Makers of chin rests and tailpieces have adopted new and exciting materials in recent years, with interesting implications not only for weight and strength, but also for the instrument’s tonal capabilities. Peter Somerford investigates

Recent directions in tailpiece construction have seen makers turn from traditional hardwoods such as ebony and rosewood to high-tech materials including carbon fibre, titanium and aircraft alloys. Such choices are based not just on the material’s physical properties, such as weight, strength and stiffness, but also on its acoustic attributes. Chin rest makers have also sought out lightweight, strong materials including composites, alloys for mounting systems, and titanium for clamping screws. With both types of accessories, one of the major acoustic goals is to avoid unwanted damping effects. While designers of both accessories need to consider aesthetics and functionality alongside sound, chin rest makers additionally have to think about player biomechanics and factors such as skin reactivity.

Kenneth Kuo’s carbon-fibre Tonal Tailpiece and Frirsz Music’s alloy tailpiece are two examples of high-tech engineering that aim to maximise the sonic potential of an instrument. For cellist and inventor Kuo, carbon fibre’s stiffness is more fundamental than its low weight when seeking to retain as much vibration as possible. ‘My most important discovery is that lighter is not always better,’ he says. ‘Carbon-fibre tailpieces can be extremely light, but the crucial factor in making the instrument vibrate more is not the weight but how dense the tailpiece is.’ Each Tonal Tailpiece is individually handmade from layers of carbon fibre and resin, so no two are identical, and Kuo is able to tailor the stiffness and weight to the player’s needs and sound preferences. ‘Before I make a tailpiece,’ he says, ‘I ask the player for dimensions of the instrument’s length and bottom width, and I ask about the characteristics of the instrument, its response, and whether a player wants more bass or wants the sound to cut through more.’

Kuo recently developed a 25mm-longer Generation 2 model for larger cellos. His initial motivation was to avoid an awkward-looking excess of tailgut between the tailpiece and the saddle, but he found that on his own Francesco Gofriller cello, the Generation 2 gave him the benefit of a much deeper sound. ‘The instrument is 767mm long but the ribs are incredibly narrow,’ he says, ‘so it wasn’t giving me the warmth and earth-shaking low end – until I put on the Generation 2.’ Kuo acknowledges that there are limits on what cellists can do to increase the projection and volume of their instrument, but says that one of the benefits of the Tonal Tailpiece is its response. ‘A side effect of having something so dense and light is that it makes you play faster. Ultimately, there is no perfect sound, so you have to ask yourself: “Can the tailpiece make you play better? Do you trust it to give you that extra little edge?”’

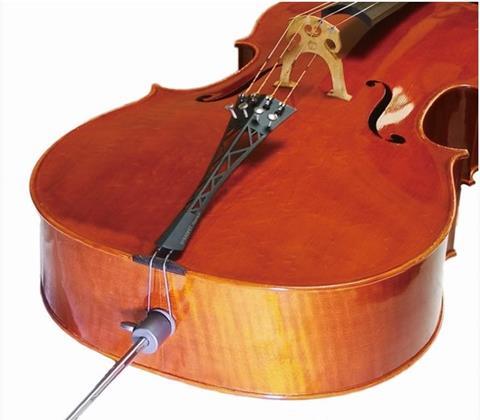

Violin maker and inventor Nicholas Frirsz’s alloy tailpiece evolved after 30 years of experimenting with various metals, plastics and composites. Alongside the cut-out designs of his cello tailpiece and Ultra violin and viola models, Frirsz offers versions for violin and viola in solid alloy and wood, and is currently redesigning his significantly more affordable composite tailpiece, the Acousticon. ‘The wooden tailpieces have their place,’ says Frirsz, ‘but for bringing out the overtones, resonance and quality of the instrument, the aerospace alloy models have a more pronounced effect.’ He adds that the cut-out design of the Ultra models was not driven so much by weight considerations as by how the sound is balanced harmonically. ‘It’s already a light tailpiece, so the cut-outs are more for the harmonics and overtones, and for opening up the possibilities for the instrument.’

The Frirsz tailpiece is distinguished by its asymmetric, harp shape, with the after-length progressively increasing from the highest-pitched string to the lowest-pitched string. The tailpiece also incorporates a ‘twist’ where the strings attach. These two design elements each balance out different forces, says Frirsz: ‘The progressive after-length equalises the pulling tension of the strings, while the twist balances the asymmetric forces of the strings pushing down on the bridge.’ Frirsz claims the combination of material and design can produce more response, projection, balance and clarity from an instrument, but he acknowledges that a player’s impression of sonic improvements is very individual. ‘Everybody interprets and perceives such effects differently, but the tailpiece definitely makes a change. And for cellists, one of the side-benefits is a reduction in wolf notes. Instead of having to add a wolf eliminator that dampens the sound, with this tailpiece cellists can suppress the wolf without muting the bottom strings.’

Chinese manufacturer Stradpet specialises in accessories made from titanium, which it chose for both its physical and acoustic qualities. The Grade 5 titanium alloy it uses for its tailpieces includes a small percentage of aluminium and vanadium, which makes it harder and stronger than pure titanium, in addition to being lightweight and resistant to corrosion. Compared with steel, titanium alloy has faster sound transmission and increased resonance, notes Stradpet founder and chief engineer Li La, who in the course of the product development process tested titanium tailpieces of different weights, thicknesses and design (both solid and cut-out variations), comparing them with each other and also with wooden tailpieces. The tailpieces were tested by players and evaluated by listeners, and Beijing violin maker An Zhang ran acoustic tests using equipment developed by US maker Joseph Curtin. ‘The feedback from players was that compared with a wooden tailpiece, the titanium one was more sensitive and produced a louder, richer and clearer sound,’ says Li La. ‘Audience feedback confirmed this impression, and the acoustic tests showed improved response at critical frequency bands compared with the wooden tailpiece.’

Like Kuo, Li La says that lighter is not always better. When comparing four different titanium violin tailpieces, ranging in weight from 8.5g to 17.8g, he found that the lightest tailpiece lacked richness and definition. ‘The heaviest one had a rich tone and good bass, but the 10.6g tailpiece had more sensitivity and a clearer sound. That’s why we aim to have the weight of our tailpieces near the middle of the range.’ Using computer-controlled cut-out designs allows Stradpet precise control of the weight of the tailpiece.

The tailpieces from the above-mentioned makers are nearly all premium models, where high-tech materials and design innovation come at a price. Other makers specialise in more accessible alternatives to traditional wooden tailpieces. German manufacturer Wittner produces light-alloy models but uses a composite for its Ultra range of tailpieces. ‘We wanted a material that was environmentally sustainable, but weight was always going to be a big factor,’ says the company’s CEO, Horst Wittner. ‘We tried many different materials until we found a composite that was sufficiently light, strong and stable, and had a good sound. The light-alloy model is about 20 per cent heavier than the Ultra, which I would consider a disadvantage. But we have some customers, especially jazz players, who want a more brittle or metallic sound, so they feel the alloy meets their needs better. There is always a range of opinions and personal feelings about sound.’

Player perceptions of a new chin rest may be coloured less by changes to the sound than by how well the chin rest fits with their physiology, biomechanics, and preferred playing position. But chin rest makers, at the same time as offering a range of shapes and styles and incorporating adjustments in height and tilt to accommodate different needs and preferences, have also focused on aspects that can have an influence on the instrument sound and might contribute a damping effect. Such aspects include the weight of the chin rest, where and how it is clamped, and how the clamping pressure is distributed.

Recent chin rest models by Wittner, Swiss start-up Dolfinos and Slovenia-based Viva La Musica (VLM) use different materials and clamping structures, but have one thing in common: they are all centrally mounted, over the bottom-block. Dolfinos’s founder Michael Wiener says: ‘The most important influence of a clamping system on the instrument, in terms of acoustic effects and also in preserving the value of the instrument body, is placement. We worked with acoustics expert Jim Woodhouse at Cambridge University to determine where best to hang the chin rest system to achieve the least disturbance materially and acoustically, and that place is the bottom-block.’ Dolfinos’s chin rest system comprises an adapter made from aircraft alloy, which is mounted directly on the instrument, and into which is fitted an ergonomic chin rest of the player’s preferred shape and style, made from a choice of different woods or antistatic ABS.

Wittner’s Zuerich chin rest is an over-the-tailpiece design that has the cup sitting on the left side. With adjustable height and tilt, the Zuerich form is designed to give players flexibility in their playing position, with the ability to switch between central and lateral contact points while playing. VLM Augustin’s new Super Adjustable chin rest sits over the bottom-block but the plate of the chin rest can be moved to the left by up to 15mm, in addition to being height- and tilt-adjustable.

When considering the chin rest material, makers factor in not just weight, and how that might affect the sound, but also how the chin rest contact surfaces react with the skin. VLM Augustin chose a lightweight, hypoallergenic plastic for the chin rest plate, and titanium screws, which designer Augustin Penic says are not just extremely light – ‘the more material you put on the violin, the less the instrument vibrates,’ he reasons – but sound better than nickel and come without the associated allergic reactions that some players experience.

Wittner uses a lightweight, anti-allergic composite material for the plate and the clamps. Horst Hildebrandt, a professor of music physiology at the Zurich University of the Arts who collaborated with Wittner on the development of the Zuerich model, says: ‘For a top-class instrument with a perfect overtone spectrum, you don’t want any damping or muffling of the sound. Therefore the ideal chin rest is a light, dense and stable structure that doesn’t disturb the acoustic qualities of the instrument and doesn’t invite players to press or clamp instinctively with their head and shoulder, which might cause additional damping effects. Players appreciate both the flexibility of the Zuerich form and the low weight in comparison to wooden chin rests, with most players judging the sound to be more free because overtones are not damped.’

Whereas Wittner and VLM Augustin use a more conventional two-leg clamping approach, Dolfinos’s adapter features a specially developed clamping system. Wiener says: ‘Traditional clamping systems add peak pressure points in delicate areas on both sides of the instrument, whereas our clamping system better distributes the energy of the clamping force across the entire surface where cork touches the instrument. This technology protects the value of the instrument body, and in terms of the system’s acoustic benefits, players almost always report that their instrument rings more and has a fuller sound, with better harmonics and fewer wolf tones.’

For all a chin rest’s potential acoustic qualities, Penic believes it’s more important that the chin rest allows the musician to play freely, with a relaxed posture and no pain. He says: ‘If I could choose between a chin rest that’s better for sound and one that’s better for the body, I would pick the latter, because I will feel better and play better.’

While many players look for the perfect balance between chin rest and shoulder rest, others prefer not to use a shoulder rest at all. Depending on a player’s physiology and neck length, the Dolfinos, Wittner and VLM Augustin chin rests all allow for playing without a shoulder rest, but another chin rest solution actively encourages this. The Chinrest Lip, developed by violinist Peter Kaman, is a small block of foam rubber that the player affixes to an existing chin rest. Kaman explains: ‘The Chinrest Lip helps you feel more secure holding your instrument without a shoulder rest. The lip acts as a fulcrum, so when your chin goes over the lip, the natural weight of the head, supported by the collarbone, raises the scroll.’ He claims that it’s easier to produce a full-bodied tone without a shoulder rest, because the player’s bow arm and bowing action don’t have to compensate for the raised string height that can result from using a shoulder rest. He adds: ‘When you play without a shoulder rest, you can feel the vibrations of the instrument on your body. The sound is better, because there’s nothing getting in the way. With a shoulder rest, you have these two clamps on the instrument, which to some degree attenuates the instrument vibrations. Playing without a shoulder rest helps to let the violin sing more.’

As with most accessories, no single chin rest or tailpiece will be the best solution for every player. That is why inventors continue to tweak and improve their designs. Kuo, for example, is exploring the idea of a flat rather than curved tailpiece, after hearing about experiments with such a design at a past

VSA/Oberlin workshop. Frirsz is adding extra stability to his Acousticon model and also experimenting with different tailgut materials. And chin rest manufacturers including Wittner are exploring how they can adapt existing models to cater for extreme biomechanics, individual anatomies and injuries, without compromising the sound.

-

This article was published in the June 2021 Bomsori issue

The Korean violinist on graduating from the competition circuit to become an international soloist - and why singing is at the heart of her playing. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Korean violinist Bomsori

- The Knopf bow making dynasty

- Violinist Joseph White’s 1875 New York debut

- Sitkovetsky Trio on recording Ravel

- Master copyist Vincenzo Postiglione

- London-based string group the 12 Ensemble

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet