Thomas Martin has tried practically every hat, from orchestra principal to soloist, teacher and instrument maker. Katinka Welz meets the eclectic bass personality in this article taken from the Winter 2000 issue of our now-discontinued sister publication, Double Bassist

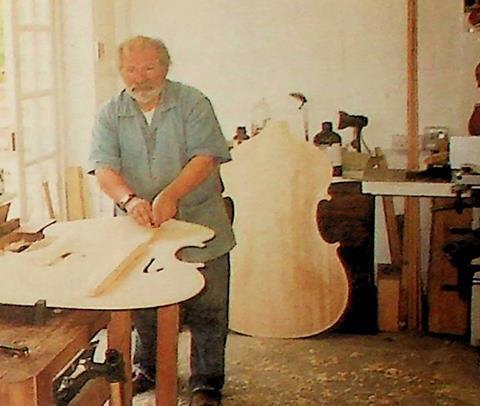

Thomas Martin’s home is a dream come true. The light, airy instrument workshop in the basement of the large house opens onto sun-drenched meadows, inhabited by a dozen horses. Three years ago, as their passion for horses led to a growing collection, Martin, his wife Jane and two of their four children escaped London to settle near Henley-on-Thames.

It’s been a long and eventful journey to this Elysium, and it’s far from over yet: at 60, Martin is as busy as ever, giving recitals, masterclasses, researching, collecting basses and - last but not least - making instruments. Earlier this year, his acquired expertise on instruments was credited when he was invited to judge at the Triennale Instrument Competition in Cremona, Italy for the first time.

Though from the old Philadelphia school and trained on gut strings, Martin is curious about all the latest developments in the bass world. ‘I try to keep up with it,’ he says, ’or if anything, ahead of it. I’ve tried, I think, to be a bit of a wave-maker always; to try and be in front. I don’t know if it’s my nature - could be.’

Born in 1940 in Cincinnati, Ohio into an old-fashioned, upper-class family, Martin enjoyed a cultured though formal upbringing in which music played a substantial part. ‘I was very keen on music.’ he recalls. ’I really wanted to do music, always.’

Martin picked up the double bass more or less by accident at the age of 12 when his junior high school acquired a new instrument and offered it to one of the students to play. Somewhat embarrassed about his latest hobby, Martin initially told his mother he was playing baseball while he was practising the bass at school. But as soon as his parents found out the truth, they arranged for lessons with the best bass teacher in town, Harold Roberts, with whom Martin studied in the Viennese tradition, playing German bow on gut strings. In his spare time however, the teenager jammed with friends, and even picked up the tuba for his jazz explorations.

The Martins got Tom his first bass, an old Bohemian instrument, from a certain C. David Horine, who subsequently opened the Bass Viol Shop in Cincinnati.

As his fascination with the instrument grew, Martin started to hang out at the shop after school, seeing instruments being made and meeting the leading bassists of the time, above all Ray Brown. ‘From that experience, I got this fascination with all facets of it.’ Martin reflects. ‘If I’m different from anybody else, that’s it. I wear almost every hat. and I find them all fascinating, still.’

In 1958 Martin got a scholarship to go to the Eastman School of Music, Rochester to study with Oscar Zimmerman, and although he found Zimmerman to be a ‘good musician’ , the young player was desperate to study’ with his idol, Roger Scott. When Martin passed the audition at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, however, his father, who did not agree with his son turning his hobby’ into a profession, did not allow him to go.

The frustrated young musician ended up quitting Eastman after just one year and got a job at the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, close enough to Rochester and Eastman for him to continue his lessons with Zimmerman on a private basis. Martin lasted two seasons with the Buffalo Philharmonic, but did not find them very rewarding: ‘They [the seasons] were horrible, it was like US$120 a week for 24 weeks - that was the job.’ So during the summer, he supplemented his meagre income with dance band tours and various freelance jobs.

Although the finances weren’t right, there was one great advantage to the job. On learning that the orchestra’s new bassist was merely 19 and had never finished music college, conductor Josef Krips decided to take him under his wing: ’He said. “I will be your school.’ Martin remembers, ‘and he was!’

Krips coached Martin outside sessions, teaching his young protégé everything there was to know about music. Everybody thought I was brown-nosing the conductor, but I wasn’t,’ Martin stresses.

From Buffalo Martin went on to join a Service Band in Washington. A second scholarship finally enabled him to study with Roger Scott, so he commuted to Philadelphia for his lessons on a regular basis. During the next three years, Martin was to receive an, in his words, ’unbeatable’ education from Scott.

‘My teacher [Scott] told me “I think you could be an orchestral principal. I think you should do that, I think you are good enough,” Martin says. And so we worked toward that. He moulded me in that way.’

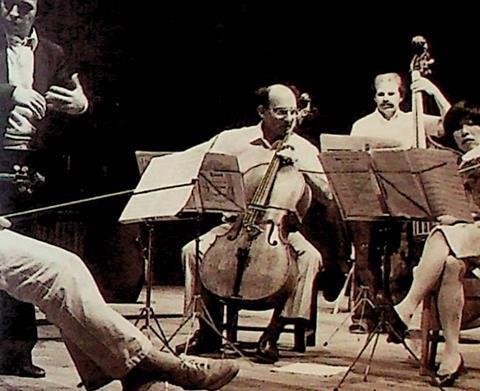

The education paid off, and in 1964 Martin walked straight from the Service Band into the position of co-principal with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra under Zubin Mehta, turning down a position as principal with Stokowski at the Houston Symphony Orchestra for financial reasons. Shortly after, when Martin had just settled in and even started to learn the language, his first wife decided to go back to the States. ‘I went to the boss, Maestro Mehta and said: “Zubin, my wife has left!” Martin recalls. ‘He said: “Are you happy?” I said, “I’m not sure.’”

Mehta advised him to return to the other side of the pond and audition for the principal post with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra. Martin did and got the job. but his marriage proved to be beyond repair.

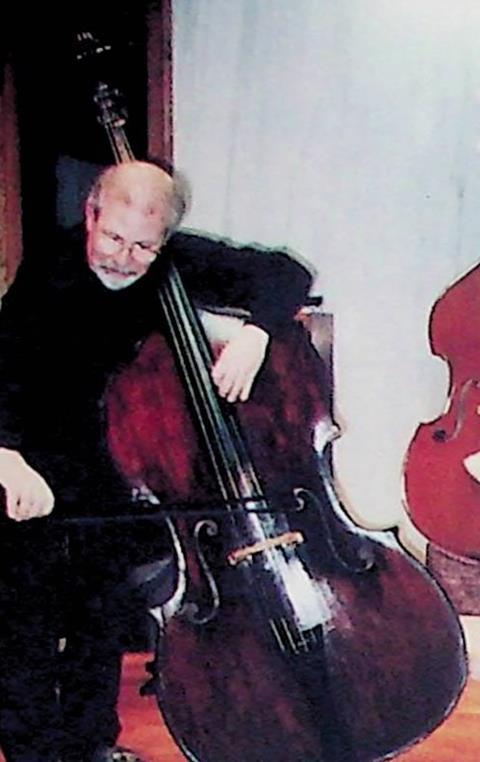

In 1972 Martin was ready to move on from the Montreal position and emigrated to the UK to take up the post of principal bass with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO). He remained with the LSO until 1976 and returned for another six years in 1990. In between, he worked with the English Chamber Orchestra and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and also began to develop his career as a soloist with the help of a long-dead master: Bottesini.

’When I was 40, my [second] wife bought me a record of somebody playing Bottesini, Martin recalls. ‘I’d never played it, and I listened to it and I said: “You know, I could do better than that!” So she threw down the gauntlet and said: “Why don’t you!” Nobody really plays this stuff right in my opinion. So there started the most exciting period of all.’ Martin decided that the only player to teach him could be the master himself, so he settled dowm with an old edition of Bottesini’s method and spent weeks going through every fingering and exercise in the book, trying to understand the whole other concept of harmonic playing of those days.

‘There are basically two ways a musician can approach music,’ Martin asserts. ‘One is the superimposition of himself on the composition; the other approach is: “How would this music have been played?” — so the superimposition of the music on the musician. That’s my way.’

Martin was hooked and started to collect everything by, and related to. Bottesini that he could lay his hands on, assembling a huge collection of letters, cuttings, scores and instruments, incessantly trying to complete his picture of the man and his music. I’ve had the most fun you can imagine learning the bass, being taught by somebody that died in 1889,’ Martin enthuses. ‘I tried to do it his way - then you think operatic style of the Italian 1800s. It wasn’t just the bass playing aspect of it.

‘The problem with most people that play [Bottesini] is that they can’t get beyond the bass to the music. That’s a job in any composition of course, but especially in Bottesini, which is very technically difficult. There is a challenge - make it sing. If you can sing it you are in with a chance, in my opinion.’ Martin’s labour of love paid off: he gave recitals all around the world, recorded all of the master’s works and made a name for himself as a Bottesini expert. But it was not just the Bottesini revival that benefited from Martin’s acheivements: ‘I’ve ended up, in a way, in the vanguard of the technical advance on the bass - having been taught by Bottesini! I’ve made big technical waves. I’ve played things on the bass, pushed things being played on the bass, that just nobody would have dreamt of.’

Read: Bottesini’s 200th anniversary: The world at his feet

Martin is keen to pass this experience on and leaching has always been a substantial part of his career. For the last 26 years, he has been teaching at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama and helped fill the front end of orchestras all over the country with students of his. Of late, however, he has become frustrated with the lack of financial support for music in the UK and prefers to give masterclasses abroad: ‘The arts aren’t well supported [in the UK],’ he criticises. ‘I still play and do masterclasses, but I never do it in this country at all. I only go abroad.’

He has also reduced his teaching post at the Guildhall to one day a week, but finds it difficult to really nurture the students on this basis: I would like to have kids play for a term on gut strings,’ he says, ‘but if you float in once a week and get paid by the hour, you just can’t do that.’

Playing on gut is an important issue for Martin, not least because of his experience with Bottesini. ‘Those of us who are my age understand the bass with gut strings and know what a different instrument it is now; And I think, those of us who played on gut strings - which I did until 1970 - know what the bass can and cannot do in reality. Because things are possible with steel strings that aren’t in reality. I don’t think they [today’s students] understand exactly what it can do and what it can’t.

‘When you played on gut strings, there were some people that had magic and many that didn’t. Now everybody’s got magic - the strings make it for them. I find it’s a fascinating thought, being from my generation.’

However, when Martin reduced his teaching activities he didn’t go into well-deserved retirement, despite having suffered severe heart problems over the years. Instead, he devoted more time to his expanding lutherie business. He had always been interested in instruments and over the years assembled an extensive collection of old and valuable basses, enriched by the legacy of his second father-in-law, bassist Ernest Ineson. This has now become what Martin calls a ‘revolving collection’, with Martin restoring an instrument and then ‘passing it on’ to another player. Some, such as his Bergonzi, also fetched record auction prices.

He found that each bass was a new challenge to restore and get to know: ‘Each one tells you something, each one tells you why it works or doesn’t work, and it tells you why it sounds like it does.

’I shouldn’t say this, but the bass I liked best was one of mine,’ he admits with a glint of pride in his eye. I guess since it’s “my thing’’ that I’m putting into them, they are the ones I’ve enjoyed playing most.’

Martin started making basses almost two decades ago, when German luthier Horst Grünert was looking for new models. Martin showed him his collection of old instruments and thereby ‘helped him develop most of his present models, in return for which I found myself in the bass making workshop.’ Weekly lessons in the UK with Andrew Dipper, a former professor at the International School of Violin Making in Cremona, followed.

Martin’s first basses were created with Grünert’s help, and the luthier was pleased with his new assistant’s progress. ‘Martin built his first eight instruments here,’ says Grünert. ’He had a good knowledge of instruments and knew what was important’. And Martin enthuses: ‘My second bass was a killer’.

Over the years, Martin’s business has grow from a small studio in his lounge to a workshop with two full-time staff, Ian Shankland and Robert Wright. Wright, who has been assisting at Martin’s workshop since 1999, is an expert on different woods. ’I am to woodwork what Tom is to music,’ Wright says. ’I understand woods intimately.’

Most of the work is shared between the three of them, and since Martin is also looking after the business side of the workshop as well as pursuing his performing career, he needs reliable assistants. It’s team work. We work together to make it as efficient as possible.’ Wright says.

‘We have areas which we stick to and others where we overlap. I bring up the instrument from the back, while Tom is doing the belly,’ he explains. ‘I always do the neck and always put the fingerboard on. I’m doing this work because I’ve been doing it for longer and have more of a feel for it. Tom always does the bridge and soundpost.’

Though it’s been 20 years since he made his first instrument and he’s made 46 basses since. Martin finds there is still room for improvement. Remembering his former tutor Dipper, he sighs respectfully: ‘The man was a varnish genius. I wish I was him, because I keep wrestling with varnish tones.’

Maybe once he has solved all the mysteries of instrument making, he will have time to devote himself fully to his horses; he is even hatching plans to start breeding them. One thing is for sure; this man will never fully retire. ‘My life has been finding targets and shooting at them,’ Martin muses. ‘Whenever I’ve reached a goal, I move on. I guess I’m cursed with this artistic restlessness.’

Thomas Martin plays a 3/4 Martin bass. His favoured bows are Reid Hudson and Michael Dolling. He uses D’Addario strings.

Read: The Venetian double bass: Venetian splendour

Double Bassist magazine: ‘Bottesini had no equal on the contrabasso’

- 1

- 2

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Double bassist Thomas Martin: Man for all seasons

No comments yet