In theory, it is possible for a student to gain their ABRSM Grade 8 having only learnt 24 pieces in their life. Davina Shum argues that such a quantified approach to learning is no way to become a rounded musician

My days of preparing students for grade exams, often at the behest of pushy parents or schools, remind me of a scene in Spring Awakening. In this musical, set in 19th-century Germany, precocious teenage rebel Melchior Gabor writes furiously in his journal, despairing about his school’s obsession to measure one student’s ability against another, saying: ‘The progress of the students reflects back only on the rank and order of the faculty.’ Without spoiling the plot, this approach ends up having devastating effects.

I used to teach a student who didn’t practise and I very much got the sense that he played cello ‘just because that’s what you do’. His mother approached me after he scraped through his Grade 1 cello exam. Ignoring the fact that he scored a low pass, rather than take any opportunity for reflection and improvement she said, ‘It’s great that he’s got his Grade 1, but we need to get him to Grade 5 as soon as possible.’

A strangled cry escaped my throat, to which she replied, ‘He’s applying for secondary schools and to be eligible for scholarships, he needs to audition at Grade 5 level.’ Through gritted teeth, I asked when said audition would be. ‘In six months. If he can’t get the certificate by then, maybe he can just play the first two lines of a Grade 5 piece. Can you teach him two lines of a Grade 5 piece?’

I’m sure many music teachers have encountered a situation like this. Why do these circumstances continue to arise?

Students reach for that holy grail of Grade 8 just so they can say ‘I have my Grade 8’

You’d be hard pressed to find someone who would argue against the educational, social and mental benefits of learning a musical instrument – indeed, that’s why many children take up music lessons in the first place. Our educational structures, however, feel the need to measure these benefits with numerical quantitative units. Reasons for this include aiming for the top of the schools’ ranking lists, qualifying for scholarships, or meeting quotas for the powers that be. When institutions become occupied with box-ticking, they often forget the very essence of what they are measuring, and musical benefits are cast aside.

I understand the grade system is a useful way to structure a student’s learning; many students are motivated by a goal of an exam and work diligently towards that. Unfortunately, numerous other students (and parents) just see these exams as a way to unlock the next level and don’t realise they’re not really learning anything.

Blindly ignoring the fact that there is an enjoyable and fulfilling process that usually comes with learning an instrument, the parent described above was so fixated on the idea of Grade 5 that she was potentially setting up her son (and his teacher) for a thoroughly miserable time.

Quantified achievements are used by students, teachers, parents and institutions to compare themselves to others, often in a damaging way. When students are rushing between exams, fine details can get discarded, eliminating the opportunity for exploration and consolidation of musical development. Many students are constantly reaching for that holy grail of Grade 8 just so they can tell others ‘I have my Grade 8’. There is a difference between a student who rushed through the system having only learnt 24 pieces in their education journey, with cavernous holes in their musical knowledge, and one who took the time to enjoy the process and develop into a well-rounded musician who will continue to flourish.

We need to relish the joy of music making and instil this approach with our students. By having a tailored, adaptable method of teaching, we can ensure that we are raising not only the next generation of musicians, but music lovers and appreciators who look back on their days in the teaching studio with fondness, rather than resentment.

-

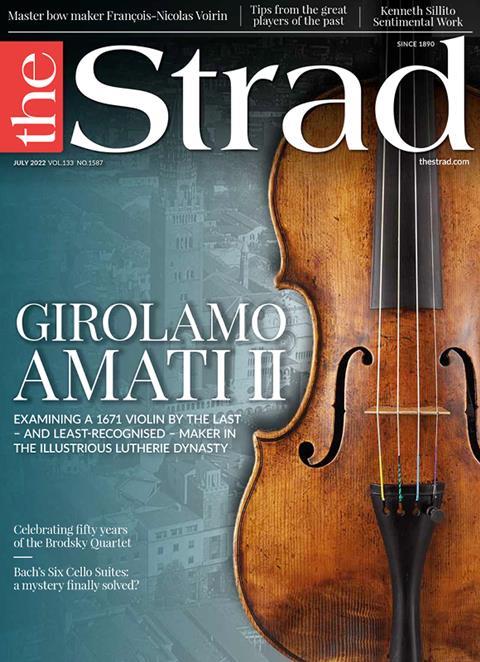

This article was published in the July 2022 Girolamo Amati II issue .

The last of the Amati dynasty was an almost exact contemporary of Stradivari. Barbara Meyer examines one of his early instruments, alongside one from 1719. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Girolamo Amati II Violin 1671

- Brodsky Quartet at 50

- Bach Cello Suites

- Heath Quartet Session Report

- Lost arts of string playing

- François-Nicolas Voirin

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet