Have you ever thought about how much you will spend in total over the years to keep your instrument in working order? Drew McManus spills the beans, and then counts them

This article was first published in the December 2011 issue of The Strad, but many of these costs have remained fairly stable.

I’m not a string expert. I can’t differentiate between a Stradivari and a ‘del Gesù’. But after nearly two decades of working with orchestral string musicians and their employers, and being married to a professional orchestral violinist, I’m confident that I know far more about the dollars and cents they put into their instruments than they do. And I can say with the utmost assurance that they spend a great deal more to equip, maintain and repair their instruments than most of them realise. A lot more.

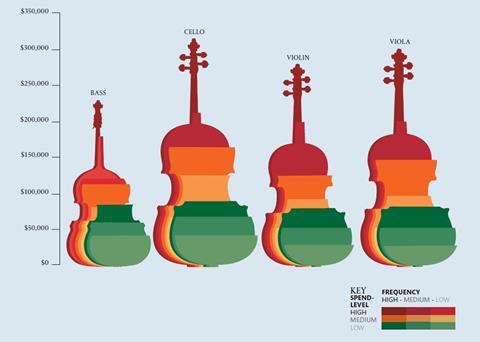

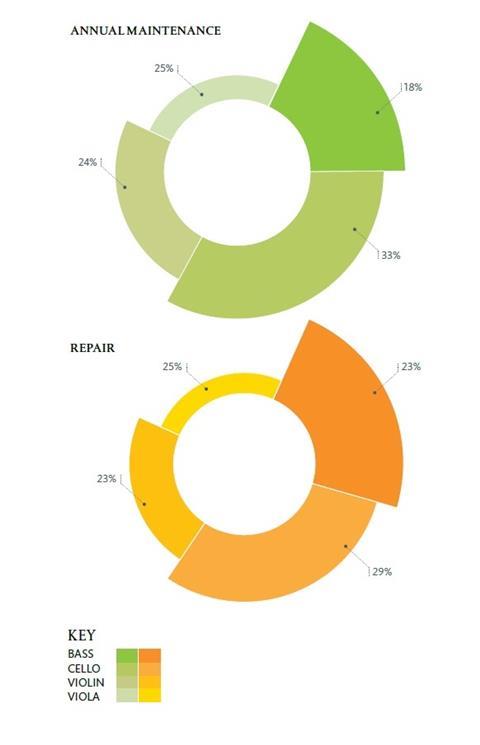

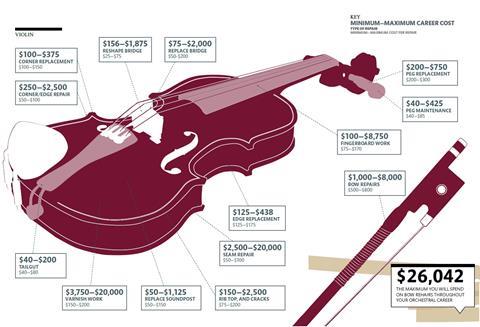

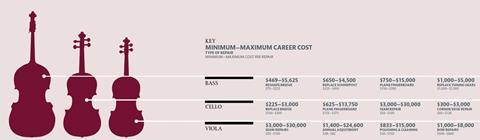

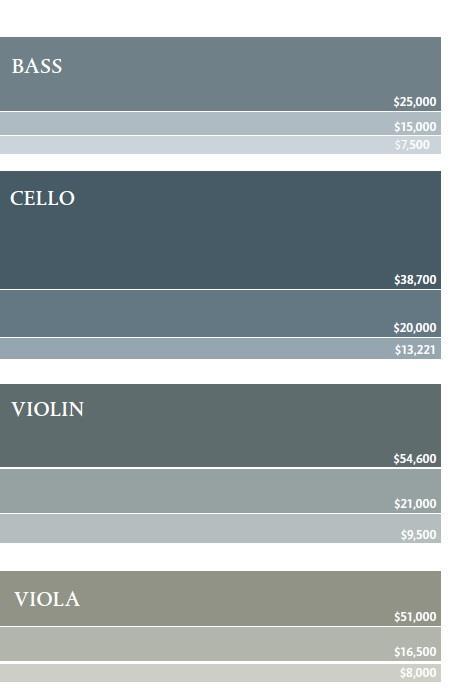

Nevertheless, it is extremely useful for players to calculate how much they spend on supplies such as strings and bow rehairs, along with expenditures for maintenance and repair. It helps them appreciate the costs they are expected to absorb over the course of their career. As a result, they can have a better sense of how much money they contribute to maintaining their skills and have less apprehension over asking for a fair wage. The following charts and graphs help illustrate not only how far these costs reach into musicians’ wallets but also provide necessary context to effectively manage the financial aspects of their career. In short, where you play, how you play and your attitude towards care and maintenance have a profound impact on your career costs of ownership.

Who we asked

In the course of gathering data, I spoke to more than 70 orchestral musicians, luthiers and repair professionals from a diverse cross section of points in their respective careers, who are based in the US , UK and Germany.

Musicians included section, fixed-chair and principal players from the violin, viola, cello, and double bass sections of professional symphony orchestras. Musicians who spend their careers working predominantly as soloists, chamber musicians or teachers have not been included.

Luthiers and repair professionals included 24 individuals who are owner-operators as well as those from multi-employee shops. Bow repair and rehair specialists were included in this group. Interview subjects were selected from as broad a cross section as possible of regions and climates within each location to account for the many variables that determine overall costs and frequency of shop work and supply purchases. Likewise, the musicians ranged from those using contemporary instruments and those using something made before 1900.

How to understand ranges

During the course of gathering data, it became clear that everyone maintains very personal opinions on these subjects. As a result, it is important to remember that this survey isn’t intended to produce a single figure or narrow range for the cost of ownership over the length of a career. Instead, the data is presented in a series of spend-levels: low, medium and high.

These are determined by a variety of factors such as location, type of instrument, cost differentials and even a musician’s personal attitude. This can have a dramatic effect on the total career spend, if we take a career as lasting 50 years. For example, a violist who changes their strings at the higher rate of frequency (twice a month) but purchases strings at the lowest price point will sustain approximately 53 per cent lower costs than a violist with similar frequency habits, but who purchases strings at the highest price point.

A stitch in time

Nearly all of the luthiers and repair professionals agreed that musicians who bring their instruments in for regular maintenance and inspection end up having fewer instances of costly repairs. ‘I like to think of it like diagnosing cancer,’ said one repairer. ‘The earlier I can catch something like a crack, the more likely it is that I can correct the issue before it develops into something that will require me to remove the top or back, and that’s where the real risk and costs are incurred.’

This attitude appears to be confirmed by the musicians as well. Those who say they follow their luthier’s recommended maintenance schedule reported lower instances of high-priced repair work. On the other hand, some musicians knew they were playing a riskier game, but their options were influenced by location as well as attitude.

The cost of climate change

Among the items included in this research, the one thing every luthier and repair professional agreed on was that climate has the greatest impact on overall maintenance and repair. Musicians who perform in climates dominated by exceptionally low, high, or highly variable humidity and temperature can look forward to higher-than-average costs.

How many professional musicians remain in a single area for the bulk of their career? Not many. Tours, summer festivals, and working for ensembles scattered over the world conspire to ensure that professional string players are going to pay the cost of their own type of climate change.

One of the by-products of this phenomenon is an increase in some of the more expensive repairs such as cracks and warping. ‘It doesn’t matter if your instrument is one or several hundred years old. Moving in and out of different climates for as little as a single day can do all sorts of nasty things to an instrument,’ said one luthier with more than 30 years experience.

It pays to get the best

Next to weather, luthiers and musicians confirmed that the majority of their most costly restoration and repair work relates to correcting poor repairs. One luthier and repair professional with more than 50 years’ experience lamented what he defined as a shortage of first-class luthiers who are willing to go into the service end of the business. He explained: ‘There are plenty of talented people who want to make instruments, but not enough who want to do go into the less glamorous restoration and repair side of the business.’

Another repair professional with nearly the same amount of experience expanded on his colleague’s observation. ‘Education is certainly better than when I started in the business. There are many more schools turning out much better instrument makers than in previous decades, but those people aren’t taught about restoration and repair,’ he said. ‘This means there aren’t enough experienced repairers around and too much maintenance and repair work ends up getting done by people who don’t have enough knowledge or experience. I spend so much time undoing that sort of damage.’ Several restoration and repair professionals stressed the importance of developing long-term relationships as the best measure against costly repairs.

One retired repair professional who went into the field after a career as an orchestra violinist explained, ‘I’ve been on both sides of the fence and I can’t recommend strongly enough that each musician should seek out the finest repairers they can find,’ he said. ‘More damage is done to fix bad work than all of the accidents combined.’

Most of the luthiers and repairers I spoke to said that they have a sliding scale for some of their rates based on the length of their relationship with a client and the value of the instrument.

What the numbers don’t include

It’s important to know what we didn’t include in the analysis that could still be considered an accessory, supply, maintenance or repair.

Clearly, cases are associated with the actual instrument almost as much as the bow. But of all the accessories a string player can purchase, the decisions and needs associated with purchasing cases include enough variables as to make it counter-productive to include them here.

Differences in insurance costs based on the value of an instrument worthy of being used in a professional orchestra can be extraordinary. Moreover, there is a distinct difference between orchestras that may or may not provide instrument insurance as part of employment. The result is a very uneven application of costs that musicians may be expected to absorb. Neither of these elements is trivial and the reader should be aware that they are expenses that are above and beyond those catalogued in this analysis.

All costs are quoted in dollars but were gathered in the UK, Germany and the US in 2011.

No comments yet