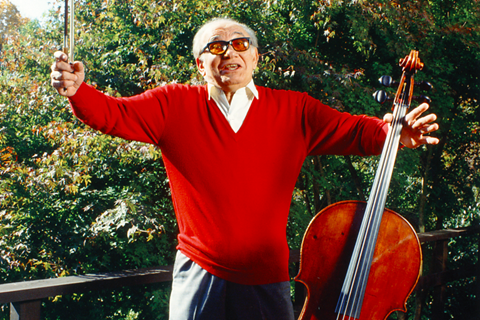

The venerable cello teacher, who celebrates his 100th birthday in September, recently announced his retirement from the Yale School of Music. He shares his insights and looks back at the beginnings of his distinguished career

Try as hard as you can to find out who you really are and then convey it to the audience. When you’re performing in public, you’re there to tell a story. That does not involve staring at your fingerboard – there’s nothing there to help you! Look at the audience instead of the darn fingerboard. Sure, you can glance down occasionally, but you mustn’t let it get in the way of what you want to do musically. Aside from all the technical aspects of cello playing, the most important thing my teacher Tomazzo Babini taught me was to project my personality – and how to do it.

I respect people for doing things differently but, as far as I’m concerned, there’s nothing new on the market

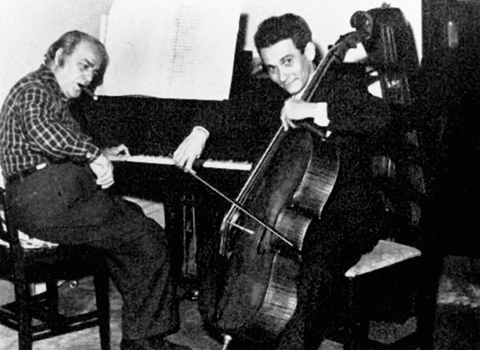

Two years after my father dropped dead of a heart attack, my mother married Tomazzo, an Italian who had been principal cellist of the orchestra of La Scala in Milan. He was born in 1885 and later moved to Rio de Janeiro – where he became friends with Villa-Lobos – before settling in Natal in eastern Brazil, where he met my mother. After I had heard the beautiful sound of his playing, I told my mother I wanted to learn the cello and begged her to let me study with him. I was four. At first, he didn’t want to teach me because he thought a child of my age would quickly become bored. Of course, that wasn’t the case, and he soon realised I had potential. Tomazzo was both my stepfather and the only cello teacher I ever had: everything I know I owe to him. He introduced me to my first audience while I was still wearing short trousers and remained my mentor until his death in 1949.

I have an incredible affinity with Bach. In the beginning, I had no idea whether I was playing his music right but I knew that I loved it. In a way, that’s the greatest thing about Bach’s works – they’re so full of mystery that there are infinite ways of playing them. People look for answers to every question, but they aren’t always there to be found. No one set of bowings or phrasings is the ‘right’ one. Your version will always be at least as good as any other because its origin is inside you.

I pay attention to changes in string playing, and I respect people for doing things differently but, as far as I’m concerned, there’s nothing new on the market. I’ve never lost my optimism, about music or anything else, but I think that there is a limit to everything. The greatest experience for me is hearing one of my students and being so moved by their performance that I forget they are playing a cello at all.

INTERVIEW BY PARISOT’S FORMER STUDENT RALPH KIRSHBAUM

This interview is from The Strad’s September 2018 issue, which can be downloaded on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or in print

No comments yet