John Dilworth muses on how a lutherie imperfection has become a defining factor in instrument appraisal

Discover more lutherie articles here

This article is from the November 2013 issue of The Strad

The pins I’m thinking of are possibly the violin’s smallest wonders. They are the tiny tapered dowels, no bigger than the tip of a toothpick, pricked through the back and front, which are the pivot on which many a certificate and expert opinion turns.

Learned articles have been written about the geometrical significance of these ‘piercings’ at either end of the back plate. I don’t know geometry, but for me, pins still have a fair fascination. It seems de rigueur to use them in modern making, since they are an observed feature of Stradivari’s work. If you make an instrument on a Cremonese-type mould, you are often offering up the plates to the ribs and mould, and also removing them. It’s very useful to have an accurate location point, so that the whole assembly fits together in exactly the same way each time.

Ever since the days of Andrea Amati and Gasparo da Salò, the accepted method has been to drill a tiny hole near the edge straight into the blocks. A nail will hold things together perfectly well until final assembly, when a little wooden pin will fill the hole. Andrea Amati placed it well inside the purfling, plain to see. But the Brothers Amati began to move it as close as possible to the purfl ing, presumably to make it less obvious. Stradivari tried to hide it underneath the purfling. But if you make the hole too near the edge, it will come through the fragile rib on the other side, rather than into the block itself. So Stradivari contented himself with tucking it half-under the purfling, leaving a little semicircle still visible. But it is a sine qua non of Stradivari, and of all Cremonese making. If it ain’t there, it ain’t Cremonese.

But then there was a change. Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ gave up trying to hide the pins, moving them safely away from the fragile edge and into full sight – and so did many subsequent makers. That alters the idea learnt by most makers that in order to make a violin in the true Cremonese way, you must assemble the soundbox completely and put the purfling in last, otherwise you can’t lay the purfling over the pins. But it was only Nicolò Amati and Stradivari who did that. Most didn’t.

Early makers were surprisingly relaxed about letting such points show in their otherwise painstaking work. When we look at a new violin, we are aware of these pins, and we check they are neatly done. We perhaps forget that they are in fact a flaw. I still find it painful to drill holes in my violins. My instincts are to make the work as perfect as possible, to hide these purely constructional elements. But that is not the way the old masters worked.

Read: Jacob Stainer: Micro-CT analysis of top-block and pins

Read: Trade Secrets: Making purfling with fish glue

Discover more lutherie articles here

This article is from the November 2013 issue of The Strad

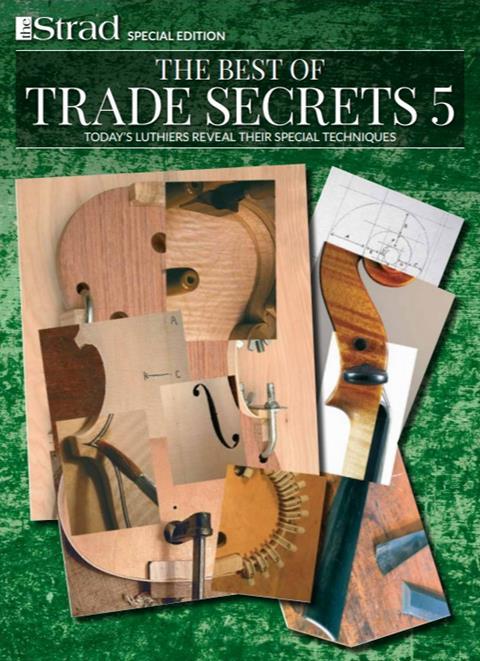

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stinged instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet