Solo performer, orchestra member, teacher, conductor – most string players juggle roles. Sarah Mnatzaganian talks to some portfolio musicians to see how they do it

This article was originally published in the August 2006 issue of The Strad.

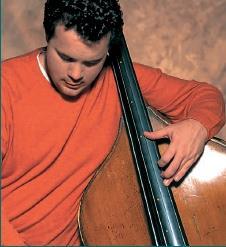

Edgar Meyer

Bassist and composer

I think what I do is incredibly normal. Since childhood I’ve wanted to have my own voice, and one aspect of that has been to develop many musical facets, including composition. I wanted to make sure that music would interest me for the whole of my life, that it would be a means to explore multiple possibilities.

My main reason for being in this profession is my love for 18th- and 19th century classical music, along with jazz and bluegrass and many other forms that are alive and still evolving this century. It’s natural for a bassist to embrace many different musical styles.

Probably my favourite playing situation is to play a mix of original music with like-minded people, without strict rules and boundaries. I like having musical conversations with the people around me and being able to learn from them.

It can be overwhelming to consider all the things I do in a year. I usually have two or three big recording or composition projects on the go, plus a regular set of concerts, and I try to schedule them all in a manageable way. Sometimes I’m too optimistic and take on too much, and I always spend much longer than I should completing my compositions.

As time goes by I’m becoming more successful at deciding exactly what I’d like to do and not just letting things happen. My latest project is something I’ve wanted to do for years: a solo album recorded alone in my music room, playing my own compositions on a range of different instruments using multi-track recording. I enjoyed it even more than I thought I would.

Paul Silverthorne

Solo violist and principal of the London Symphony Orchestra

One of the rewards of being a violist is that you can perform an enormous range of music if you’re open-minded and adaptable. Early in my career all my time was taken up playing with the Medici Quartet, so when I left the quartet in 1983 I was free to concentrate on more solo playing, as well as to explore the contemporary music field with the London Sinfonietta and commission a series of works for solo viola.

I’m not on stage as a soloist every day of the week – there’s not enough viola repertory for that – so I have to psyche myself up for different ways of being as I move between solo playing, the Sinfonietta and the LSO. I’m very lucky in that nearly all the work I do I find stimulating. When returning to orchestral playing I do sometimes catch myself in the wrong playing state and I have to be careful not to stand out too much.

But it always feels wonderful to be part of an orchestral organism again – it feeds one musically just listening to the other players. In some ways, performing in an orchestral section is harder than being a soloist, particularly if you have a pithy little solo passage to project into the auditorium before you disappear again into your section.

I’m also acutely aware that if I fall below the standard, there are about a hundred other people whose performance has been marred by it – not just me. I sometimes ask myself: if I needed to change direction, what would I drop? And I decide I’ll stay as I am – though I’d love to do more teaching!

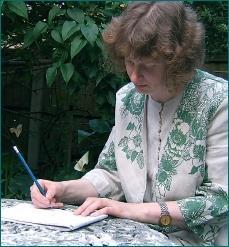

Rachel Stott

Composer, teacher and violist

I can’t imagine working full time as a teacher, composer or player – it just wouldn’t suit me. For ten years I divided my time between composition and freelance playing, but it wasn’t ideal.

I’d take manuscript paper on tour but there was never time to get down to any serious composition. Peace and space are essential for writing, and if your head is full of the music you’re performing it’s difficult to compose. Eventually I decided to limit my playing work to a few chamber ensembles and I developed a private teaching practice at home to create a regular income.

It’s an ideal combination: even if I’m working flat out to a deadline, I can’t compose all day without a break. By teatime when the pupils arrive I am ready for some distraction. Children’s demands are so immediate and they’re so cheering and amusing that it’s impossible to think about my composing work while they’re here.

Although the teaching is tiring, it’s not always draining. I compose for the children all the time – pieces for workshops, quartet arrangements or studies – and my youngest pupils often come up with such fresh responses to music that they give me ideas for composition. The playing I do nowadays is a positive luxury and a real source of inspiration. Hearing other players making a fantastic sound or expressing something wonderful musically often inspires me to write something in response – so I’d never want to be an ivory-tower composer.

David Finckel

Cellist and co-artistic director of Music@Menlo and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, New York

When I first joined the Emerson Quartet my solo playing had to go on hold while I learnt the quartet repertory. A few years later I formed a duo with Wu Han and discovered that my understanding of the solo repertory was hugely improved by my chamber music experience. My playing of the five Beethoven cello sonatas, for example, was transformed by having performed the 16 Beethoven string quartets with the Emerson Quartet.

Playing concerts is the most important thing I do, but you can’t have the instrument in your hands all day. You have a choice of how to spend the time when you’re not playing.

Nine years ago Wu Han and I were on tour in Switzerland when we were asked to direct a festival in southern California. We talked all through the next night as we drove over the Swiss mountains, and by morning we knew we had to take the festival on.

We’ve been running music festivals together ever since, fitting in the work between our concert schedules. When you’re a performer you have almost no control over your environment and we relish the opportunity to bring together all the ideas we collect on our travels and put them into action.

I come home from tours with suitcases full of brochures and my head full of the ideas I’ve gathered while performing. One recent project has been Music@Menlo, a chamber music festival in California’s Silicon Valley. Pessimists doubted that we could attract a new audience from the local tech industry to a serious music festival, but we have already had three sold-out seasons, with a fourth season taking place in August of this year well on its way to selling out, and the process has become a passion. So even when the cello is not in my hands, I still feel I am working in the service of music.

Stephen Bingham

Violinist and head of strings at the Colchester Institute

Some players might feel that it’s a luxury to have a musical career focused on one thing, but I find that I thrive on variety. The constant thread throughout my career has been leading the Bingham Quartet, but I have also taken on other roles and explored musical styles that I would never have thought possible when I graduated.

Ten years ago our quartet recorded some Boccherini quintets with jazz flamenco guitarist Jason Carter. I was intrigued that he played mostly by ear whereas we relied on the score. Discovering that I had recently bought an electric violin, he invited me to make a world music recording with him.You might imagine that swapping between acoustic and amplified instruments would be daunting, but getting used to my sound via an amplifier instead of under my ear proved the only real difficulty.

The rewards are considerable: playing in different musical styles is exhilarating and this experience has refreshed my interpretation of classical repertory. I now spend a good proportion of time performing an eclectic mix of acoustic and electric violin music, a selection of which I’ve recently recorded for Duplicity, my first solo album.

Becoming head of strings at Colchester Institute was another unexpected development. Fortunately, running the department has proved to be no more complicated than organising my own freelance career.

I’d have struggled at Colchester if I’d always had an artistic manager looking after my paperwork! Keeping admin under control allows me to focus on teaching and supporting the students. I try to make myself very approachable: although I’m only in Colchester part time, students can contact me whenever they need help. The rewards go both ways: it’s satisfying to see students progress, but teaching and mentoring also encourage me to think afresh about my own approach to music.

Reference

No comments yet