The Japanese violist recalls how playing Mozart’s Symphony no.40 under Pablo Casals proved a life-changing experience and gave a vivid insight into the mind of a master musician

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

In 1966, in my first year studying at Juilliard, Felix Galimir invited me to Vermont to participate in the Marlboro Music Festival. I didn’t know what to expect, and the first thing I saw when I got there was a huge board with the schedule for the whole week written out. I discovered my first rehearsal was the very next day, with three people I didn’t know, to practise Smetana’s String Quartet no.1, which I also didn’t know. I quickly discovered that it starts with a viola solo, and the viola part is huge from beginning to end, so I stayed up until 3am that night practising it. That was my first introduction to Marlboro, but I loved being thrown in at the deep end and being expected to swim! That summer I had no time to think, and I loved playing chamber music so I just embraced it.

I was part of the Marlboro Chamber Orchestra, which contained some of the finest young musicians in the country at the time. Conducting the ensemble was cellist Pablo Casals, who I looked up to as a kind of god. We played Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony and Mozart’s Symphony no.40 – another piece that was new to me, and which I found difficult because of the amount of spiccato.

I think Mozart is probably the most sensitive of composers, and also the most entrancing: if you don’t have that feeling of fascination about his music, it’s impossible to play it properly. In that way, it has to be connected to your soul, otherwise it’s meaningless – like when you read a book and realise you haven’t taken anything in. Every note is leading somewhere, so that you know what’s happening four bars later: it gives a feeling of destiny to each piece. When you have that, you find there are so many different ways to play it, but everyone has to have their own particular feeling about it. If a student can’t understand that, they should find some easier, Romantic repertoire, until they’re ready for Mozart.

It was an education to watch Casals conduct. He wasn’t particularly concerned with details, but he was brilliant at imparting the spirit of the music into all of us. I’d never experienced a chamber orchestra this way before – it felt as if we were in a boat together, rising and falling with the waves of the music. Casals seemed to have a kind of impulse, an organic vibration that balanced all the disparate parts of the orchestra. I still remember that sensation, which I’ve carried with me throughout my life – that feeling of musical impulse is very important to bring musicians together, and it’s something that the great artists can communicate so well. I had the same feeling when I played with Sándor Végh. I’m sure everyone felt the same; it was somehow like a big orgy of music making, all communicating together on a deep level.

Casals was revered by everybody at Marlboro. I never found him someone I could talk to as a friend – and not very many people could – but he was excellent at communicating his musical feeling to us all. Later on, I went to the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico, which attracted a lot of great musicians: Barenboim, du Pré, Barbirolli, all wanting to perform alongside Casals. It’s festivals like that and Marlboro, with a plain and simple ethos of just making music together, that brings it closer to your soul and gives you a base to work from.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

Read: Nobuko Imai: Life Lessons

Watch: Nobuko Imai gives viola masterclass

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

-

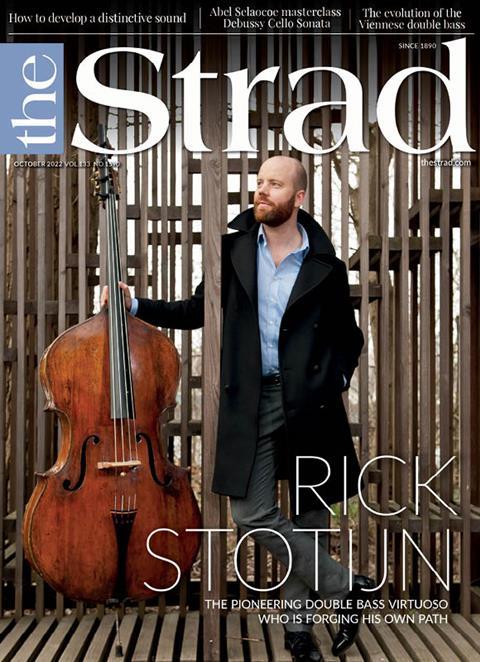

This article was published in the October 2022 Rick Stotijn issue.

The Dutch double bassist is on a continual quest for original repertoire for his instrument. He tells Kimon Daltas about his new album and collaborative work. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Rick Stotijn

- The Viennese Double Bass

- Scottish Fiddle Dance Music

- Rachel Barton Pine

- Developing your own sound

- The Strad Calendar 2023

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet