Covid-19 has highlighted the economic inequalities that divide musicians who perform on period instruments from the majority of today’s string players, says Andrew Mellor

Might we be on the brink of seeing the dust from Covid-19 settle once and for all? Whisper it, but it seems so. After two years of false dawns, dashed hopes and seemingly endless economic pain, the arts sector might at last be able to take stock of the havoc wreaked upon itself, and start to rebuild.

And we must, to use a cliché, build back better. Lots has been said and written about what that phrase might actually mean. There have been inspiring steps forward, chief among them the truth that yes, it is possible to plan a classical music concert at a few months’ or even weeks’ notice. But there have been just as many disheartening signs of business as usual.

Perhaps the most salient lesson learnt by instrumentalists during the pandemic was that there’s clearly a two-tier system in operation – one that kicks in during situations like that we have all endured these last two years. If you are paid a monthly salary from an orchestra or opera company, that salary will likely continue to land in your bank account, pandemic or no pandemic. If you’re a freelancer, your income will either disappear or be held to ransom by the policies of particular government help packages.

Maybe that’s fair enough. Freelancers decide to be freelance for myriad reasons, one of which is the flexibility that comes from being able to choose how, when and where to work. Perhaps fewer instrumentalists and singers will choose to be freelance after the pandemic, knowing that when the next one comes they’ll likely be left with nothing.

But not all freelance musicians have the luxury of choice. Almost every standing civic or opera orchestra in the world employs musicians playing on modern instruments. Where does a specialist early instrumentalist turn if they want to play in a standing, salaried orchestra? Is there a single orchestra in existence that will pay such a musician a salary all-year round? I do not know of one.

‘Perhaps fewer musicians will choose to be freelance after the pandemic’

It seems clear that instrumentalists who specialise in playing on period-specific instruments – and have spent years honing the associated technique – are destined for a freelance life whether they like it or not. They are rarely, if ever, presented with the option of playing in one venue in one city for years at a time. This has all sorts of implications for family life, even beyond the financial stability that comes with earning a salary.

We’re all aware of the reasons for this. Nobody expects symphony orchestras to confine their repertoire to the 17th and 18th centuries and replace all their players. But there needs to be a conversation about the lack of stability forced upon musicians who specialise in a particular area for creative reasons.

We might also ask if some of the major musical cities of the world could benefit from employing a standing orchestra of period instruments. That seems entirely viable in Tokyo, Amsterdam or Berlin, where the market is sufficiently large and there are numerous symphony orchestras that replicate each other’s repertoire. It would also help lower the carbon footprint of an early music sector over-reliant on long-distance touring.

As the harpsichordist and artistic director of Concerto Copenhagen, Lars Ulrik Mortensen suggested to me in 2020, the day before Covid-19 became a national concern in his country: ‘It doesn’t seem a completely far-fetched idea that one of the fully funded orchestras in Denmark could be allowed to be a little bit different from all the others.’ Never has Baroque and Classical music enjoyed such mainstream popularity – nor such expectations of expertise. Now is the time to address the place of period instrumentalists, forced for too long to exist, economically, at the margins of the profession.

Read: Applying for funding: an insight from Tina Vadaneaux, Continuo Foundation

Read: ‘There’s nothing like a good bass-line!’- the role of a continuo player in Baroque music

-

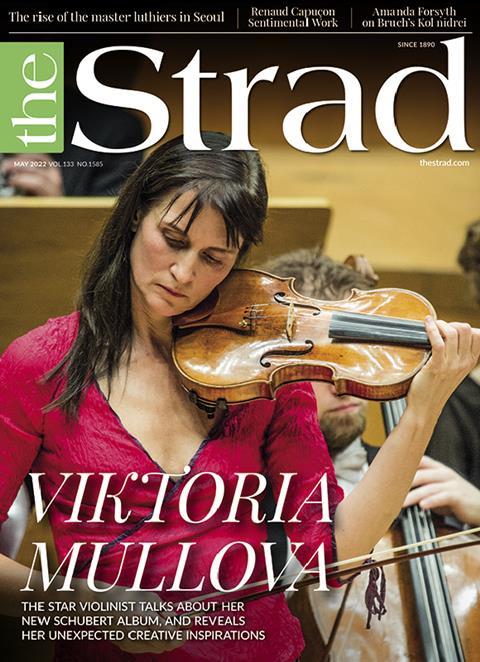

This article was published in the May 2022 Viktoria Mullova issue

The violinist discusses her latest Schubert recording with Toby Deller, as well as her collaborative projects with friends and family, and her love of improvisation. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet