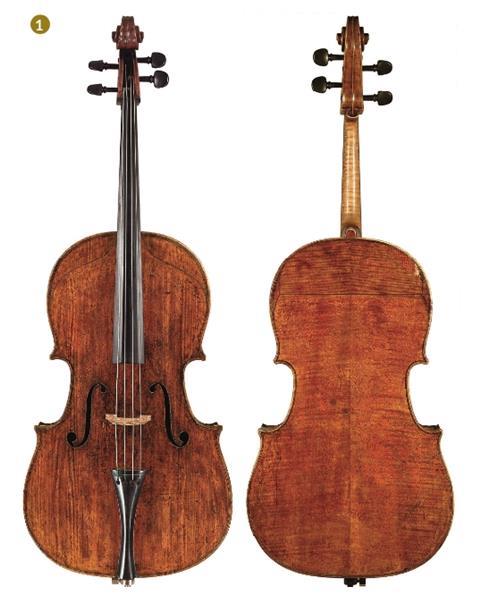

In an article from June 2015, Matthew Zeller examines five centuries of alterations made to the world’s oldest cello, housed at the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota, and asks what they reveal about the evolution and development of the standard cello form

Made in the mid-16th century, the ‘King’ cello by Andrea Amati is a prime example of an instrument that is not what it once was: it has been drastically reduced in size. Alteration stood at the forefront of musical instrument development during the last quarter of the 18th century and throughout the 19th. Changing the size of an instrument is just one of many types of alteration that are as important to the study of music and musical instruments as an appreciation of makers, composers, performers and performance practice. Understanding how an instrument was altered is the first step to understanding its place in the larger study of instrument evolution.

The terminology referring to the early forms of cello is convoluted and inconsistent. Andrea Amati would likely have referred to the ‘King’ as the basso (bass violin) of the family, as numerous 16th-century musical treatises attest. The first publication of the term ‘violoncello’ was in Giulio Cesare Arresti’s 12 Sonate a 2 et a tre (1665). In this article I refer to the ‘King’ prior to its reduction as a basso, and in its current form as a cello. The alteration of large-format instruments like the basso into what we recognise today as a cello was not performed out of any disregard to the instrument; it was merely a transformation from an obsolete form to one that was more functional at the time. After all, audiences of the day did not want to listen to old music – they went to concerts to hear new music.

It should come as no surprise that instrument sizes have been the subject of much experimentation. Even today there is no established size of viola, only an acceptable range, limited mainly by the physical capabilities of the player. Throughout almost the entire Cremonese period, from the Amati family to the deaths of Stradivari and Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, the body sizes of the viola and cello were subject to experimentation. Only one generation after Andrea Amati established his family of violin instruments, his son Girolamo began experimenting with viola sizes. The Ashmolean Museum houses a viola by Andrea with a back length of about 470mm and a 1592 Girolamo Amati viola with a back length of 452.5mm, dissimilar from any other known instrument by the makers of the Amati family. Girolamo also made the first documented Cremonese contralto viola (with a back length of 411mm) in 1615, the ‘Stauffer’.

Later in the Cremonese period, Stradivari also experimented with instrument size. His violin patterns evince this, but this experimentation can most easily be seen in his cellos. Although they are not as large as the Amati basso, the ‘Medici’ (1690), ‘Castelbarco’ (1697), and ‘Servais’ (1701) cellos are examples of large-format instruments with back lengths that are 35-40mm longer than the smaller-size cellos, such as the 1711 ‘Duport’, which came to be popular with cellists.

The transition from large to smaller-sized instruments was echoed by changes in music: as the basso was gradually superseded by the cello, its musical uses went from continuo playing to more demanding repertoire, and later still the cello became a soloist’s instrument. By 1801, the date that the ‘King’ might have been reduced, large-format bassos were obsolete, discarded in favour of the smaller-bodied cellos. Nearly all large-format bass instruments, not just bassos of the violin family, were subject to alterations in size, and many bass viols were altered to become flat-back cellos. Creating a cello from a bass viol involves enlarging the instrument rather than reducing it, an example of which is the 1727 Stradivari ‘Fruh’ cello (figure 1, National Music Museum; Vermillion, South Dakota; NMM 10845).

The first published description of altering an instrument’s size can be found in the book La chélonomie, ou le parfait luthier, published in 1806 in Paris. It was the result of many discussions and collaborations between Abbé Sébastien-André Sibire, a well-travelled and educated cleric and violin enthusiast, and Nicolas Lupot, the premier French violin maker and restorer of his time.

As Sibire explains in this section on altering a Stradivari bass viol, changing an instrument’s outline is not without its dangers: ’I had the misfortune, a few years ago, to consent to the degradation of a magnificent basse de viole by [Stradivari], hoping to create from an out-of-style instrument a magnificent and wonderful violon that would still be [the work of ] the same maker. I was mistaken in my expectation: the ill-fated extract broke apart in the mould; pieces remained, Stradivari had disappeared. This operation, which took from me a great deal of money and remorse, has only left me the precious surplus [of the instrument].’

Fortunately, the ‘King’ cello did not suffer the same fate. But from this snippet we not only learn of the dangers of altering an instrument’s outline, we glean an important fact of the time: this Stradivari bass viol was obsolete. Large bassos and bass viols were altered to become useful cellos for contemporary music. So it was with the ‘King’.

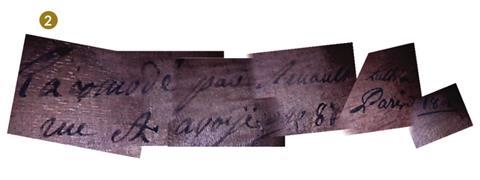

Little is known about the reduction of the ‘King’ other than the basic information from the inscription on the inside of the back (figure 2). It reads: ‘Mended by Renault Luthier, St. avoÿe street, __ 8_ Paris 1801.’ It cannot be stated with certainty that the luthier Sébastien Renault, who was active in Paris from c.1765–1811, was responsible for the current state of the instrument in its entirety, but it is certain that he had a hand in it.

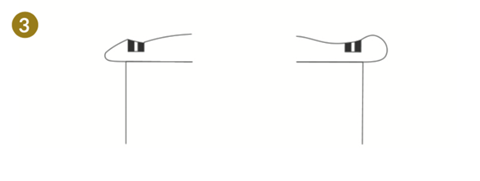

The belly and back plates of the ‘King’ have both been altered, but not in the same fashion. An examination of the purfling, edges and corners of the instrument provides clues about the manner of alteration and the original outline. The only edgework remaining on the ‘King’ that is by Andrea’s hand is on the back through the bass-side middle bout, including both corners. This is also the only portion of the instrument that retains its original edge fluting. Around the remainder of the perimeter there is a distinct lack of edge fluting, the arching runs straight into the edges. The edge profile varies considerably around the perimeter of the instrument, an example of which can be seen in figure 3.

The purfling on the ‘King’ cello seems to be anomalous in the extant body of work by Andrea Amati. There are two types of purfling present: the first has ebony blacks and either a maple or poplar central white strip, while the second type is the same fruitwood throughout, likely pear, apple, or rowan, with lightly stained blacks. Typically, the blacks of Andrea’s purfling are made from a heavily stained fruitwood and the white strip is either maple or poplar. In the case of the ‘King’, it appears that Andrea may have used ebony for the black strips. It is possible that the sections of purfling containing ebony are not original, but the edgework, purfling inlay, and mitres of the bass-side corners on the back suggest that the sections of purfling with ebony blacks are in fact original sections of purfling by Andrea. There is also a small section of this purfling on the belly, in a portion of the bass-side middle bout. The lightly stained fruitwood purfling does not show the workmanship typical of Andrea Amati.

The corner on the lower bass-side of the back is the best preserved of all those on the ‘King’ cello, and exhibits the typical shape of an Andrea Amati corner (figure 4). The curves of this corner have a flowing elegance not present in the other corners; the curve coming into the corner from the middle bout continues past the mitre joint in the purfling, yielding the long, hooked shape typical of Andrea’s corners. The upper bass-side back corner shows some indications of a flattening of the arcs entering the corner, however it still retains the overall impression of a corner by Andrea. The middle bouts on the back are not symmetrical and the treble-side bout curve and corners are drastically altered. The treble-side back corners do not show the long, hooked corner shape that Andrea consistently carved. The curves entering the corners have been flattened well beyond anything that is consistent with the usual wear patterns. Their shape is indicative of being carved down in size to reduce the width of the instrument.

All four corners on the belly are significantly altered.

On the treble side of the belly, the wood joints where new corners and edgework were added are squared off and easily visible. The same can be said for the lower corner on the bass side of the belly. The bass-side corners of the belly are crudely pinned, perhaps to serve as locating pins during the reduction (figure 5). The only corner on the belly that retains any resemblance to a corner by Andrea Amati is on the upper bass side. The curve entering this corner from the middle bout appears less altered than the rest of the belly and is the only remaining section of edgework on the belly that resembles the work of Andrea. There is a section of the purfling with ebony blacks emanating from the lower portion of the upper corner mitre and terminating in a joint prior to reaching the lower corner. However, this section of purfling and edgework lacks the elegance of Andrea’s work and does not give the overall impression of being unaltered.

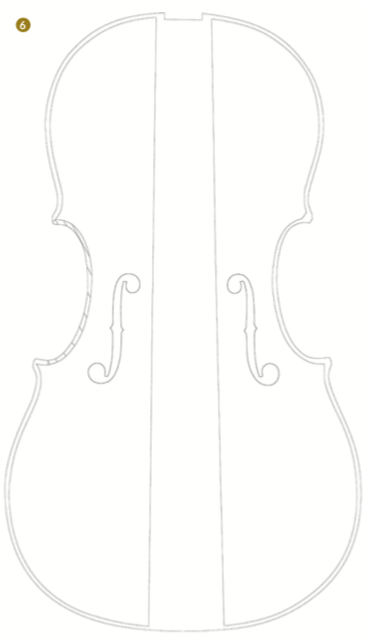

The belly has a strip of non-original wood running down its centre ranging in width from 63.5mm at the neck to 92mm at the saddle. The only original pieces of wood remaining on the belly are the two planks containing the f-holes, which run between the centre strip and the severely altered edgework (figure 6). The f-holes are essentially independent from their original placement by Amati because of these alterations. The treble-side f-hole has also been significantly enlarged. It appears to have been the unfortunate recipient of careless soundpost adjustment over the years and poor judgement in attempting to repair the damage by recarving the f-hole.

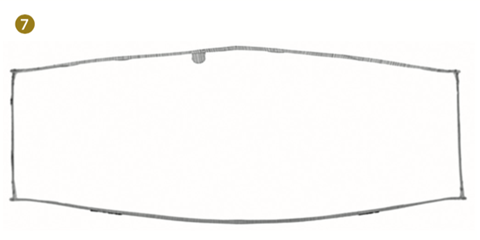

The strip of material through the centre of the belly has a pointed peak running down the centre line of the instrument. The wood joints at the centre line, and those joining the central strip to the planks containing the f-holes, are not well made. As can be seen in a CT-scan cross-section (figure 7), there is a marked variation in plate thickness at the various wood joints. The varnish on the belly is different from that of the rest of the instrument, and that on the central strip of wood is clearly different from the rest of the belly varnish, indicating work performed at different times.

Overall, the back is better preserved than the belly. A large, slightly tapered strip of material has been removed from the centre line of the back, but unlike the belly, new material has not been inserted. The upper and lower bout extremities have been cut down and the treble-side middle bout has been cut inwards toward the centre. Most of the edgework is not original, but the interior of the instrument represents Andrea’s hand, excepting the portion that has been removed from the centre. The painted decorations on the back aid in determining the alterations made to the instrument. Figure 8 shows an estimation of the original outline and a reconstruction of the decoration.

There is a series of repairs, damage marks, and what appear to be burns that also provide clues about the instrument’s history and original size. The apparent burn marks at the base of the lower bout are accompanied by a section of non-original edgework and the arching runs straight into the edge with no fluting. It is possible that the wood was scorched during an attempt to reverse the curve of the arching by bending the wood.

There are three plugged holes in the lower bout surrounded by circular indentations on the ‘King’. Such holes are also present in similar locations on another Andrea Amati cello, once owned by the Lyon-based luthier Jean Frédéric Schmitt (1937–2012). They appear to be remnants of a holding system for the instrument. During the Renaissance, instruments were commonly played in processions and dance arrangements and must have been secured in some manner for playing during movement.

In his 1556 Epitome Musical, the composer Philibert Jambe de Fer wrote about the need for instruments to be easy to carry for accompanying purposes, and mentioned a way of supporting the instrument with ‘a little hook in an iron ring, or other thing, which is attached to the back of the said instrument quite suitably, to the end that it does not hamper he who plays upon it’.

There is another plug in the bass-side upper bout and there seem to be the remnants of another circle at the shoulder of the bass side near the neck, supporting the idea that the plugged holes and marks in the lower bout are remnants of a support system akin to that mentioned by Jambe de Fer. The plugged holes could be where a post was inserted and the circular damage marks could be from rings attached to the posts that held straps of some type.

The fact that the ‘Schmitt’ cello appears to have these same plugs and circular damage marks in similar locations as the ‘King’, combined with the similarity of the two instruments’ decorations, seems to indicate that these two cellos were used in the same manner and enhances their attribution to being part of a unified set of instruments.

The head of the ‘King’ cello is the only part of the instrument that remains unaltered, and it is remarkably well preserved. It exhibits many of the traits one would expect from a head by Andrea Amati. The volute is well formed; traces of the compass marks in the centre of the eyes are visible. There are also compass points along the centre line of the head and the central spine terminates in the typical manner for Andrea Amati (figure 9). The ribs have been reduced in both height and length. However, due to its complexity, a discussion of the ribs falls outside the scope of this article.

Though altered in different manners, both the belly and back of the ‘King’ cello have had material removed from the centre line of the instrument and from the edges. The back is a better representation of Andrea Amati’s work than the belly, and the bass-side corners and middle bout of the back are typical of Andrea’s work.

The ‘King’ cello would have had a back length of approximately 840mm at the time it was made, 89mm longer than its current size (measured in a straight line with callipers, not over the arching with a tape). Respectively, its upper, middle, and lower bouts are now approximately 83, 54 and 69mm narrower than when the instrument was first made.

Sébastien Renault certainly worked on the cello in Paris in 1801, but it cannot be said what he is responsible for. Whether he reduced the ‘King’ or if he mended it after the reduction was performed by another luthier, the cello can be placed in his workshop around the time that reducing obsolete instruments was in fashion in Paris. Without its alteration in size, the ‘King’ cello may have been neglected or lost to time as many other fine instruments have been, and we would be at a loss without its beauty.

Finally, the ‘King’ cello is the best preserved of the basso instruments by Andrea Amati and is a fount of information about both instrument making and performance practice during the 16th century. Studying its reduction is essential for a complete understanding of the changing roles of the cello during this time period, and to help us understand the evolution of music and musical instruments during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

All Drawings by Matthew Zeller

All ‘King’ photos Bill Willroth Sr/National Music Museum

Figure 1 Tucker Densley/Jim Warren/Chris Reuning/National Music Museum

Figure 7 Courtesy Sanford Hospital, Vermillion, South Dakota, US.

Read: Girolamo Amati II violin 1671: Last but not least

Read: A Massive Achievement: the ‘Romanov’ Nicolò Amati viola

Knopf dynasty: A tangled web

Three bow makers of the Knopf family are well known: Christian Wilhelm, Heinrich and Henry. But the dynasty comprises more than a dozen members, many of whom deserve recognition. Gennady Filimonov draws on archive material supplied by the Knopf descendants

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Deconstructing the Andrea Amati ‘King’ cello

No comments yet