The passing of Her Majesty the Queen marks the end of a historical era that saw seismic changes in all walks of life - not least the stringed instrument trade. In this article from 2012, Philip Kass examines how everything from manufacturing to trade in the Far East have all changed during that time

Discover more lutherie articles here

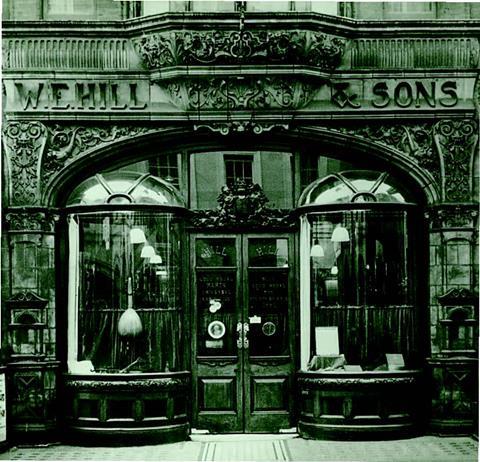

Although the UK may have been much diminished in the post-war years, it remained dominant in one field: the violin trade. The colossus that was W.E. Hill and Sons was still the base for the world’s foremost dealers and experts on fine old violins and bows, their status enhanced by the high regard in which they were held by the primary buyers of the day: Americans. Auctions in the UK, particularly Phillips and Puttick & Simpson, also continued to be the primary wholesale outlets for dealers from around the US and Europe.

But there was no mistaking where the violin money, and the sales, were to be found. The American market had well-financed orchestras and well-heeled musicians, the result of a demand generated by a long history of successful music education and these individuals and institutions would drive string sales over the coming decades. Musicians in the Philadelphia Orchestra (and many others) received interest-free loans to buy great violins, so even the rank and file could play on Guadagninis and Storionis. And the prices that American players were prepared to pay were far higher than those affordable by musicians in Europe: the result was a steady flow of the finest instruments to the US.

At that time, America had the world’s largest economy, making up perhaps half of global GDP. The country had suffered in the Second World War, but not on its own shores. In terms of the violin trade, it might have had the financial resources, but it had no Hills’ – although Rudolph Wurlitzer, William Lewis & Son, and Lyon & Healy, the largest US firms, had all established close links to the London dealers. Alongside these firms stood Emil Herrmann, then the leading dealer in classic Cremonese instruments, who had presciently moved his business from Germany to New York in 1923, well before the Nazis had come to power. These firms would soon be joined by three new names: Francais, Moennig and Warren. Jacques Francais had in fact chosen to work in New York rather than continue his family business in its historical home of Paris.

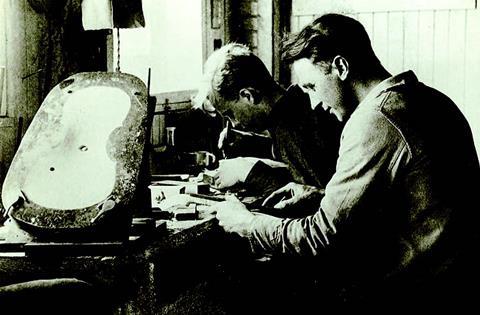

America was also on the verge of gaining a respect for its expertise similar to that of Hills’, thanks to two men: Rembert Wurlitzer, the heir to the Wurlitzer business, and the exceptional restorer Simone Sacconi, who joined Wurlitzer when Herrmann’s closed in 1950. Sacconi was an equally gifted violin maker, and he taught the craft to his apprentices and also encouraged them to develop their skills. Violin making in the US had mostly collapsed in the wake of the Depression (most of the New York shops had closed during the 1930s), but Sacconi’s teaching preserved the finest traditions of lutherie for a new generation. Today almost all the important US violin makers can trace their heritage back to him.

Read: Musical groundbreakers: female luthiers and their experiences in the lutherie industry

Read: Female luthiers: And justice for all?

Read: ‘Don’t be afraid to introduce yourself to people in the trade’: how to enter the lutherie profession

Discover more lutherie articles here

Turning to the string world’s commercial manufacturing sector, both of its traditional centres were devastated after the Second World War. Markneukirchen, the home of German violin making, was under first Soviet and then East German Communist control, and those in the trade who could do so fled to the west, rebuilding their businesses in towns such as Mittenwald and Bubenreuth. Mirecourt, the French centre, suffered an unexpected blow from a different source – a nearby American military hospital whose salaries dwarfed those of Thibouville–Lamy and Laberte. In time these companies recovered, but both French and German manufacturers also faced increasing costs that left them unable to fulfil their previous functions.

This situation continued until the late 1960s. By that time, several new variables were changing the equation. Western Europe had recovered from the war, and it had a long historical bond with classical music and violins, particularly in West Germany, its largest economy. The collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement immediately redefined exchange rates, to the advantage of West Germany and the disadvantage of America (as any US buyer of a Mercedes in those years will well attest). The impact on violin prices, not surprisingly, was immediate – for Germans, everything everywhere else was now available at a significant discount. Prices had been increasing, but now went up much faster as West Germans found their Deutschmarks bought far more than previously.

However, there was also a new entrant into the violin market: Japan. After years of reconstruction following its own devastation in the Second World War, the country had marked its revival with its own Olympic Games in 1964. Japanese musicians had been travelling to Europe and the US to learn Western music, absorbing it profoundly. They soon made up a significant proportion of students in Western conservatoires. The Japanese economy, driven by exports, was speeding past Germany to become the world’s second largest. Newly affluent Japanese, whose children were now playing Western stringed instruments, had the means to buy them the best examples. One of the few export bright spots for the US and Europe in those days was the steady flow of violins to Tokyo, at ever-increasing prices.

