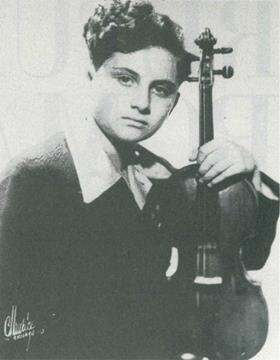

Aaron Rosand The US violinist and teacher recalls a nerve-racking performance and hands on some advice drawn from his many years under the spotlight

Early in my career I received a call asking me to substitute, at a week’s notice, for an ill Joseph Szigeti in his New York concerts with Thomas Scherman and the Little Orchestra Society. I accepted the opportunity without hesitation. The catch was that I had no knowledge of the repertoire: the Busoni Violin Concerto and Berlioz’s Rêverie et Caprice.

It took two days just to track down the scores and my violin did not leave my hands for several days afterwards. For three days of rehearsal I played with the music, but on the day of the performance I walked out on stage with just my violin. Vanity was an important factor and I couldn’t bring myself to use a music stand in concerts, but when the orchestra began the long tutti at the start of the Busoni Concerto my mind suddenly drew a blank and I couldn’t remember the first notes.

I looked up to the heavens and said to myself, ‘If there is somebody up there, please get me started!’ When I did begin to play it was like an out-of-body experience. The performance was broadcast and recorded and, to this day, I cannot believe how impeccably it came off.

THE WISEST THING ANYONE EVER TOLD ME

When I was twelve years old, my great teacher Leon Sametini told me to focus my attention on my bow arm. ‘Your left hand is a machine,’ he said. ‘Your right hand produces tone and nuance, and adds style to your playing.’ This advice has served me well throughout my long career. What I would have told myself, though, would have been to expand my knowledge and learn to speak other languages. Communication is of vital importance for establishing an international reputation. Keep in touch with those responsible for concerts in all parts of the world – not just conductors and orchestra managers but also the patrons who support their very existence. After-concert parties are just as important as the engagements themselves, and can lead to re-engagements.

THE HARDEST LESSON I’VE HAD TO LEARN

Put simply, the most difficult thing I had to learn was how to practise efficiently. Hours can be spent on difficult passages that have been removed from their contexts. The ultimate goals are learning how to work in longer sections and how to apply technique to achieve a musical result. Efficient practice requires total concentration on the music with no distractions or unrelated thoughts in your mind.

The enormous pressure to practise continuously so you can meet your high personal expectations precludes any time for your own personal pleasure. You must eat and sleep music to achieve the highest goals, since there are no short cuts in the world of violin playing. Studying all branches of music making (such as opera and orchestral music) and developing a knowledge of the great composers is an endless task in the quest for honest and personal interpretation.

First published in The Strad, December 2017

No comments yet