Scouring the archives for early drafts is fine in the name of research, but when it comes to performance, the composer’s revised version is usually the more satisfying option, writes Charlotte Gardner

You know something’s building up to an opinion-shaped tipping point when a press release’s headline prompts a ‘not another one’ eye-roll – even if that reaction turns out to be unwarranted, as in this particular case.

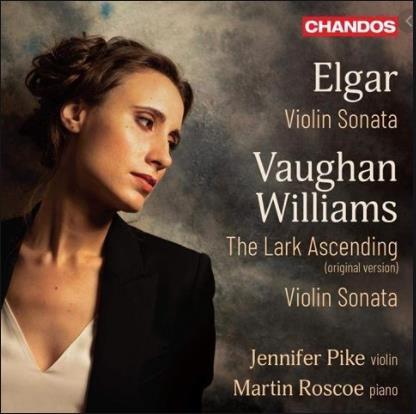

The headline in question read, ‘Jennifer Pike announces new album featuring the original version of Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending for violin and piano.’ My initial reaction was to the words ‘original version’, without registering ‘for violin and piano’ – a crucial error, when that original 1914 chamber version is a gem which stands as a completed work in its own right. The trouble, though, is that often ‘original version’ recordings refer to a manuscript that was subsequently revised by the composer – and for good reason. Yet now, as the rise of historically informed performance collides with the question of how to make your core repertoire recording stand out, these lesser-quality versions are being dusted off and put on disc. I do understand the need to stand out, and I admire the desire to explore core repertoire from a different angle. The trouble is that not all these first versions deliver entirely good music.

Take the 1844 first version of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, which has popped up a couple of times on disc now. Mendelssohn made fairly substantial amendments to his first manuscript before the 1845 premiere, some at the suggestion of his soloist, Ferdinand David, and some of his own. These encompassed a range of things from tempo markings and ornamentation to the register of the violin writing, plus orchestral adjustments, and they were all for the better.

Likewise, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto – the Vienna critics weren’t wrong to say after its 1806 premiere that ‘the endless repetitions of a few common passages may easily become wearisome.’ Beethoven knew it too. So, while from a scholarly perspective Christian Tetzlaff’s recording of the first version is an interesting listen, for pleasure alone I’ll go for one of his two recordings of the revised version, published in 1808.

An even stronger example is Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, which was premiered in 1904 but which the composer withdrew for reworking. Leonidas Kavakos’s recording of the 1904 version is noteworthy on an academic level, especially when it’s paired alongside the 1905 rewrite. But guess what? The original really did need some serious tightening up. It sags.

Read: Opinion: From the Heart

Read:Opinon: Wise words

Read: Opinion: Mind the gap

Essentially, I can’t get on board with resurrecting versions of works that were rejected by their composers on quality grounds – not least because the composers themselves would be turning in their graves. To make a journalistic analogy, I’ve been known to file an article only to rewrite it 24 hours later, having decided I can do better. So would I want The Strad to publish a first version nevertheless, arguing that my original intentions are more authentic? Hell, no!

Still, if an artist can make a convincing musical argument then it’s different. For instance, Viktoria Mullova and Patricia Kopatchinskaja have both recorded the Beethoven Concerto with inserts from earlier figurations, and they’ve done it so selectively and sold it so well with their playing that the changes make an impact without resulting in an inferior piece.

An even more solid example is the Schumann Cello Concerto, published in 1854. I can’t be the only critic who wonders whether Schumann really intended it to be such a pig of a piece to perform – as though the cellist is fighting their way through a vat of treacle. So I’m in favour of Alban Gerhardt’s fluid tempos, based on research that Schumann’s original tempo was q=144 rather than the 130 he eventually settled on after his chosen cellist, Robert Emil Bockmühl, insisted that it couldn’t be faster than 96 to 100.

So original versions aren’t always a bad thing. It’s just that the reasoning has to be watertight. Oh, and Pike’s album is very good indeed.

-

This article was published in the November 2020 Dover Quartet issue

The American ensemble on recording a new Beethoven cycle and inspiring the next generation of chamber musicians. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Dover Quartet on Beethoven

- Julie Lyonn Lieberman on teaching different styles

- Italian maker Carlo Bisiach’s US connection

- Frank Peter Zimmermann on recording Martinu

- The teaching methods of cellist Leonard Rose

- The bow makers of Hollywood’s golden age

Read more playing content here

No comments yet