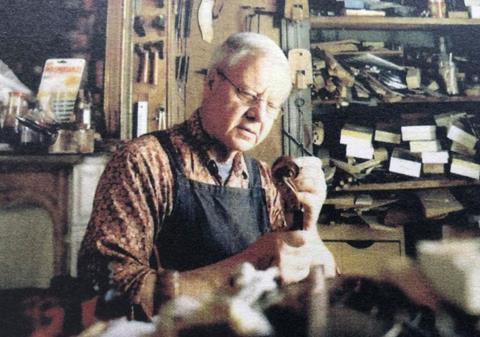

The grandson of Eugène Sartory, Dupuy was an accomplished violin maker and author in his own right

French violin maker Philippe Dupuy died on 5 April at the age of 88. The grandson of Eugene Sartory, he was the author of an illustrated history of his grandfather’s life, which was published in 2019. Since his retirement in 2006 he had been living in Ardèche, in the south of France.

Born on 6 October 1932, Dupuy was the son of violin maker Georges Dupuy, a founder member of the International Association of Violin and Bow Makers (EILA). Aged 14 he travelled to Mirecourt to study violin making under Léon Mougenot. He then worked for a number of years for Walter Hamma in Stuttgart, Germany, before returning to his father’s workshop in the Rue de Rome, Paris. He became the master of the workshop in 1968 following Georges Dupuy’s death, and continued to run the business until his retirement almost 40 years later. He was joined by bow maker Christophe Schaeffer in 1978, and Pierre Caradot in 2000. Caradot called him ‘a very elegant and refined person, with a huge amount of culture and an “English” sense of humour’.

Dupuy was also an active member of EILA, as well as secretary of the Groupement des Luthiers et Archetiers d’Art de France (GLAAF) for many years. He was also involved in the project to create a national violin making school in Mirecourt, which opened its doors in 1970.

Read: Influential Italian luthier Renato Scrollavezza has died

Read: Spanish luthier Ramon Pinto has died at 89

Read: Double bass maker Patrick Charton has died

Dupuy was an occasional researcher and contributor to journals such as L’Âme et la corde. On his book, Eugène Sartory: Documents and photographs concerning his life and work, The Strad’s reviewer Philip Brown said: ‘This book is a touching tribute to the renowned bow maker Eugène Sartory, penned by his maternal grandson, Philippe Dupuy. It does not attempt to cover the output of the great archetier’s work, but instead seeks to paint a picture of Sartory the man, through letters, writings, postcards and diary notes. The image of Sartory that develops is charming and sometimes surprising… The book is a work of art in itself. Such quality makes handling this publication a treat.’

No comments yet