In this article from 2016, the Lithuanian cellist reflects on how Bach’s Cello Suite no.1 has influenced some of the key moments of his life

I began playing the cello aged six, and by the age of nine or ten I was practising Bach’s Cello Suite no.1 in G major. I played in a youth orchestra for six years, run by the conductor Saulius Sondeckis (1928–2016). I remember one rehearsal when I was sitting practising the suite by myself, Sondeckis heard me and remarked, ‘My goodness, that’s fairly advanced for someone like you!’ Somehow that had an exhilarating effect on me – that this maestro who I looked up to had taken an interest in me because of this piece. From then on I practised it even more assiduously than I had before.

When I was 17 I was accepted into the Moscow Conservatoire, where I was very fortunate in that Mstislav Rostropovich happened to have one free place in his class. After scales and etudes, the Cello Suite no.1 was practically the first piece we practised with him. One year later, aged 18, I gave my very first public recital in my home town of Vilnius, Lithuania. I chose to perform this suite, having studied it during the previous year.

At that time, we were all encouraged to play the First Suite legato throughout. But fashions change – nowadays there’s much more variety in the ways one can play the Cello Suites, and all are regarded as legitimate interpretations. Someone at that recital told me that my playing of the opening Prelude reminded them of a forest, which was the first time I’d heard my playing compared with nature. But words of inspiration can capture your imagination without you looking for them.

I once attended a masterclass given by Paul Tortelier, where he suggested that the First Suite put him in mind of the sea, with its waves of colour and line lapping back and forth like the tide. In the 1980s or 90s I attended a concert by Tortelier at La Scala, Milan, where he began the performance by playing the Prelude of the First Suite. He prefaced it by remarking that Bach’s name made him think of a ‘Bächlein’ (little brook), so that he imagined the cello line flowing like a stream. When he played I understood what he meant – it had a fluency and drive to it that I hadn’t heard in previous performances.

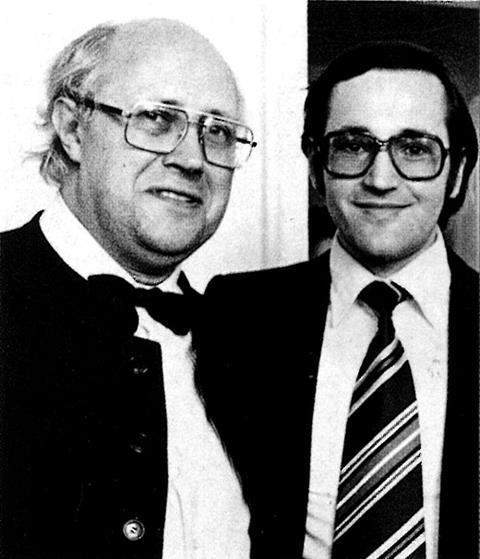

Since then I’ve tried to adopt that way of playing, to recapture that sense of flowing like a babbling stream. When I was 20 years old my fiancée, the pianist Tatjana Schatz, asked me to play something special, just for her. I chose the First Suite as a kind of show-off piece – it seems to have impressed her, as we’ve now been married for almost 50 years.

I think of the First Suite as very pure, natural, wonderful music. During my lifetime I’ve seen so many cellists return to it after playing works that are more difficult technically, simply because it’s irresistible to play. Each one of the Suites has its own special beauty; sometimes people seem to believe that beauty goes hand in hand with technical difficulty but after years of working on different pieces you come to the realisation that simplicity can be beautiful.

I’ve heard it said that Bach was the first jazz musician, given his love of improvisation and the importance of the bass-line in performance. His works always have both depth and narrative drive. In the past I have played the Suites accompanied by a jazz percussionist, who gives them a different tempo, and it’s a measure of Bach’s genius that his works can bear such interpretations.

In 2011 I recorded all six of the Suites alongside fragments of works by various contemporary composers, such as John Corigliano, Ernst Krenek and Sofia Gubaidulina; this ‘Bach Plus’ project showed me that the Suites are among the most universal of pieces, and can fit alongside almost any compositional idiom or stylistic era.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

This article was first published in the March 2016 issue of The Strad

No comments yet