Violinist Tomás Cotik shines a light on forgotten composer and cellist Ennio Bolognini through rediscovery and exploration of the work Serenata del Gaucho, which contains demanding and virtuosic pizzicato from the performer

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Some years ago, I heard my colleague at Portland State University, cellist Hamilton Cheifetz, playing a piece that immediately resonated with me. Though I was hearing it for the first time, the Argenintinean folkloric music sounded familiar, echoing memories of home. I soon discovered it was Serenata del Gaucho by Ennio Bolognini, who I had not heard about until that point. I listened to a few other recordings—Bolognini’s own, and one by his student, Christine Walevska—but found no transcriptions for cello, let alone for violin. Learning this piece one day remained high on my bucket list.

During my recent sabbatical last year in Spain (thanks to a Fulbright award), I reconnected with a dear old friend, Luciano Di Renzo. I had known him as a very talented young violinist back in Argentina. We had met in different parts of the world as each of us followed our careers, and he was now teaching in Madrid. I mentioned Serenata del Gaucho, and he generously offered to transcribe it for violin. Within days, he presented me with this remarkable gift, which I eagerly learnt and recorded upon returning home to Portland, Oregon.

This piece fascinates me, evoking vivid memories of the first place I called home, with sounds that are rarely heard in my current life. It takes me back to a place I left almost 30 years ago and maybe even has some Flamenco inspiration that now brings me fond memories of my incredible sabbatical year in Spain.

In Argentina, a ‘gaucho’ is a traditional term referring to a skilled horseman or cowboy, known for their expertise in cattle herding and rural life on the Pampas, the vast plains of Argentina. Historically, gauchos emerged in the late 17th and 18th centuries as independent, often nomadic figures who symbolised the rugged, self-sufficient lifestyle associated with the countryside. They are revered as symbols of Argentine national identity, embodying traits such as bravery, loyalty, and freedom. Gauchos have a unique culture, including distinct dress, music, and dance, and they play a significant role in Argentine folklore and literature. Because historical gauchos were reputed to be brave, if unruly, the word is also applied metaphorically to mean ‘noble, brave, and generous.’

The title Serenata del Gaucho captures this spirit of the gaucho—an emblem of resilience and cultural pride in Argentina—making it an evocative choice. The association between gauchos and the guitar is well-documented in Argentine folklore and cultural history. They often played music in the evenings or during social gatherings to accompany folk songs and traditional dances, such as the Milonga and Zamba, integrating guitar-based folk traditions like the Payada (a form of musical dueling with improvised lyrics), into gaucho culture.

Playing this piece on violin is uniquely challenging, as it mimics the guitar, which requires intricate pizzicato techniques that are unlike anything else in the violin repertoire. I use nearly all my right fingers in different ways and combinations to achieve various pizzicato effects, sounds, and colours. Sometimes, I use my thumb for a bold yet cushioned sound. Other times, I use the typical index finger and sometimes the middle finger, which I find has a warmer, more resonant sound.

I often use ‘rasgueado,’ a back-and-forth strumming motion across the strings in a controlled way with the index or middle finger, down with the fingertip and up with the nail. This strumming motion is employed at different speeds and sometimes in different combinations, like two downs and one up, to create different emphasis.

Depending on speed and desired sound, I sometimes need to keep the finger loose or tighter. In some instances, I keep a finger touching the fingerboard for hand stability and reference (anchoring the thumb when plucking with the index finger, and the middle finger when plucking with the thumb). Otherwise, I keep the hand floating above the strings, allowing the arm to be involved in the motion all the way from the shoulder.

Playing this piece on violin is uniquely challenging, as it mimics the guitar, which requires intricate pizzicato techniques that are unlike anything else in the violin repertoire

A few times, left-hand pizzicato works perfectly for a fast scale going down. Other times, I perform a sort of roll, doing a fast downward strum with pinky, ring, middle, and index fingers in that order. This works great for a fast figure of four notes like a triplet followed by a quaver note. Doing so with only three fingers, starting with the ring finger, can help to execute a fast two-note appoggiatura landing on the beat with the index.

Close to the beginning of the piece, I even use arguably the fanciest pizzicato technique, a tremolo pizzicato inspired by Hungarian violinist Roby Lakatos, where both the middle and then the index finger go successively one way and then the other; two down, then two up, repeated. It’s quite tricky and unlike anything else.

It was an entertaining journey to figure out which pizzicato fits best at each moment. The difficulties of performing this piece lie in quickly switching between different pizzicato techniques and fingers, as well as in accurately catching the specific strings that need to be highlighted while executing bold, fast motions. The transitions from arco to pizzicato and vice versa also require special attention.

At the start of the piece, I leave the bow lying nearby on a music stand, giving my right hand more freedom. Later in the piece, I quickly grab the bow to play the arco sections and manage the successive pizzicato sections while holding the bow, which imposes some restrictions on movement and slightly alters the overall weight and sound.

Pizzicati tend not to project as well in the hall, so we need to ensure they are both audible and clear, while also considering how the microphones will capture them if we are recording. Unlike the cello– Bolognini’s own instrument for which he wrote this piece–the violin has higher tension and shorter strings, posing the challenge that pizzicati are less resonant. Nevertheless, I find it all worth it—the challenge of replicating, on the violin, colours and sounds that are more typical of the popular guitar music from Argentina. Serenata del Gaucho is a gem of a piece, crafted by a man who was, himself, equally as unique and intriguing.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1893, Bolognini was a virtuoso cellist, admired by contemporaries like Pablo Casals, who called him ‘the greatest cello talent I ever heard.’ Gregor Piatigorsky even proclaimed, ‘No, I am not the greatest cellist in the world; neither is Feuermann. The greatest is the Argentine Bolognini.’ And Feuermann himself said: ‘For my money, the world’s greatest cellist is not Casals, Piatigorsky or myself, but Bolognini!’

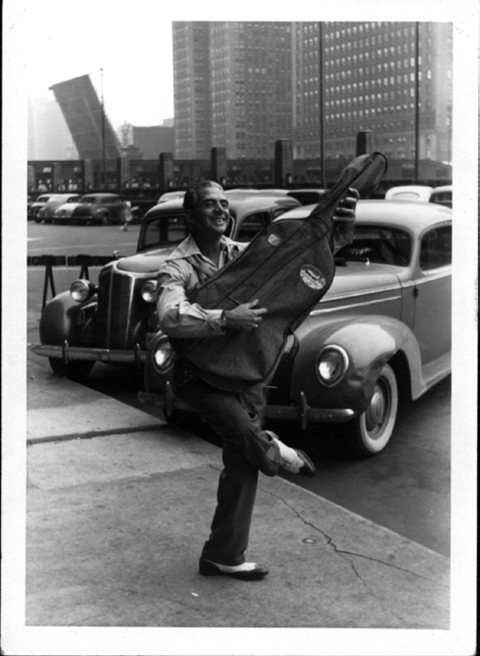

Bolognini defies categorisation. Beyond his musical talents as a cellist, composer, and his skills in piano and guitar, he was also a professional boxer, fluent in several languages, an expert in gourmet cooking, a pilot, and an instructor. He helped pioneer aviation in Argentina, making a flight in a free-floating balloon, and even built a plane with a friend. Later on, he trained cadets during World War II and co-founded the Civil Air Patrol.

After training at the St. Cecilia Conservatory in Buenos Aires (with Jose Garcia Jacot, teacher of Casals) and winning an international cello competition at age 15, he performed alongside composers including Saint-Saëns and Strauss. His career brought him to the US in 1923 to serve as a sparring partner for Luis Firpo in preparation for Firpo’s legendary world heavyweight championship fight against Jack Dempsey. He also played other sports including golf, soccer, and polo, and was even a bronco-buster.

After the bout, Bolognini remained in the US, joining the Philadelphia Orchestra and later the Chicago Symphony. Known for his charisma, he was also quite eccentric, bringing his dog to rehearsals and playing flamenco on the cello.

Later in Las Vegas, he established a symphony orchestra and continued his aversion to recording, preferring the ephemeral nature of live music, which explains why many in my generation had not heard of him.

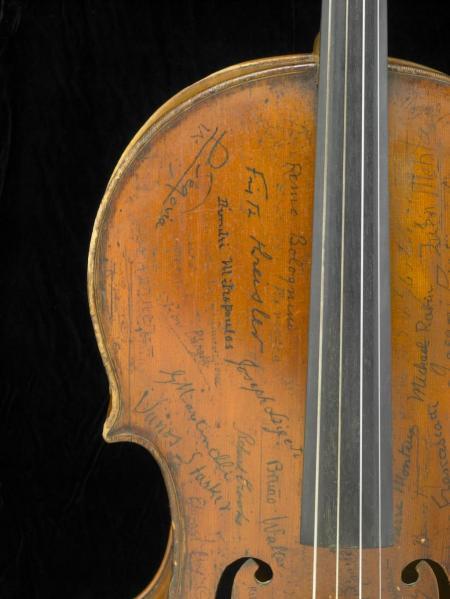

Ennio Bolognini‘s few compositions and equally few recordings, as well as his cello–covered in 51 ballpoint signatures from legends like Toscanini, Casals, and Kreisler–remain curious testaments to his remarkable life.

Picture credits: from the Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Read: Opinion: why don’t string players practice pizzicato?

Read: 7 pointers for perfect pizzicato

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

1 Readers' comment