You’ve reached the final round of an orchestral audition, now what? Following his first two articles on approaching auditions, conductor Leonard Slatkin guides players on what comes next

Read Leonard Slatkin’s previous articles here:

Flying Blind: A conductor’s guide to taking an audition

Flying Blind: A conductor’s guide to taking an audition, part two

Congratulations! You have surmounted the first few hurdles of the process and made it all the way to the finals. This round will involve only a handful of candidates and, if the audition is for a section position, the orchestra may have more than one vacancy to fill. Your chances are looking pretty good.

The first question is usually, ’When are the finals taking place?’ Sometimes, depending on the schedule and how many players advanced to the semis, the finals might be held later the same day. Often, the final round takes place the following day, giving you a night to mentally prepare. You now have almost all the information you need, although the finals involve some key differences. The music director will be there, for starters.

The audition might last for up to 20 minutes, perhaps more if you are contending for a titled position, such as a principal player or assistant section leader. The screen might come down for this round, as a few orchestras have implemented recently, increasing the opportunities for communication between the audition committee and candidate. For example, when I was starting out in the profession, I appreciated the option to approach the stage and give the finalists guidance if they were playing an excerpt differently from what I would prefer. Everyone could see each other, lending a degree of comfort to the proceedings, which are admittedly still stressful.

It is critical to understand the exact nature of the job, especially a position within the violin section. Some orchestras may list a vacancy for ’violin,’ while others will specify ’first’ or ’second.’ You may wish to find out if the successful candidate will rotate chairs and stand partners throughout the season. For most players, this is not a problem, but others strongly prefer the stability and familiarity of fixed seating.

At this stage, and perhaps even before, it is wise to ask for a copy of the collective bargaining agreement. Some orchestras want you to decide on the spot if you are going to take the position, and you must be prepared for this possibility. Knowing the rules and regulations governing a particular ensemble could be a determining factor.

Back to the audition itself: You may now be asked to play part of not just one but two concertos, one of which might be a piece of your choice from the canon. The other will be by Mozart, if you are a violinist. I understand the theory, but what if Mozart’s solo works are not really in your wheelhouse? These days, with the sheer variety of music played by any orchestra, should we pass judgement based on a flawed performance of the A-major concerto? Still, it is usually required, so make the best of it. I prefer to hear the G-major concerto.

Usually, one concerto is enough for the violists, cellists, and double bass players, although cellists could also be asked to play one of the two Haydn concertos. However, this is when solo Bach repertoire comes into play. Just as violinists are asked to play one of the solo sonatas or partitas, a similar requirement typically applies to the lower strings, not so much to assess the style of performance but rather to evaluate intonation and clarity. Solo Bach pieces also give the committee a good idea of the quality of your instrument.

Excerpts from the orchestral repertoire will follow, and in this round, you will play more of them. Continue to show individuality, coupled with an understanding of the character of these pieces. For example, during violin auditions, I always listened for an outstanding spiccato in the Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the feeling of a long line in the third movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and sustained, in-tempo playing in the opening of Brahms’s First Symphony. Likewise, violists can demonstrate their use of tone color in the opening of Mahler’s Symphony No.10, cellists can display their keen intonation in the ‘Offertorio’ from Verdi’s Requiem, and bassists can show their dynamic range in Act IV of Verdi’s Otello.

Orchestras reserve the right to add sight-reading, but I rarely saw it enforced in my time as a music director. This should be brought back, in my opinion, given how many concerts are played with just one rehearsal. In addition, Pops and film scores present many challenges, and I think some of this music should be included at auditions. John Williams is not easy.

The finals audition for a principal position will test candidates’ knowledge of the orchestral repertoire as well as their solo skills in all styles. You will likely be asked to play chamber music with other members of the string section. You don’t know them, and they don’t know you, so part of this is a guessing game. Just try to fit in, but if you are vying for a concertmaster job, show strong leadership. This can be a turning point in the audition, as it might be the only time you play in an ensemble.

However, as a top candidate for a principal position, you will most likely be asked to participate in a one-week trial during which the full range of your skills will be on display. This will be scheduled when the music director is leading the ensemble. Sometimes, you might be asked to play a movement of a concerto as well.

Now that you have completed your part of the bargain, there is nothing to do but wait. The committee may make a decision immediately or reconvene the next day to sort out the many pieces of the puzzle. If you get the job, great—assuming you are sure that this orchestra is the right fit for you. If they don’t make you an offer, please remember that your goal should be to do your best. You cannot control how others think and feel. Use what you have learnt for the next time. More opportunities await.

In these articles, I have expressed my opinion on what to expect during auditions based on years of leading orchestras as a music director. Everyone will have their own ideas about how the process plays out, so I encourage you to gather as much information as possible to be prepared for any outcome.

Best of luck to you all.

Read: Fake it ’til you make it: The art of orchestral faking

Read: ’There is little to no room for error’: Sightreading in a recording session orchestra

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

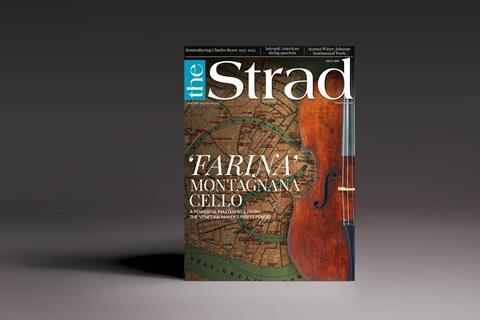

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

1 Readers' comment