Berenice Beverley Zammit, Graduate Teaching Assistant for Music Performance Psychology at the Royal College of Music, gives guidance on getting back into practice after a year of lockdown

As the COVID-19 lockdown eases worldwide and pub gardens and shops reopen, we are all eagerly awaiting the reopening of theatres and concert halls in the coming weeks.

More than a year has passed in which government measures and public health recommendations have enforced lockdowns and restrictions to help reduce the transmission of COVID-19. These restrictions have had profound effects on performing arts professionals. In the UK, performing venues have been shut for a number of months and any in person artistic engagement has been prohibited, forcing it to either stop entirely or move online from the confines of home. A study by Spiro et al. (2021) investigating the effects of the first COVID-19 lockdown on UK performing arts professionals, reported that 96% of performing artists had spent less time in performing, 90% spent less time in conducting / directing / producing, and 73% spent less time in teaching / coaching / workshop leading / mentoring. Averaging across all areas of work, 71% of performing artists spent less time working than before.

What is of concern as we slowly emerge from lockdown is that 33% of performing artists in Spiro et al.’s study indicated that they had not engaged with any learning / practising / preparing / reflecting in any of their performance mediums, and 42% reported doing less of their usual individual learning and practice / preparing / reflecting. Against this background, an international study by Ammar et al., (2020) investigating the effects of COVID-19 home confinement on physical activity and eating behaviour revealed that physical activity among the population decreased by 38%. Sitting time, on the other hand, increased by 28.6%, with the proportion of individuals who sat more than 8 hours a day increasing from 16% pre- COVID-19 to 40% during confinement. A long period of low physical activity has been long established to result in a loss in muscle mass and general deconditioning. What this means is that in the weeks prior to the re-opening of performance spaces, it is important for performers to work towards resuming their pre-COVID-19 practice routines and to work through their deconditioning to regain their levels of physical fitness pre-pandemic. Take the FIT MUSICIAN survey to help us collect data about physical activity and physical exercise in professional classical instrumentalists before and during COVID-19).**

Regaining your levels of physical fitness pre-COVID-19

A sudden increase in physical activity and a surge in practice time after a long time away from performance will, however, increase the risk of injury. It is therefore important for performers to increase their physical activity gradually. According to Joy (2020), a first step away from sedentary behaviour is breaking up prolonged sitting time, alternating between 30 minutes of sitting and standing. This results in an increase in energy expenditure and metabolic health.

Narici et al. (2020) suggest that the preservation of muscle health can be achieved through a series of regular physical activity combining both resistive and aerobic exercise. In a home setting, resistance or strength training can easily be achieved by using bodyweight and/or elastic bands in high volume repetitions of low to medium-intensity training. A few examples of resistance exercises include push-ups, sit-ups, chin-ups, squat thrusts, lunges and step-ups. Examples of aerobic exercise, which is any repetitive exercise involving the large muscle groups, include burpees, mountain climbers and skipping rope.

Read How to put on a live concert in the time of Covid-19

Read A break from string playing can be a constructive experience

Read What does it feel like to play in a socially-distanced orchestra?

In the weeks leading to a return to performance spaces, performers can use both resistive and aerobic exercises as part of their pre-performance routine. In alternating between resistance and aerobic exercises in a circuit training style, completing a fixed set of repetitions in rapid succession, performers will not only be maintaining muscle health but they will also be developing the muscle mass necessary to return to being physically fit to perform.

Incorporating more physical activity in daily living contributes to overall health. However, one must exercise within one’s ability before they can push themselves further. It has long been established that general health benefits come about with at least 30 minutes of moderate or vigorous exercise on five or more days per week.

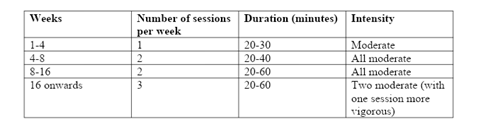

The table below (Williamon, 2012) assumes a sedentary starting point and gives general guidelines for engaging in regular aerobic exercise for aerobic fitness. For those starting at a sedentary starting point, the recommended 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise can be achieved through multiple short bouts lasting only 10 minutes.

The programme above can either be followed by accumulating the suggested session time over two or more shorter sessions that add up to the goal, or by following the programme from its fairly easy start to incremental additions of time, frequency and intensity. It is important to note that starting exercise programmes at unsuitable intensities and frequencies leads to injury and to the untimely dropping out of the exercise regime. A steady approach, on the other hand, will deliver a healthier and more enjoyable experience.

Resuming your practice schedule pre-COVID-19

Avoiding injury is also important when resuming long practice sessions in an effort to return to the performance levels pre-COVID-19. It is therefore crucial that performers pace their return to their former workload in a carefully structured way, gradually increasing practice length and intensity over a number of weeks. During this time it is important to rest as it is to practice. Practice time can be split over a number of 1-hour sessions during the day with an hour’s break in between to allow the body sufficient time to adapt to the new workload. During these breaks it is important to avoid using similar muscle patterns to instrument playing, such as gaming or computer time, as these will increase workload and reduce the chances of a complete rest.

Read Jennifer Pike on performing during the pandemic

Read What does it feel like to give an online chamber concert?

Read The Pandemic Paganini Project: how I decided to fill in the blanks of 2020

Choice of repertoire is also crucial at this point. After a prolonged decrease in practice time good care needs to be taken in rebuilding technique through the right choice of repertoire. Every practice session should be carefully planned in a manner that allows for a steady progression towards the skill levels pre-COVID-19. This can be done by assessing one’s own skill level and by choosing adequate repertoire which is neither too easy nor too demanding to execute without inflicting injury.

It is also important that during this time one monitors the body’s reaction to the workload and proceeds to the next level only when the body feels comfortable with the present load. At this point one also needs to consider slow practice which allows greater attention to sound projection and technique and helps prevent forming new habits and injury.

Mental practice

As a means of taking effective breaks during practising hours while keeping away from activities that further exacerbate the muscle groups needed for playing and also preventing injury, one can resort to mental practice. Practice sessions with learning objectives can be divided into those that can be achieved during a practical session and those that can be achieved during mental practice.

According to advice from the field of sports psychology (Butler, 1996; Syer & Connolly, 1998) in order for mental rehearsal to be effective one should always start with relaxation, so that signals between mind and body are clearly communicated. It is also advised that mental practice be practised regularly, especially in the morning. Regular short sessions are also deemed to be more beneficial than long, infrequent ones but most importantly, one must rehearse specific skills or qualities which are close to one’s technical ability. In rehearsing mentally, one should also use all the senses so that one can feel that they are in the situation executing the skill and therefore mentally rendering the experience as realistic as possible.

A Pre-performance routine

Besides increasing physical activity, physical exercise and practice sessions, in the plan to return to performance one needs to also warm up before playing an instrument. Warming up does not mean playing scales or arpeggios or specific exercises on the instrument, but rather engaging in 5 minutes of stretching exercises away from the instrument. Such exercises can include, but are not exclusive to, stretching the arms above the head, stretching the neck in all directions, arm circling, knee bends, wrist shaking, deep breathing and trunk rotation. The breaks taken between practical practice sessions can also alternate between mental practice and stretching exercises. Cooling down is as important as warming up especially in prevent injury.

Back to work

Although once back at work our lives will become busier and it will become more difficult to find time for physical activity, physical exercise, long breaks between practice sessions and time to stretch and cool down, it is crucial that these good habits are maintained for our own health and wellbeing. It is also important to keep (or return to) a healthy and balanced diet and to practise good quality sleep so as to help our bodies recuperate from micro-injuries and avoid a repair backlog and potential injury.

** We would love to hear from you if you are a professional classical instrumentalist who derives the most part, or all, of your income from work in the following scenarios: postgraduate music students, orchestras, chamber ensembles and freelancers. Please note that this survey is not open to singers. Thank you

Berenice Beverley Zammit is a Graduate Teaching Assistant for Music Performance Psychology I and II, and Performing Arts in Health and Wellbeing at the Centre for Performance Science and at the Royal College of Music (RCM). For more information click here or visit her website here.

Facebook: www.facebook.com/PerformanceGuru

Instagram: @performance_guru_

Twitter: @Perf0rmanceGuru

No comments yet