A teacher can never rest on their laurels with a pupil – it’s important to keep observing how things are going and ask questions, says Naomi Yandell

There is no doubt that 2020 will live long in the memory as the year dominated by the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. This has got me thinking about my research chemist father, now sadly no longer with us. He would shudder as he mentioned the Spanish influenza outbreak of 1918 and prophesied that a new pandemic was one of the biggest but least prepared-for problems that the world would face in the future. In retrospect, I realise that I paid scant attention; his professional world and mine didn’t seem to connect in any way, and chemistry was my least favourite subject at school.

As I listen to the news and hear of scientists racing to perfect vaccines and potential new treatments, I imagine them poring over their spreadsheets, deciding which drugs to trial. Once the trial is up and running, I picture them checking for anomalies and patterns of reaction and I realise that our worlds have more in common than I had previously thought. Indeed, careful ongoing observation is a pretty valuable asset in many walks of life, and definitely in string teaching.

Take the establishment of a good bow hold. People often comment that a student ‘has a lovely bow hold’ as though it is a job done. The reality, though, is that however impressive a bow hold is at a particular juncture, a good first teacher will always look to develop it further, rather like a sculptor shapes and polishes a rough but promising piece of stone. This work will be subsequently refined by a later teacher, who is most likely to focus in on the detail.

Ongoing observation is key. It is well known that all manner of unwelcome habits can creep in over a period of time away from the teacher. These often start small but if uncorrected, they can become pernicious. At beginner level, a cellist’s right-hand little finger that falls softly over the stick at the end of term may, over unsupervised time, move up the stick in order to feel more ‘secure’, straightening in the process. First fingers have a tendency to creep imperceptibly along the stick, especially when playing the A string if the elbow is too low. Indeed, one of the reasons why teaching on Zoom is particularly exhausting is that great focus is needed to scrutinise tiny shifts in the placement of a finger or in the angle of an arm and to hear the consequent alteration in the sound. A teacher’s eyes and ears may (no, will) strain to assess what is happening.

Read 5 benefits to teaching online by violinist Rodney Friend

Read Teaching chamber music: light-bulb moments

Read How I started teaching students in Mozambique over Zoom

Of course, close observation of the student is important in other aspects of their learning. Reaction to the choice of repertoire is particularly important in maintaining motivation levels. Body language can speak volumes, especially when a teacher asks to hear a certain piece; though getting to the bottom of the issue may require some ingenuity. Among the questions a teacher might ask themselves are: does the student dislike the piece and hasn’t the self-confidence to say? Is there a passage where they are struggling? Is note reading an issue? Can it be that the standard of their pieces is, overall, too demanding? Might it be best to give an extra piece that they can enjoy without a sense of struggle?

Body language, often subtle, can also give a sense of whether a student’s self-esteem (essential for good progress) has been dented. A bolstering pep talk could be just the thing for some personalities; others might feel boosted by the idea that the teacher and student are working together as a team.

Experience helps us to see the larger patterns of learning, but within that there should be a myriad of approaches to suit each student. A teacher’s prime concern should be motivating a student to practise, thereby enabling detailed work and accelerated progress.

Throughout this pandemic there has been a cry to ‘follow the science’. This is somewhat spurious; we can arrive at truth from many perspectives. But above all, we do need to listen, notice and react; it turns out I have more connection with my father’s professional way of thinking than I imagined.

-

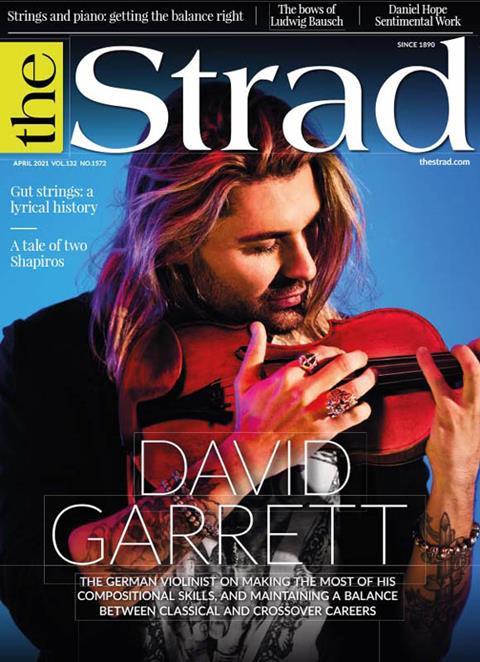

This article was published in the April 2021 David Garrett issue

The German violinist talks about making the most of his composition skills, and maintaining a balance between classical and crossover careers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Crossover star David Garrett

- German bow maker Ludwig Bausch

- Janusz Wawrowski: Session Report

- Germany’s 19th-century gut string makers

- Two Shapiros: 20th-century US female violinists

- Creating a balance between strings and piano

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet