In this article from January 2016, a quarter century after the Greek violinist made his pioneering recording of the Sibelius Concerto alongside its original version, he talks to Andrew Mellor about his relationship with the work

There’s something odd about watching Leonidas Kavakos rehearse the Sibelius Violin Concerto. For a man who won the Sibelius Competition in 1985 playing it, became the first to record the long-protected original version of the work in 1991, and has notched up hundreds of performances of the final version since then, what is there left to rehearse beyond the procedural rubric of tempi and orchestral balance?

More than you might think, it turns out. Accompanying Kavakos with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at Saffron Hall in the UK last October is Vladimir Jurowski, a maestro who has explored repertoire from Alfred Schnittke to Granville Bantock but who has conducted precious little Sibelius. ‘He is someone who has amazing knowledge of what is around the music,’ says Kavakos, ‘a person who is absolutely in the service of the composer.’ At one point, while obsessing for around 15 minutes over the balance between horns and a bassoon at the start of the concerto’s central Adagio di molto movement, Jurowski proposes that ‘the problem is, people hearing it [the concerto] for the first time won’t realise there’s a change in harmony there.’ Indeed.

But of particular interest is what the fresh air of detailed orchestral work on the concerto gives Kavakos – in both his guise as a prominent proponent of the piece and also as a conductor himself. ‘You always get something from musicians like that,’ he says, referring to Jurowski. ‘The problem is when someone arrives at a rehearsal who doesn’t respect the frame.’ The frame meaning the score? ‘Yes the score, but in what sense the score? In the sense of understanding that the score is like a rich landscape that includes hills, mountains, valleys, lakes, sea, sky. We have to understand that with this alphabet of twelve notes composers conceived certain material, certain ideas. Why is that motif there? What came before it? What came after it? If you look at manuscripts you see that apart from Mozart’s and Mendelssohn’s, they are generally full of corrections. Composers don’t just write the music, they search for it, try to understand where it’s going – to create that frame in a way that’s clear, and that works both emotionally and mentally.’

‘You should be able to reject all your knowledge’

Sibelius, for all the miracles of what he found at the end of that search, struggled in it more than most. The original version of the Violin Concerto contained hair-raising virtuosic challenges that the composer came to realise, ultimately, didn’t serve the bigger picture he was trying to paint. His revisions of the piece in 1905 were described by his British biographer Robert Layton as a process of ‘purification’. For a detailed insight into what they encompassed, look no further than the analysis offered by Andrew Barnett, another Sibelius biographer, on page 36.

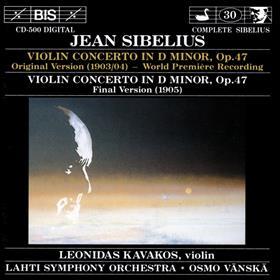

So for Kavakos, does that knowledge of the more episodic and showy original version colour the way he approaches the standard version, every time he picks up his violin to play it? ‘Not much, not any more,’ he says. After winning a Gramophone Award in 1991 for the recording of both versions with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and Osmo Vänskä (see page 34), Kavakos suggested that the two works share an equal footing – that the original version should be welcomed back into the repertoire.

But his opinion on that point has changed. ‘There is some fantastic material in the first version that I’m sorry is not there in the second,’ he says. ‘But when you look at the concerto as a composition, there’s no question which version is the best, and that’s the second one.’ In truth, though, Sibelius’s first thoughts are still somewhere in Kavakos’s mind; surely they can’t help but shape his thinking on the piece as a whole? ‘It was a revelation for me when I first looked at the score of the original version and the solo part,’ he admits. ‘It gave me enormous knowledge of what Sibelius was actually thinking, of the process of the concerto’s birth. What we have in the second version is what Sibelius distilled within himself. It’s more compact, it’s structurally perfect, and nothing is exaggerated.’

‘What we have in the second version is what sibelius distilled within himself’

The great virtuoso Joseph Joachim had a different description for Sibelius’s final version: boring. The composer responded that Joachim was out of touch with the emotions of the time, and with the luxury of hindsight we can safely conclude it was the Finn rather than the Hungarian who was correct. ‘The first version is impressive because it gives you an idea of how well he [Sibelius] knew the violin – he wanted to make it as difficult as possible technically,’ says Kavakos. ‘But that’s not the purpose of composing and Sibelius came to understand that. Thank God this first version was a catastrophe and that he realised it.’

Still, the concerto has never enjoyed the ‘unquestionable masterpiece’ status of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony (also revised) and so many more of his works. Some have questioned the concerto’s proportions and its unusual, stuttering ending. In the probing Sibelius exhibition mounted at Helsinki City Hall this summer, the conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste came straight out on a video interview and claimed that ‘these are not good times for the Sibelius Concerto… ideals of playing have changed.’His point, that our current penchant for the spectacular and our general lack of truck with the searching, shamanistic aesthetic of the Sibelius Concerto, is in some ways a valid one. Nobody these days, suggested Saraste, plays the slow central movement with the breadth and tenacity that Ida Haendel brought to it.

Not many, perhaps. But Kavakos is one of them, and it is easy to appreciate Jurowski’s work on the movement’s darkly lit opening as a result. ‘The colour changes completely in these bars,’ Jurowski said to his orchestra of that opening, and even this seems to have brought something extra out of Kavakos. ‘Many people who play this piece ignore the orchestration around it but I feel in this second movement we have a situation of a sound world that’s very specific, and the violin has to match that,’ the violinist says. ‘In no other violin concerto do you have such a long episode with horns playing at such a low register. The only other concerto with similar elements is the Bartók Second, where you have violin against woodwinds, violin against brass, violin against percussion, and Bartók’s genius is that he can make the violin sound like a flute, a horn, or even timpani. The Sibelius may be completely different, but it’s clearly not just about playing a melody. It’s about creating a world of sound, and that world of sound needs time.’

Time, and patience. Sibelius marked the movement Adagio di molto, and Kavakos stresses the point: ‘He could just have written Adagio.’ And with Saraste’s comments ringing in my ears, it’s interesting to hear just how tenacious Kavakos is in this slow movement, although he’s audibly applying the necessary reserve for a rehearsal. Even on a pianissimo, his tone is remarkably strong right to the tip of the bow (though perhaps that’s a Kavakos hallmark in itself). Some bars feel so filled with space they seem almost to hover in the air, bereft of time.

In its entirety – notwithstanding the brisk central episode – the second movement has a remarkable sense of inertia in Kavakos’s hands, of not feeling the need to get anywhere. It’s about more than the tempo, but an appropriate tempo is an important starting point. ‘If you’re going too fast, everything becomes insignificant,’ Kavakos says. ‘It’s like driving through somewhere at 300kmh. You’ll see more or less what is around you, but you won’t be able to understand much of it. And it’s exactly the same thing with this movement.’ As mentioned, though, it’s about more than tempo. ‘The long line works if you resolve the details. If you don’t figure those out, no matter how fast or how slow you play, the long line won’t work. The more time you have to articulate the smaller particles, the more the construction lives.’

Kavakos the conductor is known for his pithy explanations and contextual ideas – ideas that help orchestras crack his interpretative plans with speed. So how would he explain the human ideas behind this movement? ‘This is someone who knew about being a violinist, who knew what that G string means to violinists – to have that great deep sound on an instrument that’s mostly high, effectively a soprano instrument. Sibelius had this in mind, and you have to acknowledge that.’

But isn’t the movement about more than the depths of that opening? ‘Yes, and of course there is the unbelievable contrast between the beginning, with its dark violin solo, and the middle section which is very high, with a sort of chorale. The music ascends with respect, with love, with humility, but also with desperation.’ For Kavakos, it’s a desperation linked to Sibelius’s hopeless ambitions of being a virtuoso on his instrument.

‘This is clearly someone who had a dream for his violin playing, and [the music is] about his desperation over not being so great. For me it’s like carrying the cross: each step is difficult. That’s why you can’t take it too fast. Because when it’s too fast it becomes easy to play, and then you suffer less emotionally.’

‘The music ascends with respect, with love, with humility, but also with desperation’

What follows, of course, couldn’t be more different. Sibelius might have trimmed down his finale in the 1905 revision, but the movement retains its singular combination of lightness and weight. That’s tricky enough to capture, before a player considers the movement’s frequent staccato double-stops, its rapid, string-crossing runs, its treacherous octaves and delicate harmonics. ‘The hardest thing about the concerto is playing the third movement, because I’m always exhausted by the time I get there,’ Kavakos admits. ‘The first is already quite strong, the second wears me out and the third is also dramatic but extremely hard technically. So I always finish the second movement and I don’t know if I can sustain the third. I feel this on stage every time – always, exactly the same: oh no, I cannot do this, how can I sustain this?’

![]()

Spare a thought for those violinists who, after Kavakos, have tackled the trickier original version of the piece, and that final movement, following its emancipation at the hands of the Greek violinist and the record label BIS. But we shouldn’t expect Kavakos’s interpretation of the concerto, in any form, to stand still. Having performed the final version in San Francisco and Philadelphia in November 2015, and with Saraste in Copenhagen in December, he plays it again in January in Dresden. And if the process of osmosis I witnessed with Jurowski happens every time, Kavakos’s performances are set to keep changing, little by little.

That’s a concept at the heart of his creative outlook. ‘If you ask me how many times I’ve played the Sibelius Concerto, I don’t know, but it’s definitely in the hundreds,’ he says. ‘So what does that mean – that I should have had enough of it?

‘No. I’m still changing, I’m still thinking, I’m still trying to understand if I’m doing right or wrong, if I can convince myself in my decisions or not. I think this is how human beings should be. You should be able to reject all your knowledge in one day, if you’re convinced you need to, and restart from zero. If you don’t have that attitude, how can you keep playing the same pieces again and again for so many years?’ There can be few more pithy or wise reflections on the life of a musician than that.

The January 2016 issue, in which this article first appeared, is available as a back issue in The Strad Shop

No comments yet