The editor Ariane Todes pays a flying but revelatory visit to the string archives of the largest library in the world

What does the editor of The Strad do on holiday in Washington, DC? Why, visit the Library of Congress, of course: home to extensive collections of string players’ archives, including those of Heifetz, Kreisler, Piatigorsky, Koussevitzky and many more. Then there are the violins, which include several Strads, such as the ‘Betts’ and ‘Castelbarco’ violins and the ‘Cassavetti’ viola. Not to mention the amazing scores – seeing the manuscript of the Brahms Violin Concerto with markings made by Brahms himself, and probably Joachim, rates as one of my most remarkable experiences ever.

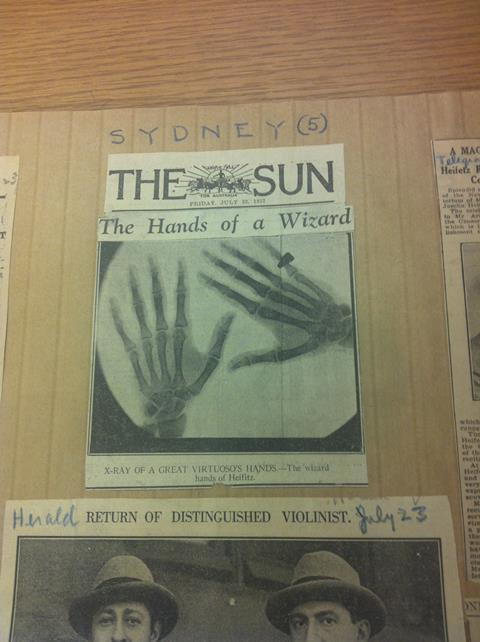

I was shown around by Dario Sarlo, who has just produced the first volume of a new translation of a biography of Heifetz, based on his research at the library. Alas, my visit was short, and I only had three hours to pack in as much as possible. The first of Heifetz’s scrapbooks was revelatory – his own marked up collection of every newspaper article mentioning him from his first world tour, from Honolulu to India. It was interesting to think of the motivation of the young man keeping such fastidious records – pride, vanity, youthful excitement? Who knows. Or is it that different from today’s Facebook interactions? What was as remarkable was his ability to be quoted on a different subject, whatever the journal. Here he is discussing the musician’s education in 1916, in the Los Angeles Times:

‘Music alone is not enough to fill an artist’s life, declares Jascha Heifetz, violinist, who will play here October 20 at the Philharmonic Auditorium. “One must add to it other interests,” he explains. “For myself – books, travel, people, sports – but not politics.”

“Politics are not for the musicians. Fortunately I can speak through music to persons of all opinions and races. I do not need to know their convictions and they do not need to know mine.”

“When I studied at the conservatory in Leningrad, we were not considered properly taught if we knew only our own instruments. We violinists, for instance, had to study something of the piano, the harp and of course the viola. We were required from time to time to play in different sections of the orchestra, for the benefit of our sight reading, and we had to know the theory and technique of performance in duets, quartets, and all forms of musical ensemble.”'

The complete fascination of journalists and audiences throughout the world is less of a surprise, or the consistency with which he was able to perform and of the responses he got. There are some sillier cuttings, including a picture of someone who is certainly not Heifetz, announcing his wedding (which Heifetz has marked with blue question marks) and the December 1917 article in which a physiognomist draws a comparison between Heifetz and Maud Powell:

‘Two violinists! The physiognomist is at once attracted to the two faces by the similarity in the features. The poise of the head is the same, the curly hair, worn more curled in the picture of Miss Powell as befits a woman, the fine, well shaped ear perfectly placed on the head, the eyebrows so distinctly marked and in each case thick at the point of junction with the nose, the shapely nose with the close nostrils, are most expressive of the same shape and expression, as can readily be seen in spite of different positions.’

Also very moving are the letters and telegrams between the greatest players of the time – Menuhin to Szeryng, Casals to Kreisler, Oistrakh to Kreisler. The string playing community was indeed an international fraternity.

Perhaps one of the most revealing letters is one written by Stern to Szeryng in July, 1972. Szeryng was about to take on the young Shlomo Mintz for two weeks of study in his class in Geneva. Stern’s letter and the concerns he expresses about his protégée Mintz’s education is a salutary one for all teachers and young string players:

‘I would be enormously grateful to you if you would let me know what you think of him and if you could help me in continuing the path that has been so carefully prepared over these years. That is, that he should continue his studies and particularly widen them in terms of music history, chamber music and general knowledge because he is an extremely bright boy with a good head. All the remarks and expectations that have already been aroused in Israel must of necessity create an effect on such a young person, even though he seems healthy and outwardly cool. But you know what people are like and how they tend to exaggerate without knowing the enormous dangers and pitfalls that really go into the making of a career. Only those of us who have been through it, in every facet of it, really know what it’s all about.

‘Most of all, I would appreciate it if you would see that he does not appear unduly as a soloist either privately or publicly during his stay in Geneva. He can learn a great deal from you and the experience of being in another country, hearing other young people; watching you work with others and learning to expand his curiosity and hear other standards can be of inestimable value to him. The adulation and praise he gets as an extraordinarily talented youngster has already been there and I really have something of a problem in this respect to convince people to be careful of the values of this kind of adulation at too early a stage in life.

…

I know that I can count on your care in this case and I appeal to you as a colleague to watch over the young man and see that he gains the most of his time but that it goes to his talents and not to his head.’

Too many things to see but I’m already starting to plan my next trip to the Library of Congress!

No comments yet