The sound of massed violins underpins the music in thousands of Indian films. Tim Woodall traces the instrument’s colourful history in Mumbai’s film industry

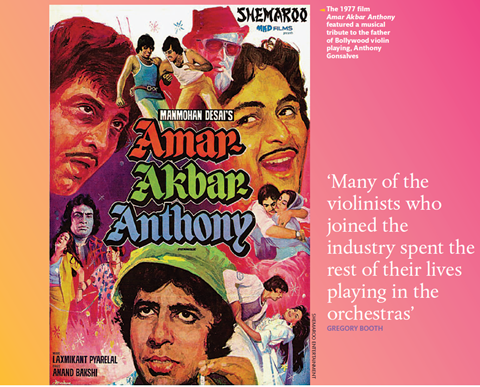

The story of the violin in Bollywood is at times a strange one. A suited man in a top hat, umbrella in hand, steps out of an egg-shaped pod into what looks like a wedding party and starts to sing. A song-and-dance routine follows. The infuriatingly catchy melody is played by a full studio orchestra. When the camera focuses on the female star, the object of the singer’s attention, a group of violins plays a falling rhythmic figure of the sort heard in hundreds of Bollywood films. The song, ‘My Name Is Anthony Gonsalves’, from the 1977 film Amar Akbar Anthony, is significant because it was an unusual musical tribute to the father of Bollywood violin playing.

Born in 1927 in the Portuguese colony of Goa on India’s west coast, Anthony Gonsalves was one of many Goan musicians who tried their luck in Bombay (now Mumbai) during the Second World War, shortly before Indian society was transformed by the independence movement. It was a time of profound cultural change, says New Zealand-based academic Gregory Booth, author of Behind the Curtain: Making Music in Mumbai’s Film Studios: ‘There was a big touring circuit based on British culture. Dance and jazz bands and light classical music groups played in clubs across India and on to Dhaka, Singapore and Sri Lanka. Most of these players were from Goa, where there was music education in the church schools. After independence in 1947, all of a sudden these bands needed visas and the work dried up.’

Musicians like Gonsalves instead turned to the Bombay film studios, where productivity was soaring post-independence. Different cultures combined to contribute to the emerging Bollywood song form that would dominate Indian cinema for more than 30 years. The Hindu songwriters and Muslim lyricists in Bollywood relied on mainly Christian Goan arrangers and instrumentalists. Although they earned their livings playing in the studios, many Goan violinists, who didn’t speak Hindi, were rather snooty about the Bombay film songs. Gonsalves was different. ‘He actually loved the music he was playing,’ says writer Naresh Fernandes, author of a book on the city’s jazz age, Taj Mahal Foxtrot. ‘He soon graduated to doing arrangements for composers around the city.’

With no history of Western musical education for Hindus in Bombay, the Goans also became teachers, tutoring locals, some of whom straight away played for studios that were churning out films at a rate of knots (Bollywood was fast developing its partly justified reputation for quantity over quality at this time). ‘Whatever we learnt was on the spot while working in the industry,’ recalls Amar Haldipur, one of Bollywood’s most prominent violinists, on starting out. ‘We were working, learning and playing all at the same time.’ Although Gonsalves made his name bringing Western symphonic influences into Bollywood, his great legacy was as a violin teacher of both humble session musicians and future Bollywood legends.

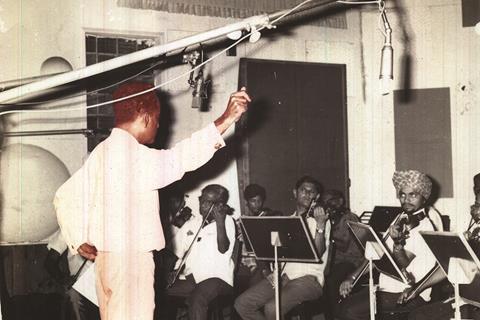

Film composers in Bollywood are known as ‘music directors’ and they enjoy a status similar to the director of the film itself. In what is often referred to as Bollywood’s ‘golden age’ of the late 40s to the late 60s, music directors composed for huge orchestras that combined Western and traditional instruments. Two of the most famous music directors at the time were Gonsalves pupils: R.D. Burman and Pyarelal Ramprasad Sharma, who was one half of a composing duo known as Laxmikant–Pyarelal and the composer of the tribute song ‘My Name Is Anthony Gonsalves’. The orchestras assembled by these directors were on a grand scale. ‘Laxmikant-Pyarelal used to have around 45 violins at one time for live recordings,’ says Amar Haldipur. ‘And if it was a big production, there could be 60 or 70 violins, along with a woodwind section of 30, a rhythm section, including tabla, and a chorus of 60.’ Booth estimates that there would have been between 200 and 300 violinists living off Bollywood during this period, many of them Hindu players taught by Gonsalves. ‘Many of the violinists who joined the industry spent the rest of their lives playing in the orchestras and a lot of them worked non-stop,’ says Booth.

There are arguments as to whether Shree Pundalik (1912) or Raja Harishchandra (1913) was the first Indian film. But either way, Indian cinema is roughly a century old, as indeed is Hollywood. While it developed concurrently with its American cousin, the Indian film industry went very much in its own direction, bringing together Western and local influences to create films that are uniquely Indian. Nowhere is this more evident than in Bollywood music. Indian traditions of folk theatre, dance and song have always been the key ingredients of Bollywood films, more so than drama. With the introduction of talkies in the 1930s, the importance of music and song grew and the phenomenon of the ‘playback singer’ emerged, with film stars lip-synching to songs sung off-screen. Playback singers such as Lata Mangeshkar (who arrived in Bombay at about the same time as Anthony Gonsalves), Asha Bhosle and Mohammed Rafibecame huge stars in their own right.

The songs sung by these artists became, and remain, India’s popular music. And like the films themselves, the music composed for Bollywood’s ‘golden age’ assimilated a jumble of influences. ‘To understand Indian film music you have to look at it like an Indian meal, a freewheeling experience where one course follows another in no particular order,’ says British–Indian author and journalist Mihir Bose, who has written a biography of Bollywood. ‘The music was a mixture of Indian peasant singing, the ragas of Indian classical music, Western popular music forms and Western classical music.’

The violin, introduced to India about 200 years ago, has deep roots in southern Indian classical music, where it has a different tuning system and is played on the chest with the player sitting cross-legged on the floor. Bollywood violin playing is not from this tradition. ‘It is basically the European style of playing, with the violin held under the chin and with Western tuning and notation,’ says Booth. Yet the sound generated by the violin sections in the Bollywood studios is unlike anything you would hear from a Western orchestra. Playing in unison, the strings have a rich, creamy texture, often with long, sliding runs in a high register as a countermelody to the nasal vocals of the main tune.

‘If it was a big production, there could be 60 or 70 violins, along with a woodwind section of 30, a rhythm section and a chorus of 60’ — Amar Haldipur

Studio violin sections would sit in rows in a hierarchy according to experience. ‘They were playing with only one or two mikes in the whole room, so there was a clear distinction between who sat in the first row as opposed to the fourth row, from where you can’t really hear what’s being played,’ says Booth. ‘We know the names of many of the players in the first row, who were responsible for a lot of the sound.’ These players often went on to become arrangers and sometimes – like Amar Haldipur, whom Booth refers to as the leading violin soloist of his day – even music directors.

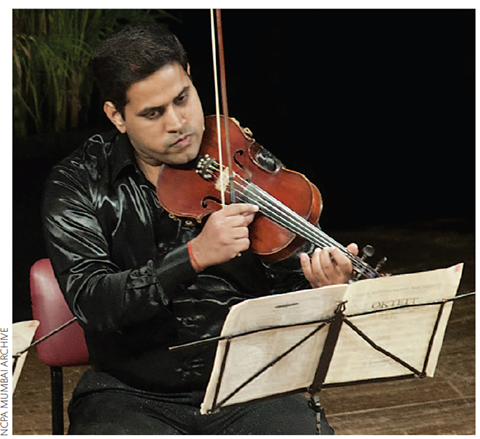

Inevitably, the days of 70-violinist studio orchestras did not last. ‘There were two generations when film song was inescapable,’ says Booth. ‘In that time players could make money through the studios or through touring shows. But those audiences are getting older and kids are growing up on a diet of global pop music.’ Mumbai-based violinist Prabhat Kishore is a second-generation Bollywood violinist. ‘Playing music is my family profession – my father is also a violinist and music director in Bollywood,’ says the 30-year-old. ‘All my relatives are professional musicians, either in Bollywood or in the live shows.’ Yet Kishore’s Bollywood experiences are very different from those of his father. Although he still plays in the studios, like other Mumbai violinists Kishore also plays in the Symphony Orchestra of India, which was established in 2006 and is based at the National Centre for the Performing Arts.

Technology forced change. ‘The early 90s saw the beginnings of multitrack, synthesisers and sequencers and it really became a question of economics,’ says Booth. ‘Directors realised that they didn’t need to hire forty violinists any more – they could hire five instead and multitrack.’ For older players, the advent of electronic music and techniques is a sad reality. ‘There is no future at all for the violin,’ says Amar Haldipur. ‘There is no point in booking session musicians to play fragments that are then sampled. They say the sound is old-fashioned, but those phrases that the violins used to play – you just can’t get that sound on other instruments or by sampling.’ The view from the wider industry is similar. Amarpal S. Gaind is head of European operations at Saregama, India’s biggest recording and music publishing company. He notes that while Bollywood is enjoying wider international influence than it ever has, change has come at a cost: ‘Today, India unfortunately looks more towards the West and the music has changed. The melody has gone.’

Yet the picture might not be quite as bleak as Haldipur and Gaind feel it to be. ‘For big films they use violins to get the original sound that electronics cannot produce,’ says Kishore, who believes that there are dozens of violinists still working in Bollywood, ‘making their living through the studios and live shows’. And although lower-budget films do not use session musicians, the wider presence of Bollywood culture offers opportunities. From dance shows to the musical Bombay Dreams (with music composed by today’s most famous music director, A.R. Rahman) live shows need players. The ‘golden age’ will not return, but the violin is likely to have a place in Bollywood forever.

A HISTORY OF BOLLYWOOD MUSIC THROUGH TEN FILMS

Shree Pundalik (1912) Arguably the first Indian film. Early Indian cinema imitated (and existed alongside) traditional folk drama shows, of which music was an important element.

Alam Ara (1931) The first Indian talkie set the tone for the musical direction of Bollywood films with seven songs.

Kismet (1943) A nationalist classic featuring music by a leading music director, Anil Biswas. The film included a chorus for the first time in Bollywood history.

Awaara (1951) Directed, produced by, and starring Raj Kapoor, probably the biggest name in old Bollywood, Awaara (‘Tramp’) was a big hit. The film included an original nine-minute musical dream sequence that, according to Bollywood music scholar Gregory Booth, required 120 musicians for a marathon recording session that lasted nearly 24 hours.

Mother India (1957) This Hindi epic starred one of Bollywood’s biggest names, Nargis, and had music by Naushad Ali. Playback singers on the film included Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle and Mohammed Rafi.

Mughal-e-Azam (1960) Mughal-e-Azam (‘The Greatest of the Mughals’) was another epic film with music by Naushad Ali. The great Lata Mangeshkar sang on the film’s soundtrack, which is often cited as one of Bollywood’s finest.

Amar Akbar Anthony (1977) A fairytale story of the lives of three brothers, this blockbuster featured music by composing duo Laxmikrant— Pyarelal, including Pyarelal’s tribute to violin teacher and Bollywood composer Anthony Gonsalves.

Bombay (1995) A politically controversial film dealing with the 1993 Bombay riots, with music by the then up-and-coming A.R. Rahman.

Slumdog Millionaire (2008) Although Danny Boyle’s Oscar winner is not actually a Bollywood film, its music was written by A.R. Rahman. Typically for the composer, the soundtrack blends percussion heavy production with traditional Bollywood sounds, including strings.

3 Idiots (2009) Then Bollywood’s highest grossing film of all time, this movie took $70 million worldwide. Its seven-song soundtrack barely features the instrumentation of Bollywood’s ‘golden age’.

This article was originally published in the May 2013 issue of The Strad

No comments yet