An elaborately decorated 18th-century bow has evaded serious scrutiny – until now. In this article from the April 2014 issue, Matthew Zeller details the analysis of the many types of wood it contains

Discover more lutherie articles here

The ‘Spanish Court’ bow of c.1700 is an exceptionally interesting item. Now part of the permanent collection of the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota, it was brought to light by the famed violin expert Alfred Hill in Madrid. Hill ascertained that it had originally been part of the collection of instruments (two violins, two violas and a cello) made by Antonio Stradivari for the Spanish court. The instruments were finally purchased for the Court in 1772, long after Stradivari’s death, during the reign of King Charles III of Spain. The Hills suggest this may have been because the Crown Prince, the future King Charles IV, was himself a violin player. It is also possible that the Crown Prince himself acquired the bow when he lived in Italy prior to 1788.

The frog of the ‘Spanish Court’ bow is adorned with the Crown Prince’s coat of arms on one side, and the initials C.A.R. on the other. As Charles Beare noted in his 1993 book Antonio Stradivari: The Cremona Exhibition 1987, although no surviving bows can be attributed with absolute certainty to Stradivari, the ‘Spanish Court’ bow can nevertheless lay a strong circumstantial claim.

Whether or not the bow does indeed come from Stradivari’s workshop, it is a fascinating product of its time. A full detailed analysis of the materials used in its making would help to give an insight into the working practices of luthiers during that period, and allow us to compare the original craftsmanship with that of the bow’s later additions.

PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION

The stick is fluted on all eight facets along its entire length from handle to head, including through the frog seating. Its most striking feature is the intricate inlaid wood: a repeating pattern of tri-band tiles. The button is inlaid in the same manner as the stick, and an identical inlay pattern is present on the frog, through the centre line of the throat and heel. It is clear from the similarities in the materials and workmanship that the same hand performed the tri-band inlay on both the frog and the stick.

Evidence suggests that the bow was heavily played using an 18th-century Italian-style bow hold, where the bow is held higher up on the stick than the traditional modern French grip. The fluting and inlay tiles are worn evenly throughout the handle area, indicating a period of heavy use after the inlay was performed. The head shows patterns of wear consistent with years of use and, unfortunately, careless rehairing. The nose has been shortened and rounded off, and some of the inlay tiles are missing or have been replaced.

The head shows patterns of wear consistent with years of use and, unfortunately, careless rehairing

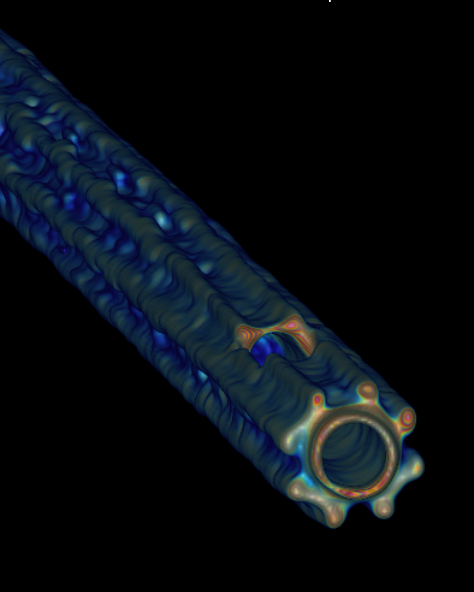

Before the wood identification was begun, the ‘Spanish Court’ bow underwent a CT scan to determine if there were any hidden issues of condition that might affect the decision of which inlay tiles to remove temporarily for wood analysis (figure 1). It was discovered that the tiles inlaid into the frog seating of the stick, where the frog slides back and forth during tensioning, had been worn down to a fraction of their original dimensions. This also indicates a period of regular use after the tiles were inlaid. For this reason, we removed the tiles on the back side of the frog instead.

IDENTIFYING THE WOODS

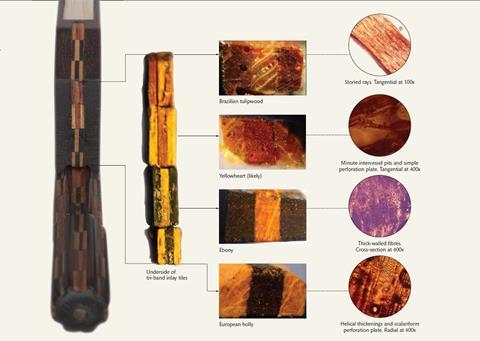

There are four different types of tri-band inlay tiles used throughout the bow. Each tile is composed of three individual pieces of wood: a centre strip with flanking strips of an opposing colour. The tiles correspond inversely to each other in two sets: white–black–white followed by black–white–black; and yellow–red–yellow followed by red–yellow–red.

One tile of each type was temporarily removed from the frog with a tool made especially for the purpose, and samples were excised from the underside of each tile. Cross-sectional, radial and tangential samples were obtained, averaging 1–2 sq mm and less than 0.1mm thick. The samples were mounted in water on glass slides and examined on a visible light microscope at 40x, 100x and 400x magnifi cation.

For identification (figure 2), we used the wood anatomy features list of the International Association of Wood Anatomists and the ‘Inside Wood’ database published online by North Carolina State University.

The white wood is European holly, Ilex aquifolium. This wood was easy to work: cross-sectional pieces did not flake or chip, and radial and tangential samples were easily excised. Initial inspection revealed vessel groupings in radial rows and wide rays of two distinct sizes, the taller of which were over 1mm. An identifying characteristic observed under microscopic examination was the presence of helical thickenings in vessel and fibre elements.

The black wood is ebony, Diospyros spp. Identification of the particular species is not possible with the samples obtained. It is possible that it is African ebony, Diospyros crassiflora, or Mauritius ebony, Diospyros dictyoneura, a species that was heavily imported to Europe by the Dutch beginning in the 16th century. On unaided inspection, it is uniformly jet black, dense and tightgrained. Under the knife, it had the familiar feel of ebony that an experienced violin or bow maker would expect.

The yellow wood is likely yellowheart, Euxylophora paraensis, also called Brazilian satinwood, pau amarello and canarywood. Unfortunately the samples obtained did not contain enough anatomically identifiable features to make a conclusive judgement. However, the features observed, combined with the availability of yellowheart as an inlay wood in both Italy and Spain during the 18th century, allow for a reasonable diagnosis that this wood is yellowheart.

The red wood is Dalbergia decipularis, commonly known as Brazilian tulipwood, pau rosa or bois de rose. The quality is first-rate: it is evenly coloured throughout each piece, dense and straight-grained. Some distinguishing anatomical features present include vessels of two different diameters, which are surrounded by parenchyma (fundamental) elements and storied (tier-like) rays and fibres.

Read: Lost Guarneri documents resurface after nearly a century

Read: On the trail of a 1708 Stradivari: J.T. Carrodus and a mystery violin

FROG

The frog, which was previously misidentified as mahogany, is actually made of lightly figured snakewood. The stick and button cores are well-figured snakewood and have been previously identified as such.

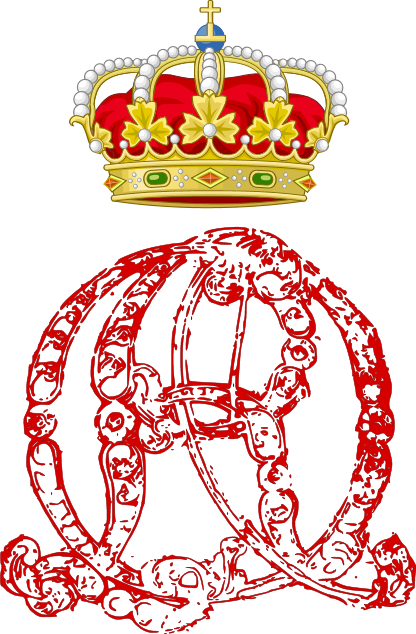

The coat of arms, as it appears on the bow frog, is a close match with that of the Prince of Asturias – not the Royal Arms of Spain. The Prince of Asturias is the title given to the heir to the Spanish throne, in this case Charles IV, who held the title from 1759 to 1788. The same crown has been used from the reign of Philip V (beginning in 1700) to the present day. It has a cross at its apex and the top is closed by four rosettes, three of which are visible. (The King’s crown, by contrast, is closed by eight rosettes.)

The shield on the bow is almost an exact match with that of Castile and León traditionally present in the coats of arms used by the Prince of Asturias – only the shape differs. The shield, divided into quarters, features the three-tiered castle of Castile and rampant lion of León. The supporters on the coat of arms are a bit of an enigma. They look similar to the eagle wings present in the older coats of arms of the Catholic monarchs, rather than the Pillars of Hercules used by Charles IV. They may also be related to the angel wings present on the ornamented version of the Royal Arms that has been in use since the reign of Philip V. Vestiges of this shape can be seen in the supporters of the abbreviated Royal Arms used during the reign of Charles III.

The craftsmanship of the coat of arms is crude compared with that of the bow

The differences between the coat of arms as it appears on the ‘Spanish Court’ bow and the various historic coats of arms of the Prince of Asturias may be explained by the difficulty of inlaying a precise replica, and the limited skill of the craftsman. Apart from the central ebony cross, all the elements of the bow’s coat of arms can be reasonably associated with those of the Prince of Asturias. The cross is not present in any form of the coat of arms from the mid-15th century to the present day. However, one can speculate that it is a gap-filling measure used by the inlay artist to push the larger pieces against the walls of the mortise. The craftsmanship of the coat of arms is crude compared with that of the bow, especially when the excellence of the fluting and the elegant chamfers on the frog throat are taken into account.

As shown in figure 3, the coat of arms is composed of four main wood types. The individual pieces of wood comprising it could not be safely removed without risking damage. Therefore, microscopic anatomical analysis of these woods was not available. However, examination with a 10x hand lens and approximately 200–250x surface magnification yielded pertinent results: the woods present in the coat of arms are not the same woods used in the tri-band tile inlay.

The wood used for the supporters, most of the crown, and the shield quarters containing the lions appears similar to the African wood Ilomba, Pycnanthus angolensis. This wood has multiseriate rays (more than one cell wide) that are greater than 1mm tall, and vessels approximately 200 microns in diameter and well over 800 microns long. It is strikingly different from any other wood used in the construction and ornamentation of the bow. The shield quarters containing the castles appear to be made of a member of either the Dalbergia or Swietenia genera because of the wood’s storied ray structure and reddish–brown colouring. The ray structures look similar to Dalbergia decipularis, but the vessels are quite large and uncharacteristic of Brazilian tulipwood. It may be bigleaf mahogany, Swietenia macrophylla: the short storied rays and large vessel sizes support this theory, but the colour is a little too pink to be typical of this wood.

A section of one of the crown rosettes and various sections of small inlay in the castles look somewhat similar to European holly, but the colour and texture of the wood do not support that theory. The wood used for the bottom of the crown and the connecting arms between the supporters and the shield do not contain enough identifi able material to support a theory without microscopic analysis. Fragments of cross-sectional slices of wood used in the castles also do not provide enough information to venture an educated guess. The lions are made of a matrix of some type, probably animal glue mixed with wood dust or a colouring agent. The final identifiable wood in the coat of arms, used for the central cross, is ebony: Diospyros spp.

The monogram on the reverse of the frog (figure 4) bears a strong resemblance to that used by Charles IV when he was King of Spain (figure 5). It is less refined and less ornamented, but the same elements are present in both monograms. The letters ‘C’ and ‘R’ along with the theme of encirclement clearly link the two designs. The monogram is not inlaid with wood but a filler of a different composition from the lions on the shield. It cannot be discerned whether the inlay of the monogram was performed at the same time as that of the coat of arms, or by the same hand.

Enough elements are present to conclude that the coat of arms and monogram on the bow are those of Charles IV of Spain when he was Prince of Asturias, from 1759–88. The closed crown with four rosettes indicates his status as the Crown Prince. The shield is consistent with this, and the monogram appears to be an earlier version of the monogram Charles IV used after 1788 as the King of Spain. Although a positive identification of the woods used in the coat of arms is not yet possible, it is clear that they are not the same woods used in the tri-band tile inlay.

The bow’s overall style is indicative of bows made throughout most of the 18th century and the wear patterns are consistent with the Italian-style bow grip that was popular during that time. The use of different woods indicates that the inlay of the tri-band tiles and the coat of arms was not performed at the same time; the differences in craftsmanship also testify to this. The coat of arms and monogram were probably added between 1759 and 1788, most likely when the bow came into the possession of Charles IV.

In the future, I plan to do archival research to track the provenance of the ‘Spanish Court’ bow before it was acquired by Alfred Hill. I hope to discover references to the bow in luthiers’ work logs, and to determine the date of acquisition by the Spanish court. A positive attribution to Antonio Stradivari’s workshop would undoubtedly have far-reaching implications: not only would it rewrite some of the history and philosophy surrounding the world’s greatest violin maker, but it could also reshape the timeline of the bow’s evolution.

A full report on the wood identification is available through the National Music Museum, Vermillion, South Dakota, US

Read: How Nicolò Amati’s ‘Romanov’ viola survived its own turbulent history

Read: Curiouser and curiouser: the 1672 ‘Gustav Mahler’ Stradivari viola

Discover more lutherie articles here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stringed instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet