Classical musicians can feel concerned about their lack of consequence in the ‘real’ world. But, as the pandemic has shown, the art form is needed now more than ever – and it’s up to performers to make the case, writes Andrew Mellor

Protecting its trainee musicians from the scourge of daytime television, the management of London’s Southbank Sinfonia organised a series of Zoom conferences during the initial Covid-19 lockdown. I was asked to lead one of them with the conductor André de Ridder. Under the title ‘How Others See Us’, the idea was to talk to the orchestra’s graduate musicians about how the rest of the world views classical music.

In a sense, we intended our talk as a reality check. If you’ve spent 15 years or more training to play an instrument at an elite level, chances are that you’ll have demonstrated immense personal focus while spending inordinate amounts of time with a lot of people from a similar background doing exactly the same thing. For most people outside that background, this world is as alien as the music it produces.

But we also wanted our session to instil in the orchestra’s members the idea that the ‘real’ world’s ambivalence towards classical music can be an advantage; that a lack of preconceived ideas about the art form presents huge opportunities. For many, the issues we consider to be our industry’s persistent problems – what people are wearing, how we programme concerts – simply don’t register.

Plenty of talking points emerged from the discussion, but it was inevitably coloured by fear – mostly, the fear of young musicians in lockdown who felt their careers were over before they’d started. When we opened questions to the floor (or rather, ‘the screen’), one cellist spoke for many when he asked how he and his colleagues could prove themselves and their work more ‘relevant’.

The R-word has ignited intense debate in UK classical music circles, not least after ‘relevancegate’: a misunderstanding of an Arts Council pronouncement on the principle of relevance, in relation to funding decisions, back in 2019. Immediately, sectors of the classical music industry were up in arms over the assumption that a focus on relevance meant drawing money away from them – a tacit acknowledgement that they believe their work irrelevant.

Read: Opinion: Being conscious

Read: Original and the best?

Read: Jedi wisdom for string playing

My message to the Southbank Sinfonia cellist was simple: nobody can tell you one of your performances is irrelevant if it’s heartfelt and honest (with a narrow slither of exceptions). The assumption that a piece of music written in a different age is automatically irrelevant is plain wrong. Yes, much music of the past is irrelevant, but history tends to see to it that we don’t hear that music any more.

The year 2020 proved that in some style. This is when we celebrated Beethoven, a composer whose message of social justice has rarely sounded more essential. Worldwide lockdowns have proved how much people need live and collaborative performance, resulting in a flood of creativity that has linked arms across boundaries linguistic, cultural and ethnic. If people come away from a performance of The Marriage of Figaro, Shostakovich’s Symphony no.5 or Jennifer Walshe’s Everything Is Important without feeling their relevance to everyday situations, then we have failed to contextualise them adequately.

But the point is deeper and broader than that, because music is an act of communication in which the power lies exclusively with the performer. In the case of notated music, that performer has the capacity constantly to reinvent and recontextualise the work without defacing it. This is the power of the musician. Not only will future generations need to call on it more intelligently and sincerely; with the car crash of Covid-19 behind us, they will be compelled to do so.

Of course, it might happen entirely naturally when our world is shaken out of its slumber post-pandemic. But we don’t have to wait for that to remember that there’s nothing irrelevant about the best music ever written, whatever the genre. The fact that it’s never been more relevant is something the musicians can confidently base their careers on – and must.

-

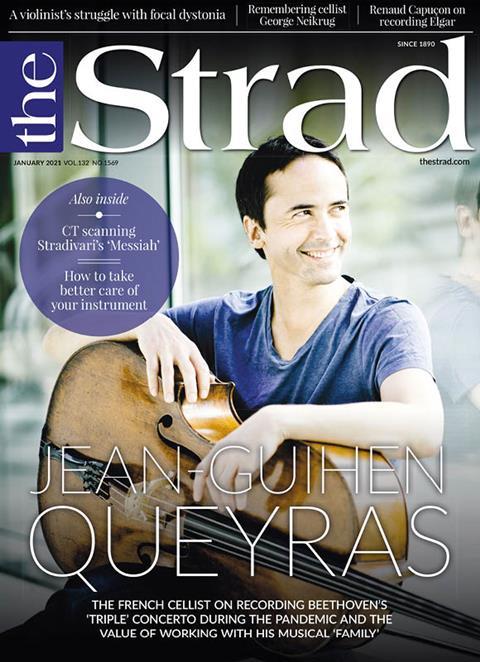

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more playing content here

No comments yet