The moment when everyone realised just how much things had changed was the 1971 sale of the ‘Lady Blunt’ violin for $200,000. Although those in the trade knew that Stradivari prices had risen dramatically, to have the benchmark publicly raised by so much still stunned them – as did the identity of its purchaser, a Singaporean collector.

At the same time, other Asian nations began to gain prominence, both financially and musically. In South Korea, a generation had been inspired by the Chung family and increasingly opted to play violin, cello or piano, and Taiwan, similarly smitten by Western music, also had a thriving export economy.

One significant Asian country remained on the sidelines, however: China. While China had become similarly enamoured of Western music, it also had a long memory of national humiliation at European hands. And in any case, the Communist regime and the 1968 Cultural Revolution meant that even communications with the West, let alone commerce, were out of the question. The same, after a fashion, was true of the Soviet Union. Although its conservatoires produced a steady output of talented musicians, its political system dramatically hindered the ownership of classical violins, and travel restrictions made shopping expeditions nothing but a dream.

During the 1970s and 1980s, many of the players in the string dealing world left the scene: Lyon & Healy, Lewis and Wurlitzer had all closed by 1974. Hills’ closed in 1992. Prices continued to move in fits and starts, mostly following the currency of the strongest market, and the demand for fine instruments over the decades increased by at least a factor of ten. By the late 1990s, Stradivaris were routinely selling in dealers’ shops for over $1m.

Read: Lutherie in China: the enterprise system

Read: Violin making at Xinghai Conservatory of Music

Read: Violin making schools in China: The way of the future

Discover more lutherie articles here

London now looks out over a very different world. In spite of the 2008–9 crisis, which hit the UK capital very hard, its financial markets remain, along with those of the US, the world’s most important. In old violins, the names might have changed, but the dominance of London has not. The place of Hills’ has been taken by J.&A. Beare, and Phillips, now owned by Bonhams, has been joined by Sotheby’s and several other new auction companies, although nowadays they sell as much on a retail basis as they do wholesale.

In the US, the names have also changed, and although its arts are suffering a severe contraction, the size of its economy and the scale and breadth of its marketplace still make it one of the essential players in the global string trade. Countries such as Germany, South Korea and Japan, whose musicians helped drive up prices are now suffering population declines, which would not bode well for the market were it not for the enormous potential of China, newly rich and displaying that same hunger for Western music that drove Japan 50 years ago.

However, China is not yet a powerhouse in the old violin market. Instead, it rules in commercial manufacturing. Any feasible competition is overwhelmed by the millions of violins that the country produces, with a quality and a precision unthinkable in Mirecourt, Markneukirchen or Mittenwald, and at prices so low that they boggle the mind. Indeed, it remains to be seen whether Chinese manufacturers might not prove to be victims of their own formidable competence: at present rates, there could easily be a Chinese-made violin, viola and cello for each human being on the planet in a decade or so.

Although China’s government is still ostensibly communist, that ideology is just a memory in Russia. With freer commerce and travel in place, Russia is making itself felt in the fine instrument trade in a way not experienced since before the First World War. However, the prime impact of the country’s new-found wealth has been in the prices of the very best instruments, since its richest citizens have been able to pay whatever it takes to enlarge their collections. And once again, the ‘Lady Blunt’ has proven the bellwether for global instrument prices: as before, it was only reflecting trends in the market, but the public sale in 2011 for almost $16m of a benchmark instrument set an eye-wateringly high price for those not following the prices of violins. In 2012 the ‘Vieuxtemps’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ sold in a private sale for an even higher sum; it remains the highest price ever paid for a violin.

We have yet to see whether some of the world’s other rising economic stars, such as India or Brazil, will continue these trends. But on one matter we can be sure: violin prices and markets will carry on following international financial trends, just as they have over the past 64 years.

TIMELINE

1965

Hottinger Collection purchased by the Rembert Wurlitzer Company

1971

Sotheby’s sells the 1721 ‘Lady Blunt’ Stradivari for $200,000, a world record for a violin

1972

Simone Sacconi’s book The ‘Secrets’ of Stradivari published

1974

Founding of the Nippon Music Foundation; founding of the Violin Society of America; closure of the Rembert Wurlitzer Company in New York

1977

Founding of the Chimei Culture Foundation, Taiwan

1987

Exhibition of Stradivari’s work in Cremona, curated by Charles Beare

1988

The ‘Baron Heath’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ of 1743 becomes the first violin to be sold for more than a million dollars at auction ($1,059,344)

1992

Closure of W.E. Hill and Sons in London

1994

Exhibition of Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ violins at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, curated by Peter Biddulph

1999

Founding of online auction house Tarisio

2003

European auction business Phillips merges with Bonhams

2004

Founding of UK-based auction house Brompton’s Auctioneers

2011

The ‘Lady Blunt’ Stradivari sets another record, being sold for almost $16m by the Nippon Music Foundation

2012

The ‘Vieuxtemps’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, now played by Anne Akiko Meyers, sells for an even higher, undisclosed sum in a private sale

Read: 1721 ‘Lady Blunt’ Stradivari violin sells for £9.8m

Read: Violin making in Seoul: Gangnam style

Discover more lutherie articles here

No comments yet