Cellist Jan Vogler’s latest cross-arts collaboration has transported him into an exciting new realm. He talks to Pauline Harding about great American literature, music spanning three centuries, and a chance encounter that brought Hollywood star Bill Murray on to his stage

It’s 11am on a Sunday in June and I’m at the Dresden Music Festival, in the Kulturpalast, waiting for a concert to begin. Cellist Jan Vogler (the festival’s artistic director), violinist Mira Wang (his wife) and pianist Vanessa Perez are due to perform music with an unusual twist: it will be interwoven with readings by Hollywood actor Bill Murray. They are late. After some time the audience claps hopefully. Nothing. Are we to be subjected to the rock-star behaviour of the rich and famous, I wonder – will we be left sitting in suspense for hours? Will they turn up at all?

As I prepare myself for the worst, we are plunged into darkness. A voice booms down from a PA system, resonating in the hall’s clear acoustic like a message from God. ‘This is Jan Vogler,’ comes a suspiciously American drawl that most definitely sounds like Murray. ‘Now, everyone needs to know that you’d better turn your phones off, because Bill Murray is a crazy psychopath and if he hears any phones ringing during the performance, he’ll run into the audience to answer them. OK?’ A spotlight beam flashes on to an empty chair, then the piano. Now the entrance at the back of the stage lights up, and out of the yellow glow step Wang, Perez and Murray. The concert hall is packed and the excited audience thunders with applause.

Murray, sombre, begins by reading part of a 1958 interview with author Ernest Hemingway: ‘I used to play cello. My mother […] thought I had ability, but I was absolutely without talent. We played chamber music – someone came in to play the violin; my sister played the viola, and mother the piano. That cello – I played it worse than anyone on earth.’ At this point Vogler enters, sits down rather apologetically with his 1707 ‘Fau, Castelbarco’ Stradivari cello (see box, page 33), and performs the Prelude from Bach’s G minor Suite. Despite the ominous introduction, he plays beautifully, with something remarkably unpretentious and childlike in his demeanour and sound. It is difficult not to lean with him as he phrases, or to be moved by the rivulets of joy that flow from his bow. His connection with both music and audience is tangible.

What follows has the potential to be disjointed: a reading of Hemingway, Walt Whitman or James Fenimore Cooper here; a movement of Ravel, Piazzolla or Gershwin there. But it is not. As Murray reads from Whitman’s poem cycle Leaves of Grass (1855) and Cooper’s novel The Deerslayer (1841), the musicians perform the slow movement from Schubert’s B flat major Piano Trio. His voice winds its way into music performed with shiver-inducing subtlety. As the movement fades to a close, the reading also reaches its end, leaving the audience spellbound in haunted silence. So the concert is set to continue. So how did a German cellist and a Hollywood star come to join hands? American actor, comedian and writer Murray needs little introduction, having garnered awards for his roles in Ghostbusters, Rushmore and Lost in Translation. He is also a great poetry enthusiast: in 1995 he was introduced to the New York poetry society Poets House by his neighbour Frank Platt, a founding board member; Murray helped to fund the cataloguing of the Poets House library, and this year received the society’s Elizabeth Kray Award for his services to the art form. Almost every year Murray attends Poets House’s annual fund-raiser poetry walks across the Brooklyn Bridge; there he has performed readings alongside Billy Collins (US Poet Laureate 2001–3), Sharon Olds (Pulitzer Prize in Poetry 2013) and more – including of works by Whitman. Last year he invited Vogler along to the walk, when no doubt ideas of a collaboration began to sprout.

‘I longed to know a great painter, a fantastic dancer – people who could inspire me on different levels’

Vogler is, of course, a highly successful performer in his own right: he has premiered major new works including, in 2010, Tigran Mansurian’s Cello Concerto with the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln and Semyon Bychkov in Cologne, Germany and, in 2015, Wolfgang Rihm’s Duo Concerto for violin and cello, with Wang and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in New York. He has also performed as a soloist with orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Staatskapelle Dresden, Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra and many more, and gives recitals with pianist Hélène Grimaud. He records for Sony Classical, with his latest CD (2016) featuring pieces by Tchaikovsky, and his recording of the Bach Suites winning an Echo Klassik Instrumentalist of the Year Award in 2014. He has been artistic director of the Dresden Music Festival since 2008 and of the nearby Moritzburg Festival since 2001; he received the European Award for Culture in 2006; and in 2011 he was presented with the Erich Kästner Prize for tolerance, humanity and international understanding.

But above all, Vogler is a man who likes to share ideas and think outside the box – and that is what he did in 2013 when he found himself sitting next to Bill Murray on a flight from Berlin to New York. ‘We really hit it off,’ says Vogler. ‘After that Mira and I would go to his parties and movie premieres, and he came to my concerts. He always said this project was my idea, but I think it was his. He planted it in my head!’

Perhaps, though, the project came from somewhere deeper in Vogler’s psyche. Born in 1964 in East Berlin, he grew up in artistic isolation on the ‘wrong side’ of the Berlin Wall, where he initially studied cello with his father, Peter Vogler, and later Josef Schwab, Siegfried Palm and Heinrich Schiff, who died earlier this year. Vogler remembers Schiff as a great teacher with an approach that was ‘intelligent, but not academic’, with inspiring energy and taste. In 1984, aged 20, Vogler became the youngest ever principal cellist of the Staatskapelle Dresden. As a result of all this discipline, a yearning had taken hold: as a teenager Vogler would sneak into a small theatre near his East Berlin home and dream of making friends in worlds other than his own. ‘I grew up in a family of musicians,’ he says. ‘My parents would tell me how much you have to focus to become a classical cellist, to be truly, deeply in your field. But I always longed to know a great painter, a fantastic dancer – people who could inspire me on different levels.’ In 1989, when the Wall came down, artistic limitations fell with it. ‘I was 25 and suddenly I had friends in America and West Germany, and I did meet painters and dancers,’ says Vogler. ‘The Leipzig school of cello playing was strong in East Germany, so I grew up with a particular type of sound production, technique and style. Bach’s Suites and Beethoven’s sonatas were “God pieces” – you had to kneel down and obey the score. When I saw other art forms later, I felt I could loosen up: it put things in perspective. I realised that yes, it’s important how you play that one note, but it’s not going to get you to understand the piece as a whole. Suddenly I could see the world, and my life became more colourful.’

Marlboro Music Festival was particularly important: there he met new colleagues including violinists Joshua Bell, Pamela Frank, Christian Tetzlaff – and Wang, his wife. Although he kept his position as principal cellist of the Staatskapelle Dresden until 1997, when he moved to New York to pursue a solo career, he decided to bring inspiration closer to home by co-founding the Moritzburg Festival in 1993. This would never have been permitted in the area before. ‘In East Germany, to found a festival would have been anarchy!’ he says. ‘Moritzburg was very much in the spirit of a new freedom. I invited people who I thought were incredibly interesting, from different schools of playing: Heinrich Schiff; Sol Gabetta; Janine Jansen. It was an attempt to say, “Come here, great friends and colleagues, and let’s inspire each other.” In classical music we are trained to go to a door we know and bang very hard on it. Even if it doesn’t open, we keep banging, when instead we should see which other doors will open. Yes, there’s a risk that what we find will disappoint us; but we might come to a new world that’s very interesting – like Alice in Wonderland.’

Despite Vogler’s longing to break away from norms, his formal upbringing has given him a strong foundation from which to explore and connect with other worlds. Overall, this year’s Dresden Festival was exceptionally eclectic: we were treated to everything from Gil Shaham performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto; to a performance of choir, orchestra, electronics and cinema; to a classical organ recital by pseudo-punk Cameron Carpenter, who gave a virtuosic, near-deafening display on a homemade organ in a warehouse lit with pink and blue lights. To put their programme together for the Dresden concert, Murray, Vogler and friends met at each other’s houses to discuss first music and later literature; they bought bagfuls of books to pore through and read for hours. ‘I made a music list: Gershwin, Bernstein, Stephen Foster,’ says Vogler. ‘I thought Piazzolla would be great: he was a New Yorker with a South American connection, who studied in Paris. La muerte del ángel goes well with Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast (1964), because they’re both so outrageous and sexy – the Hemingway is all about Paris life in the 20s, with all the painters, prostitutes and everybody together in one pot.’ When they found a love scene in Truman Capote’s novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958) which they felt needed musical support, Murray was still pressing an exhausted Vogler for ideas at 2am, until he came up with Elgar’s Salut d’amour. ‘He just squeezes ideas out of me!’ says Vogler. ‘It’s inspiring.’

For Vogler, Schubert’s roots run deepest: when he was a child his father played recordings in the car that contributed to his thoughts about music, nature and poetry. ‘We would drive in the countryside on a rainy day in the winter and listen to his string quartets, the quintets, Dichterliebe,’ says Vogler. ‘It was unbelievable how much Schubert describes nature.’ It was Jim Downey, a writer on TV show Saturday Night Live, who suggested including Cooper here. ‘The deerslayer stands on top of a mountain and is in awe of the religious dimension of nature, of its untouched quality,’ Vogler explains. ‘Magic happened, when we put the Schubert underneath. It really fits. I know every word now, and each time I hear it I discover new nuances in the text. And recently I found out something interesting. What did Schubert read on his deathbed? Cooper!’

‘We should see which other doors will open – we might come to a new world that’s very interesting’

So, Vogler concludes, perhaps Schubert’s music was inspired on some level by Cooper’s writing about nature; and looking at different contemporaneous art forms can spark new ideas across the board. ‘It helps us to understand the world we are in with each piece,’ Vogler says, so carried away in his enthusiasm that he puts his glasses on upside down before setting them right again. ‘If you understand that the Schubert B flat major Trio describes nature, you will still do the right dynamics and accents; but you will get a different feeling for it. Suddenly the music carries itself.’

This is a realisation that Vogler has taken into his ‘normal’ work: most recently, performances of Britten’s Cello Symphony with the CBSO. ‘The Britten doesn’t have as wide an audience as the Bill Murray project, and yet they feed off each other,’ he says. ‘Now that I’m looking more closely at history, I can understand more who Britten was, when he lived. He wasn’t just an elegant, educated British gentleman with a flamboyant lifestyle. He lived through the first and second world wars – and imagine being gay at that time. This piece has all that emotion and experience in it.’ He cites the nervous, flighty second movement; the beautiful third; a cadenza that speaks of catastrophe and disharmony; and the final passacaglia, which twists the work into an optimistic end. ‘It’s a thorny piece for most listeners,’ he says, ‘but if your audience trusts you, sometimes you can take them with you. It’s like in the Whitman poem, Song of the Open Road, when he says, “Whoever you are, come travel with me. Travelling with me you will find what never tires.” That’s what I hope to do here.’

There have been other important lessons to learn from combining music with text: ‘Bill is a master of timing, as all great artists are,’ says Vogler. ‘It’s almost like a good jazz beat: he’s right there, relaxed, but he never drags. He is always in the moment, and to do that is not easy for classical musicians, when we have played a piece a thousand times and we know how it goes. We tend to review what’s happened and to look ahead during a performance. Bill’s helped me to let go a little bit – to be precise and responsible for my art, but to let the aeroplane fly.’It is timing, too, that makes Murray such a powerful singer. In the concert, the foursome began Gershwin’s It Ain’t Necessarily So as a trio, with Murray joining in to sing in character with a shamelessly strong American accent, before leading the audience through the chorus: ‘It ain’t necessarily so, it ain’t necessarily so,’ we sang. ‘The things that you’re liable to read in the Bible – it ain’t necessarily so.’ More followed, including Foster’s Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, sung as a characterful ode to memory. Love and wistfulness were achingly present in the performers’ expressions, demeanour and sound; at times the air was so poignant, so sad, that it was impossible to guess how anything could follow.

In part, what made the performance so effective was its expressive range: from dry beginnings it spiralled into bursts of sorrow and happiness, pulling the audience with it. In Bernstein’s ‘Somewhere’ and ‘I Feel Pretty’, Murray sang with gusto, and span around and flapped his wrists with enchanting charisma. He is a master of contrast – something important for classical musicians too: ‘If you start the Schumann Cello Concerto too loudly, with too much vibrato, it’s already dead,’ says Vogler. ‘You have to start simply, and then you have a long way to go. It’s a lesson we learn after doing many concerts, when we think, “But I played so well, why didn’t the audience go totally wild?” It’s because the range of expression wasn’t so great.’

Bill’s helped me to let go a little bit – to be precise and responsible for my art, but to let the aeroplane fly

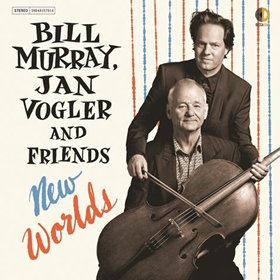

Working in the recording studio helped them to develop the programme with this in mind. (The CD, entitled New Worlds, will be released by Decca Gold in September.) ‘We would do something twice or so, and very quickly we would feel what was needed,’ says Vogler. They added Van Morrison in March – Murray had the idea when he was driving through the desert in California at sunset, listening to When Will I Ever Learn to Live in God. Vogler was enthusiastic, particularly because he wanted to play the Hammond organ solo on his cello. It was obvious just how much they enjoyed all of the performance, but this was a high point: Murray sang with all of his acting skills behind him, his initial reserve building to such a controlled, then unleashed, climax, with the piano trio standing and playing at full pelt, that the audience whistled, stamped and applauded with glee.

Vogler, Murray and their colleagues plan to tweak the programme on an ongoing basis – for a world tour beginning this autumn that will encompass Australia, New Zealand, the US, the UK, Switzerland, France and elsewhere – to keep their inspiration alive. ‘We want to bring in new things,’ says Vogler. ‘Each time we meet, Bill mentions one or two new songs; but we’re not searching for anything. There is so much great material that we don’t have to – we just trip over it.’ He thinks of this collaboration with Murray, Wang and Perez as a casting for a movie: they are a set of complementary actors thrown together on stage. But despite its success, he emphasises that he is a classical musician at heart. ‘Bill is an actor; I’m a cellist,’ he says. ‘I feed my family by playing cello concertos and recitals, and I love doing that. And I’m sure Bill gets a new movie script on his desk every day. This project is extraordinary, but it is something that has come out of friendship, and that is the most important thing. We learn from each other and we play for each other, and it makes us totally emotionally involved.’

It showed. As Wang and Perez played a sassy but subtle ‘Blues’ movement from Ravel’s Violin Sonata no.2, Murray stood at his narrator stand, visibly awestruck. At the end of the show, the applause was deafening as he threw roses into the audience – so much so that it drowned out the trio’s final encore. Nevertheless, when bows left strings after the last note, the concert hall reverberated with an explosion of cheers.

The ‘New Worlds’ show is touring the US in April and Europe in June, including dates in London and Edinburgh. More details here

This article first appeared in The Strad’s August 2017 issue

Watch: a trailer for the New Worlds project featuring Jan Vogler and Bill Murray

No comments yet