Kare Eskola reports from Helsinki on 2022’s emotionally charged International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition, the first to take place for seven years

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

There was only one topic of discussion among the audience after the finals of the International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition 2022: Dmytro Udovychenko and his exceptional interpretation of Shostakovich’s First Concerto. The competition’s location in Finland (next to Russia), the war in Ukraine, the Russian-born conductor Dima Slobodeniouk and the 23-year-old Ukrainian violinist playing such raw, blood-tinged, universal music created a magical combination, arguably containing more musical meaning than anything else in the competition.

The day after the performance, my colleague, who directed the competition television broadcasts and had heard far too many violin concertos by any standards, commented on social media: ‘It is hard to get over this Shostakovich.’ Even my sound engineer colleagues, after a violin-heavy workload of two weeks, told me that never before had it been so silent among the studio crew.

‘An absolutely unbelievable interpretation,’ said jury chair Sakari Oramo privately after the prize ceremony. ‘It proves that such magnificent music is timeless and deals with things that cannot be put into words.’ In my books, that performance alone was quite an achievement, even for a prestigious music competition with a history that goes back to 1965.

Read: ‘Every day there is something new’: Pekka Kuusisto on the c.1709 ‘Scotta’ Stradivari violin

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

It was also an achievement that the Sibelius Competition happened again after a postponement of nearly two years due to the pandemic. And as the competition is held only every five years, this meant that the last edition took place as long ago as 2015. The atmosphere in 2022 was exceptionally energetic and full of excitement, which was probably also down to the event being held in late spring (18–29 May) rather than the usual early winter (November–December). The instruments clearly liked this and didn’t misbehave (with one unlucky exception in the first round), as did the competitors, who could actually escape their practice rooms and explore outdoors. This time the obligatory visit to Sibelius’s home Ainola surely revealed to the competitors that there is a lot of natural light in the composer’s concerto, not just ice and eerie northernness.

Among the Finnish audience, I couldn’t detect the kind of collective frenzy there was in 1995 when Pekka Kuusisto won. It didn’t help that this time the three Finnish early-round competitors didn’t make it to the finals, the reason for which luckily was clear to everyone. On the other hand, the competition reached more people than ever, thanks to the excellent streams and broadcasts by Yle (the Finnish Broadcasting Company).

Remarkably, there were only a few Covid absentees. Jury members Nam Yun Kim and Tong Weidong could not attend, but in their place was a playful experiment with artificial intelligence: Oramo had been teaching a computer program how to play Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, based on performances by previous winners and finalists, and the program gave its own judgement after the finals. Personally, I think that AI should start with Twinkle twinkle, little star, like the rest of us, but in the end it fared surprisingly well.

Clearly there is still some serious lack of courage with choosing repertoire for violin competitions

Other notable absentees were the two pre-qualified Russian competitors, Ravil Islyamov and Galiya Zharova. Originally, they were allowed to participate, even after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but in early April the competition committee reconsidered the matter and excluded them ‘in order to protect other competitors and the competition as a whole’. In the Finnish media and among the audience there was surprisingly little discussion about the exclusion. The delicate ethical question was taken bluntly as some kind offorce majeure.

The rest of the narrative in Helsinki was familiar. In the first round the usual selection of Bach, Paganini and Sibelius miniatures revealed that some competitors were ready, some were interesting, few were neither and even fewer were both. In the second round there was plenty of room for the competitors to create a proper recital with personal programming, but only Diana Adamyan took the opportunity to think outside the box to her advantage, playing Baghdasaryan’s Rhapsody from her native Armenia. Clearly there is still some serious lack of courage with choosing repertoire for violin competitions.

In my opinion, the most notable player not to make it to the finals was Qingzhu Weng from China. His interpretations were not petrified by the endless hours of practice; the music seemed to take its shape in the here and now – even the Bach in the first round and especially Ravel’s Tzigane in the second round. Otherwise, the selection of the six finalists was uncontentious. Adamyan, Udovychenko, Yesong Sophie Lee (US), Nathan Meltzer (US), Georgii Moroz (Ukraine) and Inmo Yang (South Korea) were all up to the task. The eventual and very clear winner, Yang, however, had for the first round chosen Ernst’s Grand caprice on Schubert’s Erlkönig, which seemed hubristic to me, as he could not tame the frightening creature, and in the second round his playing felt occasionally more artistic than musical. But in the finals, he changed my mind. His Sibelius Concerto was immaculate, with an exceptionally fast and fluid finale. He played with a big, crisp, clear sound on the c.1718 ‘Bostonian’ Stradivari that he has on loan.

Technically, perhaps the most intriguing thing that stands out about Yang might be his bow hand, as his pinky and thumb look very stiff. Perhaps it proves that there still is some wiggle room in the mould of young violinists, though it definitely worked for him, as he swept the board with the €30,000 first prize, €2,000 special prize for the best performance of Magnus Lindberg’s commissioned Caprice, some mentoring sessions from Oramo and Kuusisto, the loan by Jane Ng (through J&A Beare and Beare’s International Violin Society) of a fine 1772 Guadagnini violin made in Turin, and a few concert dates to boot.

The second prize of €20,000 (plus a product prize from Finnish audio electronics company Genelec Oy) went to Meltzer, with his thick, sweet and American sound. Here we have a contemporary version of Itzhak Perlman in the making. Udovychenko, with his Shostakovich still in everybody’s mind, was only third (€15,000), but perhaps that was for the best. After all, the Sibelius Competition 2022 is not the Eurovision Song Contest, and now I don’t have to raise my eyebrows at a statistical wonder: two out of two pre-qualified Ukrainians made it to the finals, but only one out of ten Koreans. Whether or not this was due to unconscious bias on the part of the jury, it was ultimately Udovychenko’s extraordinary Shostakovich that proved that the music really has a meaning, even in competition, and despite the cultural structures behind that meaning not being universal.

Read: Sibelius Competition winner gets his hands on a Guadagnini violin

Read: How do you prepare for a concerto competition?

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

-

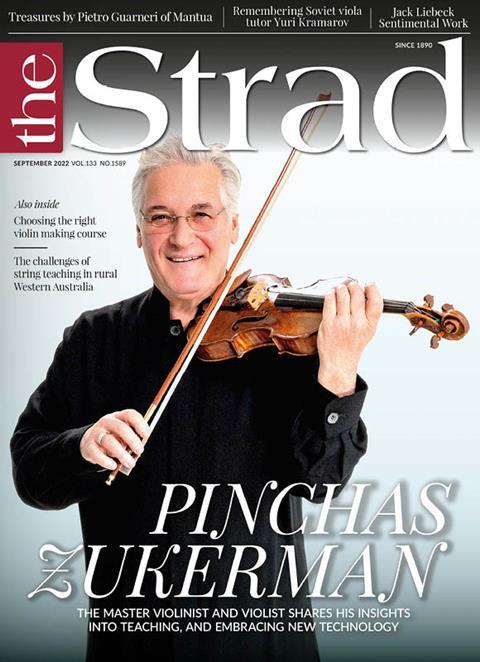

This article was published in the September 2022 Pinchas Zukerman issue.

The veteran violinist and violist tells Pauline Harding his views on everything from his new masterclass series to the role of technology in string teaching . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Pinchas Zukerman

- International Lutherie Schools

- Newark School of Violin Making

- Strings in regional Western Australia

- Villiers Quartet Session Report

- Pietro Guarneri of Mantua

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet