- News

- For Subscribers

- Student Hub

- Playing Hub

- Directory

- Lutherie

- Magazine

- Magazine archive

- Whether you're a player, maker, teacher or enthusiast, you'll find ideas and inspiration from leading artists, teachers and luthiers in our archive which features every issue published since January 2010 - available exclusively to subscribers. View the archive.

- Jobs

- Shop

- Podcast

- Contact us

- Subscribe

- School Subscription

- Competitions

- Reviews

- Debate

- Artists

- Accessories

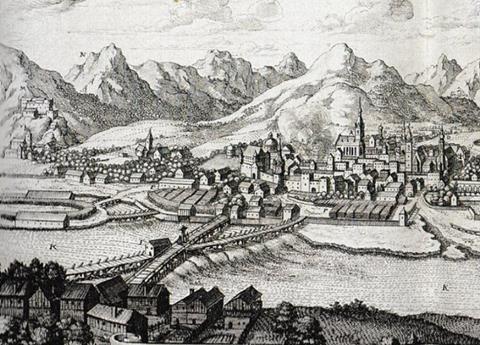

Jacob Stainer’s birth: A question of dates

For centuries, historians have tried to settle on a definitive birthdate for Tyrolean luthier Jacob Stainer. Heinz Noflatscher explains how we now have an upper limit for his birth year – and why researchers were foxed by the elegant handwriting of the master

Over the years, there have been many articles in The Strad concerning the master violin maker Jacob Stainer. The very first, published in November 1910, gave a short précis of his life along with a call for more research; this was followed by papers on specific Stainer instruments and his influence on future makers, among other topics. However, the most fundamental details of Stainer’s life have always remained shrouded in mystery: namely the dates of his birth and death. All we have known with any certainty is that he must have died in late October or early November 1683.

Stainer’s birthdate is even more mysterious: we have never been able to state the year of his birth with any confidence. These two questions have intrigued researchers for more than two centuries, having been discussed in specialist encyclopaedias, music literature and local history studies since the late 18th century. Recently, however, new evidence has come to light regarding Stainer’s birthdate: we now have a clear upper limit for his year of birth, a terminus ante quem.

In scholarly publications from around 1800 onwards, we find several different dates quoted as Stainer’s birth year: 1621, 1617 (or earlier), 1618, and most recently 1619. This last was the received wisdom just three years ago, when a conference took place in Innsbruck, near the luthier’s birthplace of Absam, to mark his 400th anniversary. Stainer has always been a renowned figure in musical circles: inventories of people’s possessions included references to Stainerische Geige (‘Stainer violin’) just a few years after his death, and his instruments were being copied – and his labels forged – even in his own lifetime. That said, his name seems to have been rapidly forgotten: he left no male heir, and his wife and three daughters died in poverty a few years after his death. This also accounts for the lack of a family grave, which would have been a perfect source for his dates. His name was also neglected by historians; he was mentioned in the late 18th century by Johann Friedrich Primisser in the well-regarded Tirolischen Chronik, but only to say that he lived as a famous violin maker in Absam in 1673 (Ruf 1872, pages 1-2).

Already subscribed? Please sign in

Subscribe to continue reading…

We’re delighted that you are enjoying our website. For a limited period, you can try an online subscription to The Strad completely free of charge.

* Issues and supplements are available as both print and digital editions. Online subscribers will only receive access to the digital versions.