The country’s Unesco-protected orchestral system may look ideal to the rest of the world, but it’s by no means a bed of roses, writes Hugo Shirley

An article about classical music and Germany from the Financial Times late in 2017 began by referring to a contest in China. The combined might of the Berlin Philharmonic and the Dresden Staatskapelle had prevailed against players from the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra.

The contest? A football friendly. But it was nonetheless interpreted as ‘one more small symbol of German dominance in the world of classical music’.

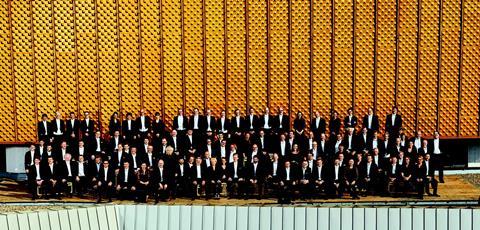

The Far East got its revenge when South Korea dumped the German national team out of the World Cup some six months later. But if the German national game is now in crisis, few would argue with the suggestion that Germany remains dominant in classical music. Its orchestral scene, for example, is second to none, its hundred-plus orchestras and theatres recognised with ‘intangible cultural heritage’ status by Unesco. From afar, it looks to many like a musical paradise.

That Unesco status, however, serves more as a preservation order than a stamp of recognition: it was hard won through a long campaign, and assured only through strikes following the gradual orchestral mergers and closures that were steadily laying waste to the landscape. Nor is Germany a stranger to those familiar laments about dwindling audiences or the death of the art form. Increasingly, too, there are rumblings of discontent to be heard from its younger musicians, emerging from their training to find the reality of musical life isn’t what they expected.

Musicians go from one temporary contract to the next in the vain search for a permanent position

Germany might have more orchestras, but it also has more musicians (including those flooding in from abroad) looking to fill positions in them. The audition procedure is often archaic, unnecessarily nerve-racking and, with strict voting systems, sometimes deeply frustrating. Musicians go from one temporary contract to the next in the vain search for the security of a permanent position.

The extent of the problem is such that the Berlin-based online magazine Van has addressed it in a series of articles. They highlight the slowness with which the German Musikhochschulen have adapted to the modern status quo, whereby a freelance career closer to that practised widely in the UK is a more realistic expectation. One violinist I spoke to – currently hopping from one job and audition to the next – told me that her conservatoire didn’t even cover the basic practical aspects of freelance life, such as how to cut down the high cost of health insurance that is a legal requirement in Germany.

At the same time, a player from one of Germany’s top orchestras tells me how some hopefuls come to their auditions insufficiently prepared musically, suggesting that the conservatoires are failing on a more fundamental level, too.

Other musicians, she explains, prolong the inevitable: after their basic training and diploma – which can easily run to six or seven years – they stay on at the conservatoire, collecting qualifications from specialist courses (chamber music, Baroque performance or similar), which if anything render them even less employable. And as in so many industries, there’s a generation gap, the view of which is sharpened by frustration and impatience among younger players, who see the older generation enjoying all the securities while even the very best young musicians have to fight it out for scraps.

There’s evidence, though, that the conservatoires in Germany are adjusting – or are feeling the pressure to do so. In many ways this brings them into line with those in other countries already offering training in the practical realities of being a musician in a climate of shrinking funding for the arts. Maybe in Germany we’re seeing the musical equivalent to a First World problem: are German musicians simply having to adjust to a situation that brings them closer to the reality for players in the rest of the world?

No comments yet