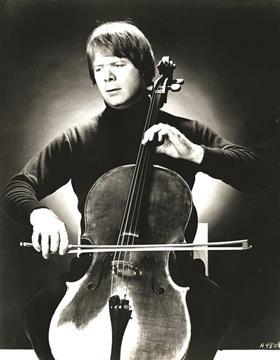

The American cellist looks back at the beginnings of his life as a musician in this article from 2019

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The first person to treat me like an adult was my teacher Lev Aronson. My family moved to Dallas from San Francisco when I was twelve and, when we got there, my mother decided it was time for me to have a male teacher. Up until that point I’d been completely in love with sport, baseball in particular, and would spend hours on end throwing my ball up into the air and catching it in my mitt.

All that changed when I started studying with Lev, whose vast imagination and hugely persuasive teaching suddenly made me realise that I wanted to be a musician, not a baseball player. It was around this time that I would sit down to practise and not realise until I looked up at the clock that I’d been there for over an hour and a half. Up until then, 20 minutes had been my limit! I realised that I had the self-discipline I’d need if I wanted to take music seriously. I find that kind of focus so energising for the spirit, like yoga or deep breathing.

I realised the importance of always keeping an open mind

It wasn’t long after I started as principal cellist of the Cleveland Orchestra that a member of the section complained to me about the way an assistant conductor was rehearsing one of Dvořák’s ‘Slavonic Dances’. ‘He’s doing it all wrong,’ the player said, pointing to a place in the part where he was sure there should have been a ritardando.

When I pointed out that there wasn’t actually anything marked in the music, my colleague replied that he had never heard it played any other way. In other words, he thought his way was right because it was the only way he knew. I realised then the importance of putting aside anything you think you might know about the music, any prejudices or judgements, and always keeping an open mind.

Listening to a cello performance has never been a life-changing event for me. Recitals by violinists, pianists and singers all manage it, as do orchestral concerts. Perhaps it’s because, as a cellist myself, I’m much better equipped to understand what’s going on behind the scenes when I hear good cello playing.

I can find things to admire and things to criticise, but with other instruments I find myself listening over and over again to the same passage to try to work out how on earth they do it.

I had that feeling listening to my father, Mack Harrell, sing the solo bass part in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with the Cleveland Orchestra and George Szell. Years later I played the same piece with Szell and the orchestra, in the days when we had five rehearsals for each concert.

Going through the Symphony with the same level of detail as you would a string quartet was a transformational experience for me.

INTERVIEW BY TOM STEWART

This article was published in the March 2019 issue of The Strad

Read: Great Cellists: Jacqueline du Pré

Read: Obituary: Lynn Harrell (1944–2020)

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet