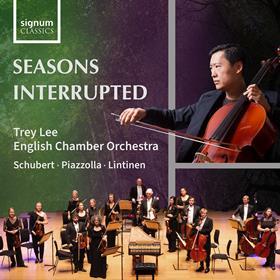

Trey Lee discusses the climate crisis through the lens of music across the eras, in line with his new album Seasons Interrupted, out on 17 May

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

I have always thought of music as a way to tell stories, though mostly in the form of non-verbalised sonic abstractions. However, my new album Seasons Interrupted - available now on Signum Records - has allowed me to construct a narrative that expresses something that is becoming more palpable with the passing of the seasons: anxiety from the looming climate crisis. From a young age, I was already imagining a plan B in an elevated mountain cabin should the ice caps melt irreversibly. This feeling is by no means exclusive to myself; mental health experts are labeling it not as a disorder, but a rational reaction to something real and beyond our control. Some demographers attribute low fertility rates partly to climate anxiety - why would you want to bring a child into a world with such an uncertain future?

Today, the cultural zeitgeist is progressively catching up to the scientific realities of climate change. The nonprofit consultancy Good Energy reports that this phenomenon is showing up more often in films and books, and not only as the villain in sci-fi fantasies; they are part of narratives in everyday life that we can all relate to. It notes, ’The more that we see (climate change) included or highlighted…the more likely we are to really prioritise it, to think about it as a public issue that demands attention and immediate action.’

As part of these narratives, Seasons Interrupted delves into climate anxiety and explores the four seasons across three distinct periods: the past, the present, and the future. Drawing inspiration from the works of Franz Schubert, Astor Piazzolla, and contemporary Finnish composer Kirmo Lintinen, this album is a collection of pieces that reflect how the seasons have changed over time.

The album begins with four Lieder by Schubert, selected for their depictions of a time when nature was more predictable. These compositions serve as a reminder of what once was - a world where the arrival of spring, the warmth of summer, the falling leaves of autumn, and the hibernation of winter were steadfast and reliable. While other composers have also explored seasonal themes, I was particularly inspired by Schubert’s frequent practice of borrowing melodic material from his vocal works; this is found in some of his most monumental instrumental compositions such as the ’Death and the Maiden’ quartet, the violin Fantasy, Trockne Blumen, and of course, the ’Trout’ Quintet.

In this spirit, I transcribed these four songs for the cello, relying on its oft-praised vocal quality to cast a new light on Schubert’s melodies. The poetry served as an interpretative guide that influenced much of the way the music was performed; for instance, in Herbst, the words ’die Geliebte’ indicate that the singer is lamenting a female beloved, but the original text from Ludwig Rellstab’s poem had ’den Geliebten,’ or a male beloved. It is not clear whether Schubert deliberately chose to change the voice to that of a man, or whether indeed he wanted it to be about two men, but I took this opportunity to keep Rellstab’s original object of affection as a man, cast the cello in the role of the female lover - a likely choice given the social norms of the era - and raised its voice by one octave to a more feminine range.

Read: Feeling powerless as a musician in the face of the climate crisis? 6 ways to take positive action

Read: A Change of Season: spotlighting the climate emergency through music

Next, we confront the present with Piazzolla’s Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas (Four Seasons of Buenos Aires). These works mirror our modern-day lifestyle of excess and decadence, intertwined with sensuality and violence. Piazzolla’s music captures the essence of contemporary society, where the seasons begin to blend into one another, blurring the lines between them. When I was rearranging this work from the original, I sought to create a unique version whereby the cello occupied a space somewhere in between the expressive coloratura of the violin and the dignified elegance of the bandoneon. The result is a cello part that has to be masculine and feminine, soulful and dispassionate, fierce and tender. At times, the cello reaches for the stratosphere in the blink of an eye; at other times, it takes on the role of an unflappable and austere bandoneon, tossing off improvisatory passages nonchalantly. One can almost visualise the tanguero heaving and twirling his partner around the dancefloor during these sequences.

Finally, though Lintinen’s Cello Concerto was not composed specifically in the context of the climate crisis, it portrays a world teeming with tensions that shift relentlessly from darkness to light. With that in mind, I set out to recontextualise it within the narrative of this album - namely, for the concerto to represent an imaginary post-climate-change world where the four seasons are not correlated with the four movements. Indeed, there are no seasons to speak of, but simply a musical journey from despair to hope.

The first movement, ’Inizio - Dystopia,’ imagines a dystopia ravaged by climate change, with the solo cello struggling to rise above the gloom. ’Gavotte - Modulation/Mutation’ briefly looks back at the past - specifically the Baroque period - before returning to the environmental catastrophe ahead. In the third-movement cadenza, the cello symbolises defiance in the midst of the cataclysm. ’Salvation,’ the finale, alludes to the torment of climate change but ultimately re-introduces our longing for the end of the climate crisis, which bonds all of humanity.

My one reservation for the Cello Concerto was this: In each performance there is a need to navigate a delicate balance between respecting the composer’s original artistic vision and creating a personal interpretation, infused with a unique perspective and emotional resonance. In the end, it felt possible to do both with this concerto, and in doing so, it allows the work to be heard from novel viewpoints.

One might say this is a quixotic attempt to find a purpose for a cellist and his music in the face of an overwhelming global crisis. Nevertheless, I find it heartening to be part of a collective of narratives about climate change, sharing the same anxiety and hope for change.

Seasons Interrupted is out now on Signum Classics. Find it here: https://lnk.to/SeasonsInterrupted

Read: ‘Art has the ability to make one look at the world from a different perspective’ - cellist Trey Lee

Read: Postcard from Hong Kong: Musicus Fest

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet