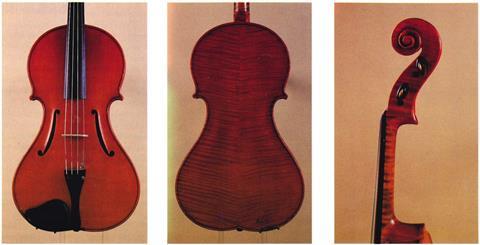

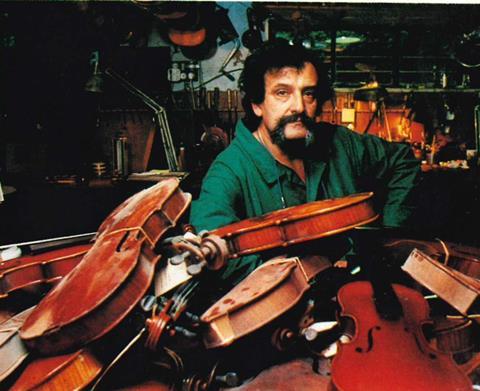

This photo of an experimental viola design was included in an article by Shmuel Segal in the October 1991 issue of The Strad on the Weinstein workshop in Tel Aviv. Amnon Weinstein has more recently been noted for his ‘Violins for Hope’ project

Amnon Weinstein was born in 1939, just at the time Moshe [his father, also a luthier] was thinking of setting up his shop. When interviewing Amnon, I suggested that it must have been only natural to follow in his father’s footsteps, but he would have none of this: ‘There may always have been a tradition in Europe for luthiers’ sons to become luthiers themselves, like the Hills in England and the Steiners in Germany, but when the Jewish pioneers emigrated to Palestine at the beginning of the century they were intent on breaking with every tradition and rebelling against anything which reminded them of their European exile. My father did this initially, as you know, and in a strange way this rebelliousness has continued into the second generation as well, the result of which was that in my youth I never even dreamed of taking up my father’s profession.’

In his high school years Amnon became a wood sculptor, studying it very seriously at the AVNI Institute of Decorative Art for three years. He exhibited his sculptures while he was at school and afterwards, describing his reviews as ‘more than favourable’. At the same time he was studying the viola, something that could not be avoided in the Weinstein household. Because of his family background, when he was recruited into the army at 18, he was asked not only to play in the Israeli Army Symphony Orchestra but to maintain all the orchestra’s instruments. He continues the story:

By the time I was released from the army, I had three years’ experience of instrument repair so it then occurred to me to take it a little more seriously. I heard that there was a new school for violin making in Cremona, applied and was accepted as a student. But I must stress that I never let my studies there interrupt my sculpting and jewellery design and I continued to take part in exhibitions in Italy.

He studied violin making with Professor Guiseppe Ornati and Ferdinand Garimberti but the one who influenced him most was Professor Pietro Sgarabotto – ‘an extraordinary person, a pedagogue, an artist. Today, now that I teach young students, I always hold him before me as a model teacher.’

Near the end of his studies he decided to become a violin maker, but only after he had undergone a complete change of attitude towards the art of lutherie: ‘I realised that violin making is an art and not just a craft, because you cannot explain why two violins which look exactly the same have such different sounds. This decision may sound on the surface revolutionary but to me seems perfectly natural. My definition of a violin is now a “sculpture which creates sound”. So, in a way, I am still a sculptor, but now just in one area.’

After four years in Cremona, he graduated and returned home. He began to work with his father but also to experiment on his own. A year passed by. It was 1969 and the violinist Isaac Stern arrived in Israel, bringing with him the renowned French violin maker, Etienne Vatelot. The purpose of Vatelot’s visit was to find a young Israeli student to come and study with him.

‘To my immense joy, I was chosen. So off I went to Europe again for a year. What I learnt from Vatelot was an expertise in restoration techniques, things that I had not learnt in Cremona. In time, we became friends and now we still have our weekly conversations, the distance between Paris and Tel Aviv proving no obstacle.’

He returned home a great deal more experienced which gave him a new status in his father’s workshop. He began to deal with nearly all the repair work, while Moshe worked on the bows and his ‘children’s’ welfare. By this time he had developed what he calls his ‘credo’ as an artist:’ Because, as I said before, violin making is an art and not only a craft, it does not matter if I copy the instrument of an Italian maker, the outcome will be my own creation, for better or worse. I use as a starting point a violin by Guarnerius which belongs today to my friend Pinchas Zuckerman. I chose it because I saw it as a historical ‘breakthrough’ in the interrelationship between sound and shape. I feel that, as an artist, I can understand the principles of this instrument and I am now trying to develop these ideas in my own way.’

‘Speaking of design, I would like to mention my new model for a viola. As everybody knows, a viola is a very difficult instrument to play, and I think I have found a solution which will facilitate the way of playing the viola without affecting the quality of its sound. I combined design ideas of the 16th century (a Maggini viola) with the 20th century conception of sound. This viola has been made for Shlomo Mintz, so we will soon know if it’s successful, although it will obviously take time to settle and I will make adjustments.’

Amnon Weinstein in 2014 talks about the ‘Violins of Hope’ project

This leads us to the question of ‘setting up’ old instruments, about which Amnon has some very strongly felt ideas: ‘I do not believe there is a single violin which does not sound; but there are violins which are not adapted to their players character or which are set-up badly. Because in Israel there are so few good Italian instruments and yet so many talented players who need a good instrument I have been forced to obtain the best results from the most hopeless instruments. Setting-up is an art all of its own in which knowledge, skill, experience and intuition are mixed. One knows what to do, but whenever intuition and emotion are involved it is difficult to articulate a rational explanation.

In 1982 he took part in the Salt Lake City competition for violin making and won a gold medal for sound and a certificate for workmanship. He is keen not to appear to be over-confident, however: ‘When I think of the things I have been saying , you may get the impression that I am very pleased with myself and that I have no doubts. This is far from being the case. We have an old Hebrew saying, “You cannot be a prophet in your own home town”. You may be considered one of the best in the world but not in your own country. However, I am satisfied with my clients, which include Zuckerman, Accardo, Mintz etc.’

Since 1970, Amnon Weinstein has been permanently in Israel, but, like any other artist he enriches and refreshes his work by visiting makers and antique violins abroad. A creator does not stop learning and developing as long as he lives. In our days, when the world has become smaller and travelling is easier recharging ones batteries has become very simple. Although times have changed, I keep my father’s tradition alive. No young musician coming to our house for help will find a closed door.

‘Today, with the ever increasing numbers of emigrés arriving from Russia, amongst whom are many string players, I find myself preparing all the old violins I have in my stock for those who could not bring their instruments with them. We will give them as presents to enable them to continue their careers in their new country. What can I say? you cannot run away from your tradition. It is stronger than you are. History repeats itself and the wheel always comes full circle.’

No comments yet