Exactly 280 years ago in December, master violin maker Antonio Stradivari met his end. Here Andrew Dipper recounts how the changes that took place in Cremona during his final years influenced the creation of his later masterpieces

The following is an extract from a longer article in The Strad December 2017 – to read it in full, download the issue on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

Many past writers and violin enthusiasts, including F.J. Fétis, the Hills and Vuillaume, instigated or propagated the common 19th-century belief that Antonio Stradivari spent a life of peaceful solitude under idyllic conditions in a serene Italian town, making masterpieces in a quaint old workshop. The Romantic imagination saw violin masterpieces and imagined the master that validated the myth. However, just as we have with the lives of Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo, under a more powerful lens and a broader historical analysis we can expose another reality. Stradivari’s work was brought to completion in a common struggle against the exigencies of the time, in a city depopulated by recent plagues and war, with a populace that suffered under the yoke of the declining Spanish empire. If these events were not restrictions enough, the political carousels that preceded and followed every change of monarch turned enormous tides in the affairs of the Italian cities and delivered ever more punishing blows to existing supply chains, markets and trade routes.

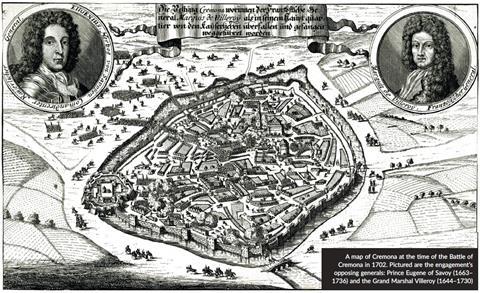

Antonio’s 92 years run from the uncertain date and place of his birth during the epidemics, war and siege of Cremona in the late 1640s, to his demise in Cremona under Austrian occupation on 18 December 1737. His life and the success of his business were carried on during the Italian campaigns of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), the annexation of Spanish Lombardy by the Austrians in 1713, and the War of the Polish Succession (1733–5), in which the armies of Savoy, Spain and France battled those of the Austro-Hungarian empire in an ever-widening spiral of sophisticated warfare. In the last upheaval at the end of Stradivari’s life the movement of foreign troops and mercenaries, combined with climatic instability, contributed to outbreaks of deadly infectious diseases and influenza in Cremona. In the years 1733 to 1738 these events must have seemed like the end of the world for the Cremonese.

To read the full article download The Strad’s December 2017 issue on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

No comments yet