The British dendrochronology expert explains his latest research, revealing how wood from one source can appear in centuries-old instruments made thousands of miles apart

Discover more lutherie articles here

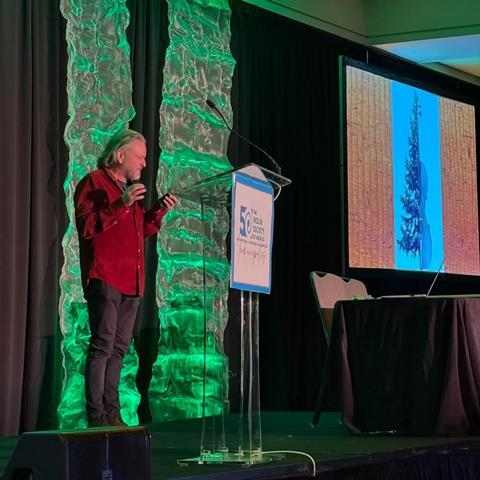

While the Violin Society of America’s convention continues, one of the most fascinating lectures so far has come from by violin maker and dendrochronologist Peter Ratcliff. Over the past two decades, Ratcliff has examined thousands of instruments and built up possibly the world’s most extensive dendrochronological database – so much so that he can now detect relationships between instruments across all kinds of territories that had hitherto been completely unsuspected by researchers.

‘Large-scale cross-matching’ involves comparing the ring patterns of the spruce of a violin’s top plate with all the others in the database. In some cases, the ring patterns match so precisely that the wood must have come from the same tree. In many cases, the forest it came from can be ascertained.

‘These concealed wooden relationships amount to genuine factual associations linking different makers, instruments and locations,’ said Ratcliff, giving the example of a Carlo Rugeri violin containing spruce from the same tree as Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’. ‘Sometimes you get a same tree match with instruments from different countries,’ he went on. ‘So I started developing theories on the trade of wood across Europe over the centuries.’

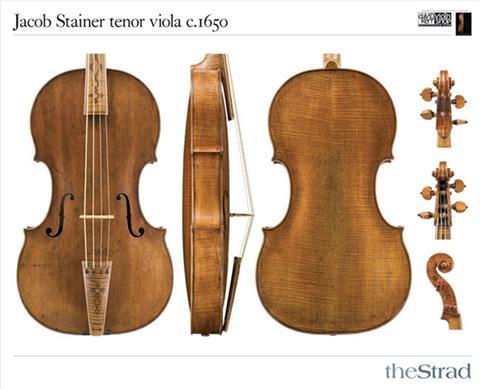

He gave several examples of ‘batches’ of wood that had been distributed far and wide. One of the first batches of spruce that can be identified comes from the Austrian Alps, a geographical area that was known for its wood to makers to the north and to the south. The wood used by Jacob Stainer (c.1618–83) cross-matches very well with that of Nicolò Amati (1596–1684), as well as with lutes and viols made 100 years earlier or more.

A second highly recognisable batch comes probably from Germany’s Black Forest, and is found in instruments from the Low Countries from 1650 to 1720. This wood can also be found in instruments from the British Isles at the same time. One may conclude that access to the Rhine river played a significant role in transporting this wood all the way from southern Germany up to the Netherlands and Belgium – especially since this wood is not found in Italian instruments.

‘This information could be very useful when an expert is torn between attributing an instrument to Venice, Rome, Amsterdam or London,’ said Ratcliff, pointing to an example: ‘I’ve seen a number of 17th-century English instruments, with double purfling and nice varnish, sold off as Brescian.’

Read: Ask the Experts: is dendrochronology useful in valuing an instrument?

Read: Dendrochronology should be more widely used to authenticate violins

Video: A fresh look at the dendrochronology of the ‘Messiah’

The next batch of wood appears in France, in instruments made between 1725 and the Revolution year of 1789. This wood was used universally in France and nowhere else, and was apparently kept under the control of the French guilds until they were abolished in the Revolution. At that point the wood vanished, never to be seen again. According to Ratcliff, most of this wood is unlikely to be genuine spruce.

Another batch again is common to instruments from the Italian peninsula. The likely source is the northern Italian Alps, and it ended up in workshops in Venice, Genoa, Rome and as far south as Naples. ‘It’s clear that wood from same forest ended up in cities 700km apart,’ said Ratcliff. ‘The sudden demise and collapse of availability of this wood may simply be attributable to the death of a single wood dealer. Unfortunately the names of wood dealers are hard to come by in the records: we know of one dealer named Banchetti in Brescia, who was named in a letter by Paolo Stradivari.’

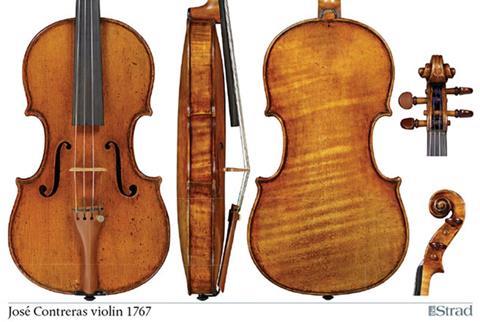

Conversely, luthiers in Florence and around Tuscany were also using wood from the Apennines; so did makers in Cremona and Mantua from 1772 onwards, when the previous sources of spruce were no longer available. While its use around 1700 is not common, Girolamo Amati II used Apennine wood on one violin after his move to Piacenza. And more intriguingly, the Spanish luthier José Contreras (sometimes called ‘the Spanish Stradivari’) acquired some of this wood as well.

In a similar arrangement to the French, the Spanish guilds seem to have had control of the wood supply in the 18th century: guild members weren’t allowed to source their own wood. The wood most Spanish luthiers was, according to Ratcliff, ‘tight-grained and very like spruce, but it isn’t spruce. It’s difficult to say exactly where it was sourced from, but it may have been from central Spain, in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains north of Madrid. It didn’t travel outside Spain and disappears at the end of the century.’ Contreras, however, managed to escape the guild’s stranglehold on wood through his privileges working for the Spanish court. He, and other court makers such as Vicente Assensio, sourced wood from Italy instead.

From the mid-19th century onwards, Italian makers were mostly using German wood rather than spruce from the Dolomites. This remained the case for around 100 years, well into the 20th century.

‘This is all valuable, unbiased information for everyone from experts to dealers and auction houses,’ Ratcliff concluded this part of his presentation. ‘Of course, there’s a lot more to discover as regards the sources of wood, but this is a synopsis of what I’ve been able to perceive thus far.’

Read: From the Archive: a violin by José Contreras

Read: In Focus: a 1784 Vicente Assensio violin

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stringed instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

Violin Society of America’s 50th convention kicks off in Indianapolis

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently reading

Currently readingWhere the wood came from: Peter Ratcliff speaks to the VSA

- 6

No comments yet