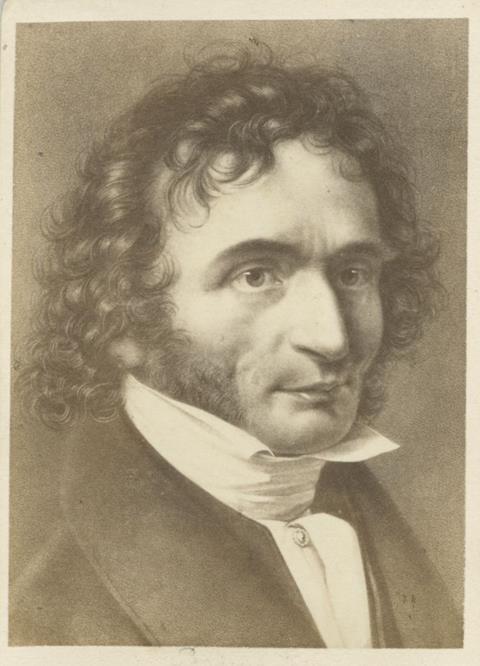

The great virtuoso’s greed and gambling addiction almost cost him his fortune. Stewart Pollens tells the story of bad business and legal hot water

The last years of Nicolò Paganini’s life, up until his death in Nice in 1840, were marked by increased physical disability and discomfort due to the progression of his long-standing illnesses (possibly syphilis, tuberculosis, rheumatism, or a combination of the three), which required him to retreat from the concert stage. He was also beset by a series of professional disappointments, including a failed attempt to become the director of the court orchestra in Parma, Italy.

In 1837 he made what turned out to be an unwise investment in a casino (a term that at that time referred not exclusively to a gambling establishment, but also to a venue for public meetings, concerts and dancing). The establishment, however, went bankrupt within a few short months and embroiled Paganini in court battles that occupied his attention until the day he died.

At the height of his spectacular career, Paganini reputedly earnt a great deal of money, particularly for his tours of Vienna, Prague, Warsaw, Berlin, Leipzig, Paris and London. In the 1831 concerts he played in London, for example, his combined fees purportedly exceeded £10,000, an enormous sum in those days. The French press characterised him as a millionaire even though he often donated his fees to charity, and the few occasions when he declined to play at fund-raising benefits earnt him a reputation as a miser.

Paganini was addicted to gambling. He admitted: ‘I often lost in one evening the fruit of several concerts’

Although he lived abstemiously while on tour (preferring to stay at roadside inns rather than in better-appointed city hotels), he was addicted to gambling. In one autobiographical sketch, quoted in de Courcy’s biography of Paganini, the violinist admitted: ‘I often lost in one evening the fruit of several concerts and not infrequently saw myself in difficulties from which only my art was again able to extricate me.’ In 1837 he made out a new will naming his recently legitimised son Achille as his executor, who was to administer two trusts totalling 125,000 lire, the interest from which was to go to two of Paganini’s sisters.

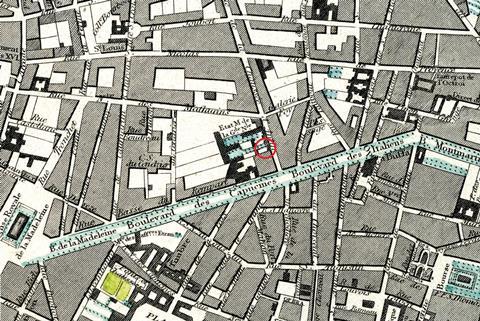

In 1835 an old friend and occasional secretary of Paganini’s named Lazzaro Rebizzo began making plans with several entrepreneurs to open a casino in Paris. Rebizzo contacted Paganini and invited him to become a co-investor and music director. Paganini hoped that its concert hall would, in his words, ‘cater to the cultured classes and embrace all the arts’.

According to the original plan, the casino would include ‘a clubhouse, a hall for balls and concerts, a library, a museum and an atelier for the publication of literary and musical works’. However, it evolved into a flamboyant establishment that had, in de Courcy’s description, ‘billiard and gaming rooms, as well as a retiring room, or boudoir, padded in flannel for the artists’.

The casino was located in a converted residence in a fashionable district of Paris, and an apartment was set up in it for Paganini. The name of the establishment, Casino Paganini, was emblazoned in gold letters two feet high.

Paganini’s biographers have not always been kind: he has been portrayed as vain, desirous of flattery, megalomaniacal, ambitious, avaricious, miserly and as a libertine – traits that may have played a part in his decision to become involved in what was hoped would be a highly lucrative investment. On the other hand, he may have viewed this venture as an opportunity to achieve a lifelong ambition to direct a dignified musical ensemble, as well as to enjoy a more stable lifestyle than that of a travelling virtuoso.

Whatever Paganini’s expectations, however, they were quickly dashed. The first crises were the denial of a gambling licence to the casino, and the arrival in Paris of Johann Strauss and his orchestra for a three-week residency, which forced the casino directors to postpone its opening concert for fear of poor attendance. The inaugural event finally took place on 25 November 1837, though Paganini did not perform – he made a brief appearance but was too ill to attend all of the opening festivities.

Paganini’s casino had billiard and gaming rooms, and a flannel-padded boudoir for the performers

Instead, Cesare Pugni, who had been engaged as the orchestra’s violinist–conductor, presided. This inaugural concert was evidently not an overwhelming success, so the casino directors arranged for Paganini to perform at a later date, expecting him to draw his customary crowd. His concert was well advertised, but again, he was too ill to perform on the day and had to withdraw, forcing the directors to engage the Paris Opera chorus at the last minute. Unfortunately, the casino’s operating licence did not cover this kind of performance, and as a result the authorities shut down the casino on 31 January, just two months after it had opened.

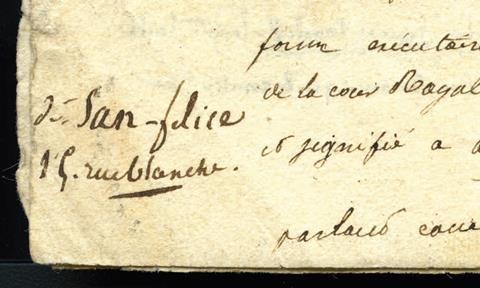

The casino’s final concert, which took place the day before its official closure, featured a singer, one Dame San-Felice, who had signed a contract with the establishment’s owners that guaranteed her an annual salary of 9,000 francs. Since the casino was being shut down by the authorities, she realised that it would be in breach of contract and that she would not receive her full year’s salary, so she proceeded to sue the casino for its entire receipts. This contributed to the owners’ decision to liquidate the corporation.

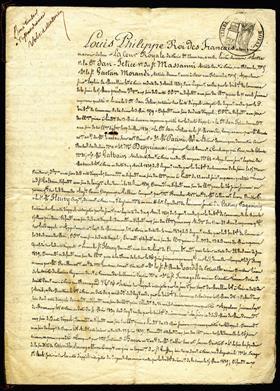

A decree issued by the Royal Court of Paris, Second Chamber, registered in Paris on 19 July 1839, recounts and summarises the sequence of court decisions relating to the liquidation and bankruptcy of Casino Paganini, as well as an appeal lodged by five creditors, including the singer San- Felice. On 12 May 1838 the Casino Paganini Corporation (which is also referred to in the court proceedings as de Petinville, Fumagalli & Co.) was dissolved – a voluntary procedure in which a nominee curtails a corporation’s activities and pays off its creditors.

For some unknown reason, Ambrogio Fumagalli (the nominee in charge of the liquidation) halted payments to several of the creditors, which led the Commercial Court of the Seine to initiate bankruptcy proceedings, ultimately declaring the corporation bankrupt on 12 June 1838. However, on 15 March 1839, the court reversed this decision and returned the matter to liquidation. Five creditors were dissatisfied with this reversal and appealed to a higher court, the Royal Court, and on 3 May 1839 it overthrew the Commercial Court’s decision and reinstated bankruptcy proceedings.

On 3 June 1839 the court ruled that San-Felice was to be awarded 6,000 francs; a Monsieur Pacini (a composer who had supplied compositions to be played at the casino) was to be awarded 3,075 francs; and a Monsieur Despreaux (a merchant who had supplied velvet – perhaps to upholster the boudoir) was to be awarded 520 francs. Upon appeal, Pacini’s award was reduced to 1,000 francs and San-Felice’s to 3,280 francs, and in addition she was fined 50 francs as a penalty for lodging her final appeal. A handwritten copy of the court summary was prepared and delivered to her for an additional charge of 50 centimes. Her name and address, 19 rue Blanche, is written on the lower left-hand corner of the last page of this document.

As revealed in the text of the court proceedings cited above, translated by Francis Ackerman, no action was taken against Paganini himself, and his name in fact only appears in passing: ‘It has been alleged that Dame San-Felice ceased to be a creditor of the Fumagalli and de Petinville Corporation as a result of a transaction whereby she transferred her rights to Sr. Paganini.

‘Given that the document in question, always supposing that it exists, could not bind the corporation against Paganini, except to the extent the latter had given notice in due form, and that no representation has been made concerning any document, notarised or otherwise, signed by Paganini, from which it could be inferred that the latter had appeared in the guise of attorney in-fact for Dame San-Felice, the exception raised by Fleury must be viewed as unjustified and groundless.’

However, another lawsuit was lodged against Paganini himself, charging him with failing to fulfil his responsibilities as musical director, conductor and player. The casino’s directors sought 10,000 francs for each instance in which they alleged he had failed to perform his required duties, totalling 100,000 francs. All of this was played out in the Paris newspapers, and Paganini defended himself against these charges in a letter to the editor of Le droit published on 23 March 1838.

In it, he denied that he had been obligated to conduct the casino’s orchestra or that he had been contracted to play on a weekly basis. He cited his subsequent confinement in a sanatorium as proof of illness and as a legitimate excuse for failing to satisfy any implied obligations. He also pointed out that of the 64 shares initially issued by the casino corporation, he had purchased 60 for a sum of 60,000 francs, and therefore it was he who had lost the most in this ‘abandoned enterprise’, as he referred to it.

To add insult to injury, Lazzaro Rebizzo (who had involved Paganini in the first place), demanded compensation from the violinist to the tune of 30,000 francs, the amount that Paganini had initially put up on his behalf.

The Royal Court in Paris ruled against Paganini on 2 March 1839, and demanded that he pay damages of 20,000 francs, which was subsequently increased to 50,000 francs in January 1840 following his appeal. On 17 April 1840 the French vice-consul arrived at Paganini’s residence in Nice in an attempt to collect the funds, but the violinist referred him to his lawyer in Genoa.

Paganini’s financial situation at that time is unclear. On the one hand, it seems as though funds were in short supply. In February 1839 Paganini’s lawyer in Genoa, Luigi Guglielmo Germi, had to borrow money from a Genoese bank on the violinist’s behalf to cover legal expenses incurred in the casino suits, and he subsequently informed Paganini’s banker there, Luigi Bartolomeo Migone, that his client intended to sell some of his belongings to repay the loan. The banker wrote back confirming that Paganini had also been borrowing money himself.

However, on 11 June 1838 Paganini had made a very generous and unexpected gift of 20,000 francs to the young Hector Berlioz, which suggests that he had other funds at his disposal.

One of Paganini’s money-making sidelines at this time was violin dealing. On 20 March 1839, according to de Courcy, he wrote to the violinist Vincenzo Merighi:

‘I’m glad to have the beautiful cello, which I always keep with me along with the Stradivari violin, which completes the quartet. This inspires me with the desire to buy some beautiful instruments with the purpose of reselling them, given the likely possibility of a demand for them. Therefore, since you so kindly offer to do so, try to get me some Stradivari cellos, violins and violas; but at a price that will leave a margin for a turnover when reselling them. There is little demand for Amati violins, but get some by Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. The instruments must be in perfect condition and of good, strong wood. It is only fair that I divide any profit with you, to repay you for your pains and kind efforts on my behalf… For God’s sake, don’t talk to me of repaired violins with visible cracks, but negotiate for good violins, of strong wood that hasn’t yielded at the bridge. And let’s leave all the other defective instruments to the dealers… Therefore, try to get me the most beautiful Stradivari and Guarneri cellos, violas and violins… since I want to succeed as a dealer in stringed instruments. But you shouldn’t let anyone know about it because if they hear that Paganini wants to buy them they’ll charge exorbitant prices’.

With the French courts pursuing the 50,000 franc fine that they had imposed upon him, Paganini was fearful that the authorities might sequester his violins, which he had been storing in Marseilles with his friend Camille Brun. On 17 January 1840 he wrote to his lawyer, Luigi Guglielmo Germi:

‘As regards those rascally thieves or pirates in Paris, could they possibly sequester the instruments that are at M. Brun’s in Marseilles? Think about the matter seriously and we’ll write to the latter. In case he can’t guarantee [their safety], let us write to Signor Borelli [the nephew of Paganini’s banker in Genoa] to find a way to remove the instruments and prove that they belonged to me but now belong to him, I having sold them to him. He should suggest to me some way to save a not inconsiderable capital. There are eleven violins, one viola and four cellos – all at fancy prices. Count de Cessole doesn’t want to pay me more than 4,000 francs for the Stradivari violin, and I’ve agreed to it, seeing that it is rather small.’

In conclusion, Casino Paganini turned out to be a major fiasco: Paganini not only lost his investment capital, but also had to pay the considerable cost of his legal representation in the courts. Even as he lay dying, this matter remained a major annoyance. After he died on 27 May 1840, it is not known whether he or his son and executor, Achille, ever paid the fine levied on him, or reached a settlement with Paganini’s old friend Rebizzo.

This article was first published in the December 2011 issue of The Strad

No comments yet