Murray Lerner’s 1979 Academy Award-winning film documented the beginning of Isaac Stern’s enduring legacy in China. In this article from the August 2016 issue of The Strad, Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the documentary’s stars about the ‘Stern effect’

The year was 1979. Emerging from decades of isolation and political turmoil, China had just opened its door to the West, and legendary violinist Isaac Stern was hoping to peek inside. The result was the Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, which chronicles Stern’s visit to music conservatoires in Beijing and Shanghai. This brilliant, touching film gave Westerners an insight into life behind the Bamboo Curtain, while igniting Chinese careers and changing music in China for ever. The Stern family has continued its association with the country, but it is China that will never forget. August 2016 sees the start of the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC), which organisers hope will help to inspire and motivate a new generation of musicians.

Isaac Stern had long used his musicianship to build bridges and foster talent, touring the Soviet Union in 1951, helping save New York’s Carnegie Hall from destruction, and mentoring a host of promising young players including Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma and Pinchas Zukerman. While some claimed his extra-musical efforts were hampering his own skills, music and humanity were, to him, simply extensions of each other. China opening up to the West was his next logical frontier.

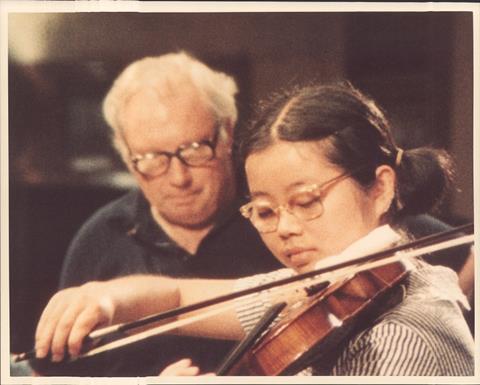

However, when even US diplomat and close friend Henry Kissinger couldn’t help him gain entrance, Stern had a strategically casual dinner with China’s foreign minister, and an evening conversation became an official invitation. The film was also a product of family friends, but the Sterns insisted it be about China, not them. ‘Even when I see it today, that’s what impresses me; it was so unpretentious,’ says David Stern, whose clear admiration for his father still resonates. ‘It wasn’t a grand master delivering the word. My father had lived a life that very few people can live, and all he wanted to do was share it.’ Directed by Murray Lerner and featuring pianist David Golub, the film primarily follows Stern’s work at the Beijing and Shanghai conservatoires, although the family did observe a Peking Opera rehearsal, a variety show and a gymnastics training school, as well as hear Chinese traditional instruments. But Stern always saw his work with students, instructors and orchestral players not as teaching but as sharing the music that had shaped his entire life. ‘We always talk about music as a global industry, or as a way to unite cultures, and a lot of it is nonsense,’ says David Stern. ‘But in this case it was true.’ In his view, the film’s key moment comes when Stern tells young violinist Ho Hong-ying to put her bow down and sing the music to make an emotional connection, and then try again. ‘It was what he believed, and he was sharing it with kids that hadn’t experienced it at that level,’ says David. ‘He was telling them they were all capable.’

The Chinese, of course, saw his visit differently – and understanding why might need some context. China had experimented with classical music during the early 20th century but political upheavals such as the Chinese Civil War and the Japanese occupation interrupted any serious study. When Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China in 1949 he followed the Soviet example in agriculture, industry and the arts: the theatre and ballet academies and music conservatoires established in the 1950s were in the Soviet model, a pattern that to some extent continues today. Students played Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff but had little exposure to Mozart and Bach. Then, in 1966, the Cultural Revolution criminalised all Western influences. Chinese artists – and audiences – were limited to what became known as the ‘eight model operas’, or yangbanxi, which were five revolutionary operas, one cantata and two ballets. This period only ended with Mao’s death a full decade later.

And just three years after that, Isaac Stern arrived. Many felt this was not simply exchange, but rather an angel of music descending from on high, a cultural rainfall on a long-parched land. Now a renowned soloist and professor, violinist Vera Tsu was a Shanghai Conservatory of Music sophomore when she played a transcribed Chopin nocturne and a Saint-Saëns piece for Stern, a moment captured in the film. ‘He was like a god,’ she gushes, as enthusiastic 37 years later as if it were happening today. ‘We didn’t know anyone could play like this; the tone and colour he produced, it was so pure, so sweet, with so much variety – it was from heaven.’ She also revelled in the masterclasses, saying these kinds of instructions about interpretation were all new to them. ‘His visit was a tornado for the Chinese music scene – not just for the students but for the teachers too,’ she says. ‘We suddenly knew there was another world, and we started thinking we should seek out some real music.’ A founder member and first violinist of the Shanghai Quartet, Li Weigang was one of two high-school students to join Stern’s masterclass with some of China’s then best-known soloists, who played in front of 1,500 professional musicians from around the country. Scheduled to go last, Li sat in the (then-unfamiliar) air conditioning for two hours, and grew increasingly nervous while waiting. ‘When I stood up to play, my legs were visibly shaking.’ But whereas the others were stopped after a few minutes, Li was not only allowed to finish but Stern even asked for an encore.

‘His visit was eye-opening, to me and to other players, and even to professors; it was the beginning of a new era of music making in China,’ he recalls. Li feels Stern also influenced his playing style, in terms of his phrasing and his character – plus ‘Stern had one of the greatest bowing arms of any violinist.’ But most importantly, he says, ‘Stern taught us that you don’t only play the violin – you make music with it.’

One star of the film was cellist Wang Jian, then a nine-year-old wearing socks with his sandals and a red ‘Young Pioneer’ scarf, the Socialist world’s youth uniform. To him these concerts were not unusual; newly open China was hosting a stream of dignitaries, and Wang was always trotted out to perform – he was once criticised for yawning while the future queen of Cambodia held him in her lap. But while he wasn’t exactly sure who Stern was, he couldn’t help but notice him. ‘He was wearing orange (unlike China’s muted tones), his glasses were on top of his head, and his face was red like a lobster,’ he recalls. ‘He looked very weird to me.’ As he began playing he heard Stern’s voice, then suddenly the film crew rushed up to arrange lights and cameras. ‘He told them to film me,’ says Wang. ‘And at the end he shouted, “Bravo! Bravo!” The Chinese never say those things; even the Europeans never shouted like that,’ he remembers. ‘I was really happy.’ Unlike the other featured musicians, From Mao to Mozart directly launched Wang’s career: with the help of executive producer Walter Scheuer and Detroit businessman Sau Wing-Lam he secured a place at Yale and received the 1622 Nicolò Amati cello that he still plays. But in the meantime, Stern validated Wang’s unusual playing style. Teachers were constantly correcting his bow position, or pushing him to play more technically demanding pieces, but Wang had learnt differently, from another master who was cut from Stern’s cloth. ‘My father taught me that it’s better to play simple pieces meaningfully rather than complicated pieces without meaning,’ he says. ‘We were always criticised. But after Isaac Stern’s visit I could feel the difference; the way I played was accepted.’

Wang is certain that Stern brought about a seismic change in China’s music scene. ‘He showed us, he told us, he demanded from us that music was all about expressing yourself,’ he says. ‘The content is more important than the presentation – and in those days in China, presentation was everything.’ China had talented teachers, he recalls, but the general trend was to study the form and imitate the West. ‘We did not have the confidence nor the tradition to say that music is only a tool to express yourself,’ he recalls. ‘Isaac Stern said, “I don’t care how you play, but you have to say something.”’

‘My father was one of the few who managed to elevate everyone around him,’ says David Stern, ‘whether it was a conversation in a restaurant or playing a violin concerto.’

But perhaps the best takeaway is Isaac Stern’s address at the end of the film: ‘If you do not think that music can say more than words, that there can be no life without music; if you do not believe these things, then don’t be a musician.’ Says David Stern of his father’s advice, ‘It’s the strongest defence of arts I’ve ever heard.’ Words to live by indeed.

This is an edited version of an article which appeared in The Strad’s August 2016 issue – download the full magazine on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

No comments yet