Violinist Hector Scott examines how players can use scales to exercise curiosity and exploration of musical expressivity, as opposed to excessive, grinding, repetitive practice

’Today’s scientists have substituted mathematics for experiments, and they wander off through equation after equation, and eventually build a structure which has no relation to reality’ - Nikola Tesla

Recently, I have been listening to a podcast by Hallie Rubenhold, Bad Women, which challenges what you thought you knew about Victorian serial killer, Jack the Ripper, and shows a different view of the case by looking at the murdered women rather than the protagonist. Now I am not suggesting that scales hold the same horrors as those perpetrated by Jack the Ripper, although watching a young Erick Freidman being asked by Jascha Heifetz in a lesson to play G flat in 10ths might make most violinists’ bowels rumble, but it made me realise that there is perhaps another way of looking at the development of technique and how scales can be utilised in exploring our musical intention. The ‘chicken or egg’ question that needs to be discussed is whether it is necessary to build a technical foundation initially to facilitate playing musically or whether the very pursuit of our musical intention is what drives the development of technique. The answer probably lies somewhere in between, and it is the navigation of this path between the Yin and Yang that ultimately determines the level of success in our musical endeavours.

In trying to cover the important technical elements we come up against in our practice we are challenged by the dimension of our curiosity and the efficient use of available time. Often, while the time given in this pursuit might not be excessive, the technical elements covered are too restricted. Alternatively, the work undertaken might be exhaustive, but the time taken too excessive. A look at the Flesch Scale System with Rostal’s appendix highlights the vast canon for the left hand that the developing string player needs to attend. However, this is small in comparison to the endless variations that are possible for the right hand.

Again, using the Flesch Scale System as an example, to manage these expectations, he identifies the basic motions of the right arm (recognised by many as the 6 Basic Bowing Exercises): detaché in lower half, detaché in upper half, string changes in lower half, string changes in upper half, and fast small strokes at heel, middle and point. There are also various mixed bowings, martelé, staccato, jumpy bow strokes, and thrown strokes. In addition to this is the need for the musician to enhance their sensitivity or feel of the bow against the string through a diversity of tone exercises focusing on dynamic range, inflection of accents and use of portato.

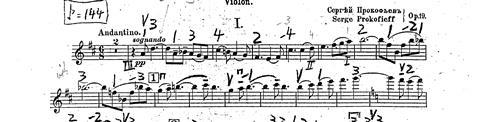

How often would a musician play a sognando scale to explore the balance between a dreamy sound world and a practical volume, as demanded in Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto no.1? Is it any surprise that Brahms sonatas are played with excessive vibrato when trying capture the expressive intent after a musician has been playing scale routine in a ’mind-deadening mechanical manner’?

Capturing the p sotto voce ma espressivo quality of the opening of Brahms Violin Sonata in D minor op.108 takes considerable finesse. Unfortunately, in our world of learning outcomes that are driven into students in UK schools, there is limited time for curiosity and exploration with the execution of the exercise being the primary goal. We want to believe that if we do the right thing, as put forward by the teacher in whom we trust, that good things will happen to us, and we like to justify our outcomes.

’If the structure does not permit dialogue, the structure must be changed’ - Paulo Freire

In his thought-provoking book, The Dynamic Studio, Philip Johnston describes the Static Studio as being on the lookout for new pieces students could be learning as opposed to the Dynamic Studio which is on the lookout for new ways students could be working. His important point is to encourage the student to ‘switch into a highly creative what-if mode of thinking’, rather than setting the student up for ‘repetitive, grinding practice’, often with the focus on time spent.

For teachers, it is important to teach students the values of anarchy. Systems are corrupting and norms need to be called into question. Scales are the purest form of expression and need to be treated with great care and curiosity. It is important to always remind ourselves in our practice of Aristotle’s quote, ‘We are what we repeatedly do’.

Hector Scott is a former student of Max Rostal in Bern and Eric Rosenblith at New England Conservatory. He is associate head of strings at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and was formerly head of strings at Marlborough College

No comments yet