- More from navigation items

- Home

- News

- For Subscribers

- Student Hub

- Playing Hub

- Podcast

- Lutherie

- Magazine

- Magazine archive

- Whether you're a player, maker, teacher or enthusiast, you'll find ideas and inspiration from leading artists, teachers and luthiers in our archive which features every issue published since January 2010 - available exclusively to subscribers. View the archive.

- Jobs

- Shop

- Directory

- Contact us

- Subscribe

- Competitions

- Reviews

- Debate

- Artists

- Accessories

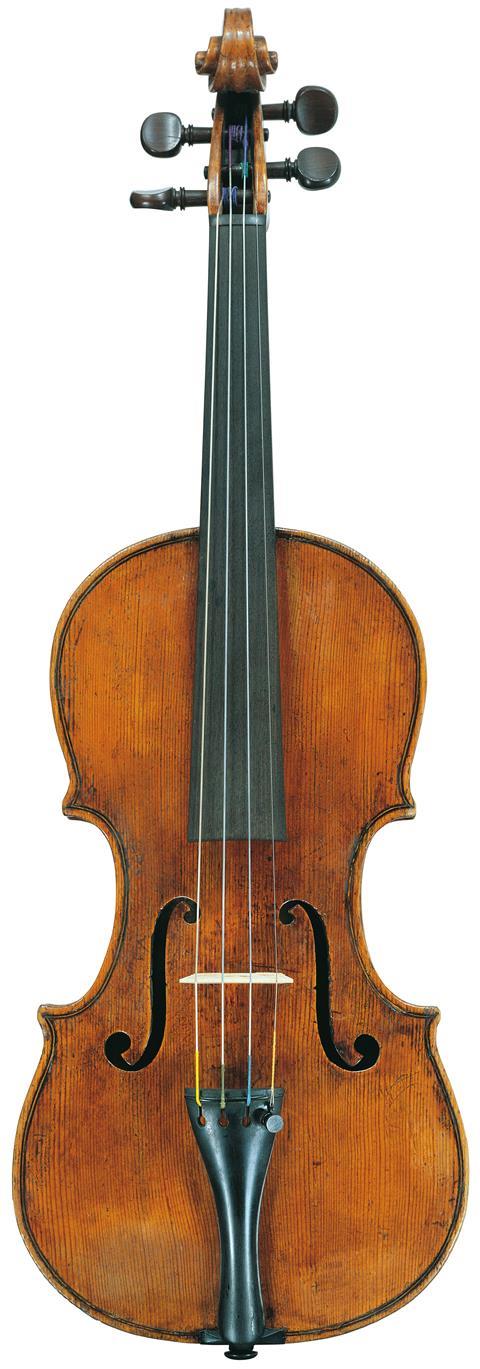

Luigi Cavallini: A maker in the rough

Tuscany in the 19th century was home to numerous luthiers, some of whom were carpenters who turned their hands to instrument making. Florian Leonhard examines the career of Luigi Cavallini, a lesser-known self-taught maker whose work, while unusual in parts, displays a surprisingly high level of craftsmanship

The golden age of violin making in Tuscany spans the whole of the 18th century. All of the region’s most influential luthiers worked during this period, and the start of the industry’s decline can be dated to the death of one of its most significant figures, Giovanni Battista Gabbrielli (1716–71). The work of these makers was concentrated on the dominant city of Florence as well as Siena, Livorno and Pisa, Tuscany’s predominant centres of commerce. But alongside the activity of such crucial instrument makers as Gabbrielli, we find an abundance of minor craftsmen, such as those living in the ancient city of Arezzo, in the Valdichiana area about 50 miles south-east of Florence.

This lesser-known Tuscan metropolis has long been a draw for artisans and is still an important centre of artistic heritage, with its Church of San Francesco boasting incredible early Renaissance frescos by Piero Della Francesca. Here, luthiers such as Pietro Ugar (c.1747–1819) and the little-known chitarraio (guitar maker) Jacopo Salvadori lived between the 18th and 19th centuries. Their period of activity was closely followed by that of Lorenzo Arcangioli (1825–74), the only luthier in the city who owned a fabbrica dedicated to constructing musical instruments in the second half of the 19th century.

In this period and context, fabbrica (‘factory’) indicates a place where specific items were manufactured; in this case it refers to the Arcangioli workshop. Arcangioli presented two examples of a violoncello da spalla at the last Tuscan Exhibition of Arts and Manufacturing, held at Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio in 1854. That same year, according to contemporary records, he employed three makers, producing high-quality wooden musical instruments, especially violins. We also know that Luigi Cavallini and two of his brothers moved to Arezzo around 1860, and they may have worked for Arcangioli.

Luigi Cavallini was born in 1828 in Monte San Savino, a historic town within the province of Arezzo. Here he lived until he moved to Arezzo aged around 32. He was a minor luthier yet a skilled one, although few of his instruments are widely known today. He was also the father and first master of the more famous instrument maker Ettore Oreste Maria Cavallini, known primarily by his second name Oreste (1868–1934). Luigi Cavallini was primarily afalegname; commonly rendered as ‘carpenter’, the term in 19th-century Italy could indicate a wide range of skills that also involved the making and restoration of stringed instruments. He moved to Arezzo when the city began to see the first changes that would affect its social composition. The city had been strongly tied to agriculture and had been marked by significant social immobility. Then, from the middle of the century, changes began to occur through the slow appearance of a middle class.

In particular, Arezzo saw the flourishing of a lower middle class, through merchants, artisans and employees, which led to the development of a third sector in a society hitherto comprised of nobles and peasants. This period also saw the emergence of a proletariat. However, rather than industrial development, the changing economy was more a matter of manufacturers, small factories and craft workshops, many of which were small and family-run. This is the context in which we have to consider the activity of Cavallini, who probably worked together with his brothers in the workshops of artisans such as Arcangioli until he set up his own.

Already subscribed? Please sign in

Subscribe to continue reading…

We’re delighted that you are enjoying our website. For a limited period, you can try an online subscription to The Strad completely free of charge.

* Issues and supplements are available as both print and digital editions. Online subscribers will only receive access to the digital versions.