrument making and materials. George had an uncanny and obsessive ability to teach himself the most complex skills, including computer programming and the advanced mathematics necessary to do acoustics research. His curiosity led him to develop his own software programs. Like a Prometheus, his generosity in freely sharing his acoustic software put new abilities directly into the hands of violin makers.

His self-directed ingenuity infused a wide scope of interests, including martial arts, string making, tool design and varnish making. I often felt that his mind was far ahead of my own, yet his openness and wry humour made it a pleasure to be his friend. Every visit with him included hours of sketching out ideas on napkins or scraps of paper, as well as endless discussion. I will miss all that beyond measure.

Read: British luthier George Stoppani has died

Read: ‘A perfect mind obsessed with understanding the quality of violins’: a tribute to George Stoppani

Read: Analysing the ‘Boissier, Sarasate’: Stradivari à la mode

Colin Gough

Emeritus professor of physics, University of Birmingham, UK

George was a man of many parts and a very close friend and collaborator. As an acoustician and violinist, I have been hugely inspired and supported by George, enjoying our mutual interest in the acoustics and history of the violin and related instruments. I also own one of his fine-sounding violins.

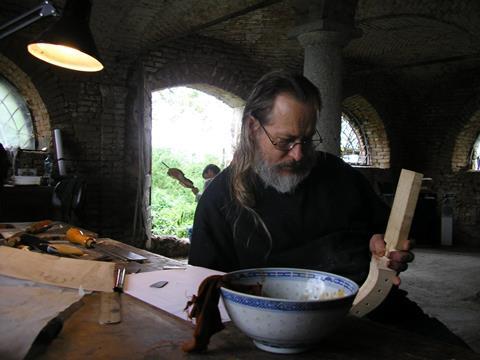

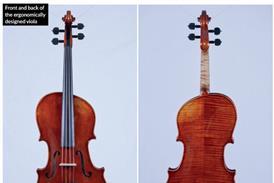

After a degree in literature at York University, George joined a hippy community supporting himself doing farm work. In parallel, he was learning the carpentry skills required to make copies of Renaissance and other early stringed instruments. This ultimately led to him to become an exceptionally fine maker of acoustically informed copies of classic Italian instruments of all sizes. Based on historical research, he also developed strong views on the types of gut strings used on instruments during the Baroque and earlier periods. As a result, he set up his own commercial facility to make ‘authentic’ gut strings for early-music string players. He was still working on new instruments and making gut strings until only a few months before he died.

Despite his non-scientific education and largely arts and humanities background – his father was a painter and his mother a sculptor – George taught himself advanced computing skills. He used them to develop a powerful set of professional-quality software programs, specifically designed and freely available for violin makers and researchers. The software was used to measure, analyse and vividly display the acoustical vibrations of the violin and other instruments. The measurements involved gently tapping the violin at many points on the surface of the violin and measuring the response at the top of the bridge. His unrivalled expertise in measuring and analysing the acoustical properties of the violin and other instruments made him an invaluable central figure in the large number of collaborative projects and workshops that he was invited to join. This made huge demands on his energy and time, which was always given unstintingly, even when he was becoming seriously ill.

George contributed hugely to my research using computer modelling to investigate the vibrational modes of the violin and other instruments. As a result, we were jointly able to identify and understand the important radiating modes of the violin family and several other historic stringed instruments pre-dating the violin.

Read: Making Matters: Optimising sound spaces for good acoustics

Read: Trade Secrets: A workshop facility to measure violin family acoustics

Read: ‘Makers should pay attention to these three modes’ - Joseph Curtin on violin acoustics

Jim Woodhouse

Emeritus professor of mechanics, materials and design, University of Cambridge, UK

George’s contributions to the technology of measuring violin response were remarkable. His background was decidedly non-technical, but he became fascinated by modal analysis. Not having the resources to buy commercial software, he taught himself to program, and over a period of years he produced an impressively sophisticated computer package. The result was far superior to commercial codes, from the perspective of a violin maker. For example, commercial code would typically produce animations of mode shapes using a rather crude wire-frame representation. George’s code incorporates features including the details of f-holes, corners and so on – with the result that his pictures look like real violins, and indeed recognisable individual violins.

At the same time he built up experience himself with making measurements, interpreting them and incorporating the results into his making practice. His own making matured and blossomed. He also collaborated with many of the scientists working in violin acoustics. Over time, he became a leading guru of practical violin acoustics through his involvement with the Oberlin Acoustics Workshops, the Villefavard workshops in France, and the BELE Violin Making School in Bilbao, Spain. He delivered high-profile talks at academic conferences on technical acoustics and online through the Oberlin Acoustics talk series.

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stringed instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet