Performing Benjamin Britten’s 1931 String Quartet in D major for the composer was an eye-opening experience for the former leader of the Gabrieli Quartet

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

In 1974 I was summoned with the other members of the Gabrieli Quartet to the Red House in Aldeburgh, where the 61-year-old Benjamin Britten had requested our presence. We were shown into the rehearsal room, where there were four music stands laid out with handwritten parts for Britten’s 1931 String Quartet in D major, a piece we’d never seen before. Britten had composed it while he was still a student; apparently his tutor Frank Bridge had criticised it, saying the second movement was rambling, although the composer John Ireland had liked it. It seems that he’d heard it performed by the Stratton Quartet in 1932 and then, like many other pieces, stuffed the manuscript in a drawer and forgotten all about it.

We had about an hour to learn this 19-minute quartet without Britten there. We liked the first and last movements, although we had to agree with Bridge about the second – there were moments that reminded me of playing Purcell fantasias, where you’re never quite sure if you’re in the right place! The first movement has quite a strong motif that reappears at the end of the third, which is a typical jiggy English-style piece, and quite fun to play. Then Britten came in, switched on a reel-to-reel tape recorder and asked us to play it for him.

Read: Book review: From the Leader’s Chair by Kenneth Sillito

Read: Edgar Francis wins Cecil Aronowitz International Viola Competition

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

It was quite nerve-racking, especially since Britten’s writing for strings is so demanding. He had an amazing knowledge of stringed instruments and their capabilities, and he was extremely clear on how his works should be played. I remember when leading the English Chamber Orchestra, the violist Cecil Aronowitz was flying up and down the fingerboard, basically on one string, and Britten told him: ‘That’s not right – stay in position and use different strings.’ No other composer would have that attention to detail. Even when I first met him, when I joined the ECO, he gave the impression of being a rather strict master of a school, precise and clear in everything he did and said. There was never any feeling of ‘trying something out’; it had to be done his way from the start. So performing for him after an hour’s rehearsal time was not easy.

After we’d finished, he didn’t look very happy. We asked how he felt about it, and he said, ‘It sounds like someone else’s music. Can you hear my voice?’ We all agreed we could, but he still seemed unhappy with it. Still, he agreed to our playing it at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1975, and then recording it a year later at Snape Maltings concert hall. We also performed it at the University of Essex, where we had a residency in the 1970s and were always looking for different works to play for our regular audience, along with Britten’s other ‘official’ quartets.

Around 20 years after we’d played it for Britten, I was on tour with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields and pianist Murray Perahia. I was recounting the story of this rehearsal and impromptu recording by the composer, and how he’d asked if we could hear his voice. Murray nodded and said, ‘That’s right – I was there!’ It turned out he’d been quietly sitting at the back of the studio while we were rehearsing and playing; we were dimly aware of someone else there but hadn’t paid any attention to him. He’d been there to rehearse for some recitals, as accompanist for Peter Pears, and he also said that he’d then spent the whole of his lunch break convincing Britten that his voice really could be heard in that quartet. I think this turned the tide in the quartet’s favour – after that he also agreed for it to be published for the first time in 1974, with a few revisions, as well as letting us perform and record it. It was incredible that Murray, then aged 27, had managed to rescue the quartet, and helped make it known to the world.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

Read: Sentimental Work: Roger Tapping

Read: Sentimental Work: Arnold Steinhardt

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

-

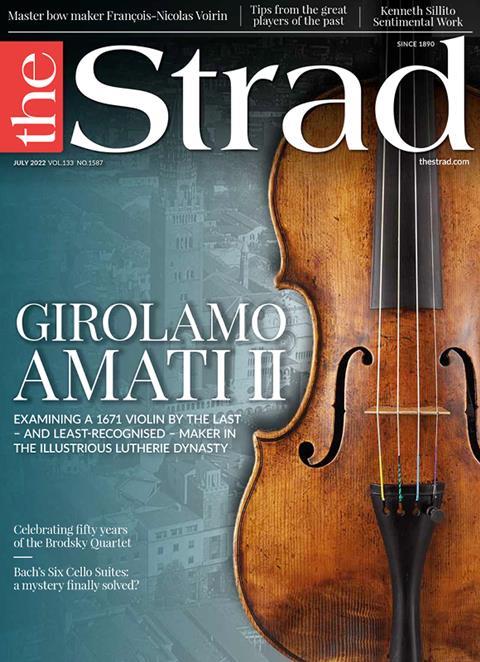

This article was published in the July 2022 Girolamo Amati II issue .

The last of the Amati dynasty was an almost exact contemporary of Stradivari. Barbara Meyer examines one of his early instruments, alongside one from 1719. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Girolamo Amati II Violin 1671

- Brodsky Quartet at 50

- Bach Cello Suites

- Heath Quartet Session Report

- Lost arts of string playing

- François-Nicolas Voirin

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet