Dmitry Badiarov, who crafted the violoncello da spalla that will make its London debut in the hands of Sigiswald Kuijken in March 2014, talks about the process of reconstructing this rare historical instrument

When Sigiswald Kuijken approached me with the idea of reconstructing a violoncello da spalla in 2003 I was on tour with La Petite Bande, the orchestra he had created and conducted for 40 years. As a violin maker who is interested in the repertoire and development of the violin from its origins, I would frequently discuss the history and evolution of the violin with Kuijken – and the possibilities in terms of reconstruction. Despite our conversations it took me by surprise when one day he asked if I would undertake a reconstruction.

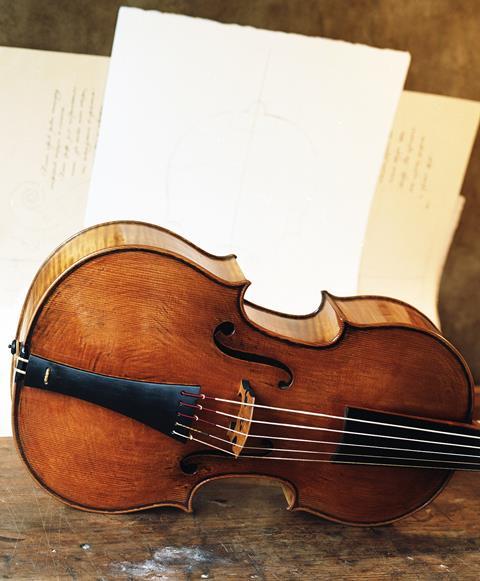

Kuijken introduced me the work of Gregory Barnett, author of the book The Violoncello da Spalla: Shouldering the Cello in the Baroque Era, published in 1998. Analysis presented by Barnett in his book, and the surviving instruments Kuijken had pointed me to, convinced me that it was possible to reconstruct one of these instruments. My reconstruction was to be based on three surviving instruments: two by J. Ch. Hoffmann, a contemporary of J. S. Bach – one of which resides in Leipzig and the other in Brussels – and one by the violin maker Aegidius Snoek, also in Brussels, made in 1708 (the photograph shows Sigiswald Kuijken holding this instrument). The two instruments in Brussels reside at the Musical Instrument Museum, and private access to these examples proved invaluable to my research during the making process.

The process of making a violoncello da spalla is similar to that of making a viola, but with a few differences. The violoncello da spalla can have up to five strings, so it is essential to make the table neither too flat nor too thin. The bodies of all three surviving instruments are 455–460mm long, with vibrating string lengths of around 428mm. The ribs are around 80mm, with the exception of the Brussels Hoffman, which was probably reduced in order to fit under one’s chin or to facilitate shifting into higher positions. The proportions of the instrument I made for Kuijken are similar to the average proportions of a viola. The neck is 30mm wide at the nut for the five-stringed versions, and its length is proportionally the same as the neck of a violin. Given the extra thickness of the strings, the neck does need a little extra width. In short, my dimensions are almost identical to those of the instruments made by Hoffman in the 1720s.

While Kuijken and I worked on the model, figuring out which features of which instruments were most likely to be original and in common use in the 18th century, Mimmo Peruffo of Aquila Strings, a leading string researcher, worked on a prototype of a historical gut string. We needed concert quality strings that would emit a cello pitch at a vibrating length of 428–430mm, and Peruffo had a strong idea of how this could be achieved. I also asked several non-gut string makers, and in 2012 Franz Klanner of Thomastic came up with some superb synthetic strings that now adorn the instrument made for the brilliant virtuoso Sergey Malov.

Playing a violoncello da spalla is more comfortable than one might imagine. The instrument is suspended on a thick leather belt, so there is no need to support its weight with the left arm. The left hand position is different to that used to play a violin: players of the violoncello da spalla stretch their first finger more often than their small finger, and ‘roll’ their palm in order to minimise the strain in stretchy passages or chords. This is a common practice with cellists and plucked instrument players.

Over 40 surviving instruments are listed in the article I wrote for the Galpin Society Journal in 2006, entitled The Violoncello, Viola da Spalla and Viola Pomposa in Theory and Practice. The majority of these were either rebuilt as cellos for children or made into violas. These instruments are usually classified as cellos or viola pomposa – the enigmatic instrument that legend tells us was invented by Bach but which was in fact not, as the majority of scholars agree.

What Sigiswald Kuijken and I have reconstructed is the instrument that in the late 17th century and the first half of the 18th century was commonly called a violoncello, and which apparently vanished in the second half of the 18th century. Now it has returned, and is drawing the attention of music lovers who are thirsty for adventure.

Dmitry Badiarov is a violinist and violin maker with a specialist interest in the history, construction and performance of historical instruments, among them the violoncello piccolo da spalla, violoncello, viola da spalla, viola pomposa.

Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial.

No comments yet