John Dilworth celebrates the more humble yet essential parts of a violin in the first of a series of articles from 2013

Discover more lutherie articles here

This article is from the January 2013 issue of The Strad

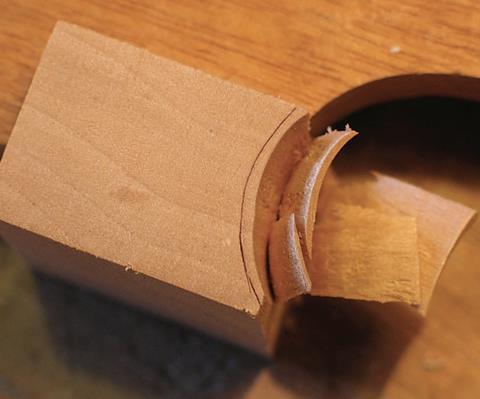

Corner-blocks are exciting. They are the start of a new violin, a new build. Take a nice clean block of spruce or willow, dress it on all sides, and pop it on the mould. The woodworking skills are simple and straightforward, but don’t take them for granted. We’ve already made a few decisions. What is our model? What sort of mould? And spruce or willow? Scraps of spruce litter the workshop, so it’s easy to pick up a little cleaved piece from the floor – I mean the scrap box – with a good straight grain, ready to go. That’s the way it must it have been for Amati or Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, and for most makers in history, I suppose. But you do get fussy. The split has to be right, and the grain able to support the fine point of the rib.

Maybe you’re making a Stradivari model, and he always used willow. So do we take the trouble to be authentic? Yes, of course we do! I think Stradivari introduced willow as the choice material for this humble, subordinate part of the structure. Typical. He didn’t do things the easy way, but the best way. You don’t have lumps of willow offcuts around the workshop unless you go out and get them specifically for purpose. But willow is good: the grain is more homogeneous than spruce, and can be cut (with a sharp enough tool) in almost any way you like. So thanks to Stradivari, willow has become part of a violin maker’s stock.

My old teacher, the wonderful Wilf Saunders, used to saw up old willow cricket bats – a recycler decades before eco-awareness, although I think that as a child of the last period of austerity, he just liked to use things that didn’t cost money. My stock comes from a tree that was blown down on the local riverside in the great storm that battered southern England in 1987. It didn’t cost me anything either, except a gratuity to the council workers who were sawing it up.

So we have a mould loaded up with blocks, and it looks fine. Blocks with a history, but also, as I said, on the start of a new adventure. Take a nice sharp gouge and carve that sweet curve for the C-bout rib. The block falls off because you didn’t glue it firmly enough and you swear and cuss and wonder exactly what it is you’ve learnt after doing the same thing every single time. It’s a reminder that we’re fallible, that a little cube of willow wood, insignificant as it may seem, is smarter than we are, and needs just as much care and consideration as that self-important bass-bar or that flashy scroll.

Read: Cutting corner blocks: inside the Markneukirchen violin factory

Read: Trade Secrets: Repairing damaged blocks

Discover more lutherie articles here

This article is from the January 2013 issue of The Strad

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stinged instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet