Bow control and son filé with Simon Standage, professor of Baroque violin at the Royal Academy of Music and leader of the Salomon Quartet

This article was first published in the February 2015 issue of The Strad

I see a lot of young players whose bowing is quite undisciplined. This is partly because of the nature of Baroque music: when playing post 1800s compositions on the modern violin, sostenuto is inbuilt; it’s a basic element of technique. But the language of earlier music is more articulated and this generally applied sostenuto isn’t appropriate any more, so some players think it is OK to play flimsily. From Baroque era reports of playing and teaching, however, it is clear that this was not the case.

When my students start playing ‘fluffily’, I remind them that if you wanted to be in Corelli’s band you had to be able to play two strings at once for ten seconds with a full, steady sound, in one bow – and they had short bows at that time. This tradition was continued by Corelli’s pupil Giovanni Battista Somis, whose ‘single bow stroke lasted so long that the memory of it takes one’s breath away’, according to French violist Hubert Le Blanc – and then by his pupil Pugnani, and by Pugnani’s pupil Viotti.

This in turn inspired Pierre Baillot (1834), who considered practising ‘filer des sons’ to be as essential for the development of bow control as scales are for the training of the left hand – a thought echoed by Ivan Galamian in his 1962 Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching.

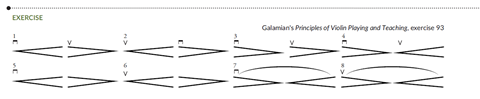

EXERCISES

In early music in particular, every note should be shaped – even the shortest. Once you have acquired some control of your bow speed, there will be a wider range of sound shapes you can make.

The principles below apply whether you are using a modern violin and bow, an old set-up or even a heavy Baroque bow on a modern fiddle, although using modern equipment requires more adjustment. The advantage of using period tools is that you don’t have to make compromises – you can just play for all you’re worth.

Learning to use a slower bow stroke will help you to create musical emphasis, and it will allow you to produce a denser, more intense sound.

- Start by playing the shapes in the exercise below using long, slow bows on open strings.

- Feel the springiness in your right-hand fingers, like the suspension in a car. There should always be a C-shape between the thumb and index finger of your right hand, and nothing should feel tense or stiff.

- Practise each bowing shape while playing two strings at once.

- Now try to make each shape while playing scales, slurring many notes to each bow.

- The bow movement should be slow, and the sound continuous. Try to decrease your bow speed even further as you practise.

REPERTOIRE

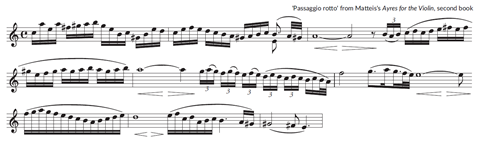

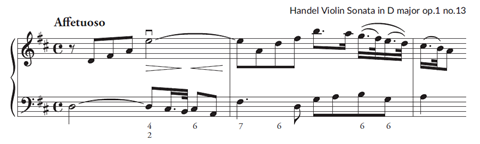

Try to play pieces that put this sort of bowing into practice, rather than repertoire that is challenging in other respects. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons concertos are very useful: the outside movements for shaping slurs of fast notes; the slow movements for shaping individual notes. You can also practise the different shapes required by playing the following examples. Focus on maintaining a good quality of sound, using your instincts to manage and balance bow speed, bow pressure and point of contact.

IN YOUR PRACTICE

In a letter written in 1760, Tartini advised his pupil Maddalena Lombardini to practise a swell on an open string using up bows and down bows for ‘at least an hour every day, though at different times, a little in the morning, and a little in the evening … beginning with the most minute softness increasing tone to its loudest degree, and diminishing it to the same point of softness with which you began, and all this in the same stroke of the bow’.

The principle is good, but I can’t imagine any student having an hour a day spare to spend on drawing slow bows! I would spend just a few minutes on the bowing exercises at the beginning of your practice, and try to bear the ideas in mind all the time while practising your repertoire.

NOTES FOR TEACHERS

I am not very systematic when it comes to teaching son filé bowing. Instead I act as a policeman: often students move the bow too quickly and I have to jump in and hold them back. Even when they use the technique correctly, it’s worth getting them to do it again for reinforcement. Sometimes students overdo the idea to begin with, but I’d much rather see that than flimsy playing. The whole point of this exercise is to push to the limit what you can get out of one bow stroke.

The most common defect in pupils’ bowing technique, in my experience, is the overuse of fast and unshaped strokes. Using a slower stroke for rhythmic emphasis in a passage of fast notes, or to enjoy a juicy harmony, is most effective, and the ability to hold back the stroke, particularly at the beginning, makes better distribution possible.

This book will give you the remedies to all your violinistic ailments. Pages 103—4 describe son filé and how to practise it, emphasising the need for sensitivity in the right-hand fingers, above all the index finger. It recommends combining the above-mentioned exercise with many slurred notes and string changes, to counter stiffness in the wrist and hand while developing sustaining power.

Robin Stowell Violin Technique and Performance Practice in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries

This book has translations of writings by Spohr, Baillot and many other non-English pedagogues writing long before Galamian. It deals withissues such as tone production and the relationship between bow pressure, speed and point of contact problem by problem, and it is certainly worth looking at.

INTERVIEW BY PAULINE HARDING

1 Readers' comment