Technique advice, exercises and repertoire examples from Lionel Handy, cello professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London, Birmingham Conservatoire and Winchester College, UK

It is impossible to fake good double-stops. If there were a shortcut to playing difficult concertos without practising them, it would have been discovered a long time ago. Unfortunately there is not, and to play them well requires constant diligence. The way each of us fingers double-stops is very personal. The unorthodox can become orthodox if we aren’t imprisoned by convention: we should experiment and do whatever we need to do to express the music well, without encumbrances. Below I explore some ideas for fingering 3rds and 6ths, inspired by violinist Albert Sammons’s book The Secret of Technique in Violin Playing (1916), which I have recently transcribed for the cello (see box, page 79).

EXERCISES

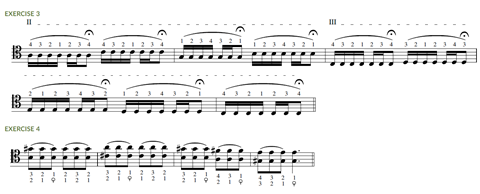

Start by playing broken double-stops beginning on an up bow. This way the double-stop falls on a down bow, giving you slightly flatter hair and making it easier to get a good sound. Play the key note (for 3rds, the lower note; for 6ths, the upper note) first, followed by the second note of the chord, then both together. When you are more confident, move to half-broken scales: play the first note alone, then add the second as a double-stop. Finally, practise the double-stops together, unbroken.

PRACTISING 3RDS

I have developed a system of what I call ‘half-fingered 3rds’: climb up using thumb –3, thumb –2, thumb –3, and so on. In the lower register of the cello, most players use 4 –1 for every 3rd; they only finger the 3rds using the thumb higher up the fingerboard. The thumb is stronger than the fingers and can also be used to great effect in the lower positions. Traditionally cellists have an aversion to using the thumb below the halfway harmonic, but it is far stronger than the fingers.

Exercise 1 uses the usual fingerings for 3rds. It is the cor anglais solo from Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony, which I’ve transposed into G major to make it easier to check the intonation – also the reason for the left-hand pizzicato to end.

Playing the broken 3rds in exercise 2 will be difficult at first, but this fingering sounds cleaner than shifting both fingers for each 3rd.

I call exercise 3 the ‘Bluebottle’, because you have to play the same notes with different fingers, which Sammons said sounded like a fly trapped in a jar. This should be practised very slowly at first, for absolute accuracy of intonation. Gradually increase the speed.

PRACTISING 6THS

6ths are usually easier to play than 3rds, as the left hand isn’t put into extended positions. Exercise 4 is excellent for developing left-hand accuracy, fluidity and shape.

REPERTOIRE

3RDS IN MUSIC

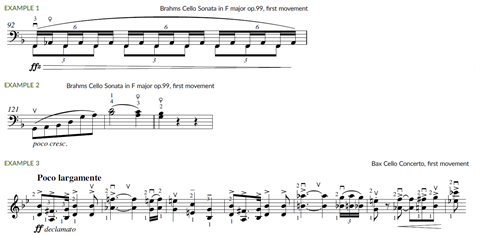

In example 1, this F–A flat tremolo is often fingered using 4–1, but play it with 3–thumb instead. It is easier, particularly if you have small hands, and the sound will be stronger. In example 2, the music can sound smudged if you use a 1– 4 fingering. Try semi-fingering it for a more legato effect and relaxed hand position.

6THS IN MUSIC

When playing 6ths in pieces, we need a different approach from when we are practising exercises. If we have to play a scale in 6ths high up the fingerboard, we usually hop across the strings using a succession of 2–3, 1–2 fingerings. This works fine on the violin, where the spaces are smaller and the strings closer together, but on the cello it can create a gap, which disturbs a good legato.

In example 3, I get around this problem by using a 1 on the lower note and alternating between 2 and 3 on the upper note. This means that I never have to jump across the strings, and it frees up the hand.

I often make my students play the ferocious passage of 6ths from the third movement of Schumann’s Five Pieces in Folk Style op.102 (example 4), fingered in a way that means they don’t have to hop across the strings. Remember: ‘Thou shalt not hop within a slur’ – at least, not unless you really have to.

Another example comes from the Walton Concerto, in the fourth bar of figure 4 in the first movement (example 5). If you were playing a simple G minor scale in 6ths, you would use the fingering 3–2, 2–1, 3–2, but here you can keep your first finger on the D string so that a true legato with no jumps can be achieved.

IN YOUR PRACTICE

If you don’t have time to practise very much, the most important thing to play every day is double-stop scales – especially 3rds, 6ths and octaves. Do these both with standard fingerings and with the more experimental ones explored in this article.

Double-stops are hard work, but they are vital for improving hand shape and intonation. Build them into your routine, alongside ordinary single-note scales and arpeggios, diminished and dominant 7ths, and a study. Popper is particularly useful (see box).

TIPS FOR TEACHERS

React to each student individually. Don’t be imprisoned by convention. For example, if you see a G above middle C with a double-stopped lower note, try using different fingers rather than an automatic fourth finger. Bear in mind that the second and third fingers are the strongest, with the best balance; if playing 5ths, consider an alternative to barring across the strings with one finger, which produces too much tension. Encourage students to experiment and do what suits their body shape; help them to find out what makes the strongest sound.

This article was first published in the June 2016 issue of The Strad

Interview by Pauline Harding

1 Readers' comment