Despite having been examined by some of the best-known experts in history, the violin has spent centuries largely hidden – until now. John Dilworth examines one of the least regarded instruments by the Cremonese master

This is an extract of a six-page focus in The Strad’s November 2018 issue, with more photos and close examinations of the violin itself and its historical record. To read in full, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

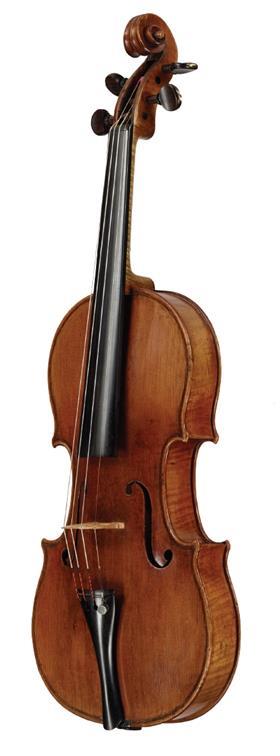

It is very, very rare these days to come across a largely unknown Stradivari. It is too easy to think that, after all the efforts of dealers, collectors, experts and researchers, the list of known authentic instruments must be pretty well complete. But then, sometimes, somewhere, an instrument arrives out of the blue that is so clearly genuine and original that the records have to be revised.

What is all the more amazing is that such an overlooked instrument should prove to be such a pure and outstanding example of the master’s work. This violin of 1724 has remained hidden from public view for most of its life. It was in the private possession of an Italian family for over one and a half centuries, from around 1810 until the 1970s, and was acquired by the present owner in 2004.

Nevertheless it has been noted and authenticated several times during this long period by some of the most important connoisseurs of the day, from Count Cozio di Salabue to Charles-Eugène Gand, Alfred Hill and Charles Beare.

…

Since 2004 it has been owned by Desmond Cecil. A professional violinist from 1965 until 1970, he studied in Switzerland with Max Rostal but subsequently joined the UK Diplomatic Service, and was awarded the CMG in 1995. He himself has written and published a detailed monograph on his violin [which is available on The Strad Shop], by which it has finally entered the public realm after 200 years of virtual anonymity.

The startlingly pure state of this violin perfectly reflects its sheltered history. Long years in the possession of generations of one family have allowed woodworm to infiltrate the front, although fortunately not the back, but the freshness and beauty of the varnish have been perfectly preserved, along with the fine detail of the woodwork.

The sound of this long-dormant instrument is also re-emerging.

Playing the ‘Cecil’

Desmond Cecil, owner of the eponymous violin, describes its tone colour and the experience of playing the instrument

When I first played this violin, its sound was – understandably, given its many years of inactivity – somewhat muted, particularly higher up on the A and D strings, although the E and G strings were still quite powerful. One well-known soloist had tried the violin but with only limited tonal results. I put on lower-tension strings, and the well-known luthier David Hume fitted a slightly more resonant bridge, but otherwise I did nothing apart from playing it very regularly – and of course learning the technique of how to coax, rather than force, the sound out of a Stradivari.

Over a period of some two to three years’ regular playing, the violin came back to life. It blossomed out with a full, sweet sound across the whole register, with an excellent resonance (Nachklang) and carrying power – and with the characteristic ‘darker’ sound that is much sought after in the later Stradivaris.

Recently I was invited to play the solo violin in charity concerts in two medium-sized concert halls – the Oxford Town Hall and the Pittville Pump Room in Cheltenham. Notably, audience members at both concerts commented that the violin sounded full, warm and ringing in tone, and also that the pianissimo high notes carried very clearly to the back of the hall.

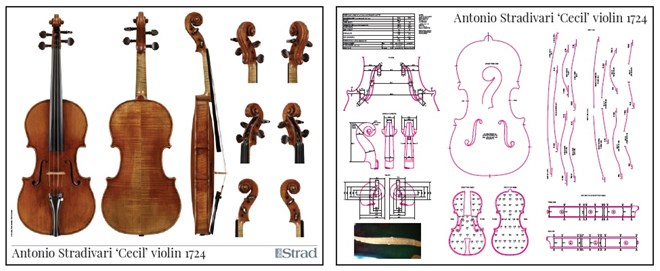

The ‘Cecil’ is the subject of The Strad’s latest poster. To order a rolled copy, visit The Strad Shop

No comments yet