In this interview feature by Barbara L. Sand, Joey Corpus, who has died at the age of 59, discusses his late start as a musician, living with a disability, and his teaching philosophy

Joey Corpus’s cover is rapidly being blown. Known by some of his students as The Underground Guru, or The Secret Weapon, his name is becoming increasingly familiar outside the tight little circle of his fervent admirers. In part, this is due to the fact that about a year ago he crossed the great divide between New Jersey and New York, and getting to his home on the Upper West Side is a snip compared to making the trek to the hinterlands across the Hudson. Corpus is the kind of teacher who says, ‘Sure, come on up,’ when he gets an emergency call at 8pm from, say, someone with an audition the next day, and it was largely due to affectionate pressure from the original band of hardy travellers (‘Joey, we hate to tell you, but we hate coming to New Jersey,’) that he decided to make the move.

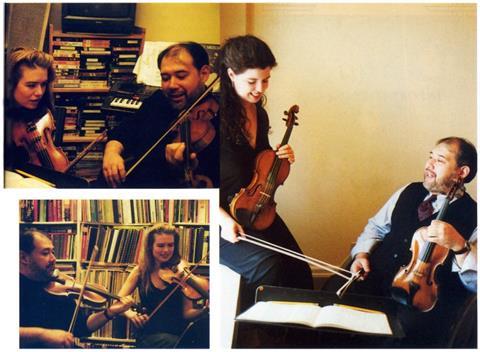

Corpus has a disarming grin and an outgoing manner. He loves good talk, good food and chess, and is reputed to be a master magician. The students with whom I spoke cannot say enough about him both as teacher and as friend. Corpus talks freely and without a tinge of self-pity about the tragedy that shaped the course of his life. When he was eleven years old, he barely survived a car accident — an accident which took the life of his mother. It took many years and many operations for him to recover, although he was never to regain the use of his legs. (Itzhak Perlman has more mobility than Corpus because he is able to get up with the aid of his crutches.) As a result, Corpus, who is now 44, is confined to a wheelchair. Well, perhaps ‘confined’ is the wrong word to use for Corpus. It doesn’t seem to fit. The move to living in New York was a major decision, and he finds himself totally thrilled with Manhattan and all it has to offer.

‘I think this is the greatest city in the world,’ he says. ‘Every sidewalk has a ramp – I can get pretty much wherever I want. The move has been very liberating. It’s changed everything. I love meeting people, and it’s so easy here.’ Manhattan buses are equipped to take care of wheelchairs, and at his suggestion, Corpus and I decided to meet for our initial interview in my mid-town Manhattan apartment, at which he arrived by public transport. No problem! as New Yorkers like to say.

By his own account, Corpus exhibited absolutely no musical ability as a child

Corpus was born in the Philippines. The eldest of six children, he grew up in a musical household. Family friends came to play chamber music, his father was an amateur jazz musician and both grandfathers had been concert violinists. A brother, who lives in Spain, has a highly successful career as a violinist. By his own account, Corpus exhibited absolutely no musical ability as a child. ‘Piano lessons were a nightmare,’ he says. ‘I didn’t even really learn how to read notes, because I would read the fingerings. I just didn’t like sitting there and playing. My father used to tell me the story of taking me to a violin concert, where I fell asleep right at the very beginning. So a year or so after the accident, when I told him I want to play the violin, he said, “Oh yeah. Right.” But Corpus senior soon realised his son was serious, and resurrected an instrument that had belonged to one of the grandfathers and had it put back in shape. The boy had never touched a violin before, let alone held one under his chin, thus giving the lie to those who say you have to start when you are practically pre-natal. At 14, he had recovered sufficient strength to start studying in earnest, and the following year he won a competition and came to the attention of Edgar Schenkman, who was on a visit to the Philippines. Schenkman, then Conductor of the Juilliard School Orchestra, heard him play and offered him a full scholarship to go to the United States and study with Dorothy DeLay. But, as Corpus characteristically understates it, ‘the physical situation was not good.’ He was still far too ill at that point to go anywhere.

I ask Corpus how he had been able to learn when he was in such dire straits physically. ‘I had very little sitting time every day to practise, so basically, I had to come up with a way to be efficient,’ he says. ‘I loved to practise, but I was limited, so I tried to figure out ways so that within a half an hour or an hour I would be able to do as much as I could. I guess I was quite obsessed with it, and I thought about it all the time. I had one teacher I saw every week, so whatever little I learned from him I applied to everything. Later, I was able to practise for a more extended time — a few hours — but it was always somewhat confined. I learnt to practise lying down. I would lie on my side, my left elbow propped up, and just practise because I like to do it so much. I would practise scales and rhythms. I practised a lot by just looking at the music.’

Truthfully, I did not think of ‘career’, I just wanted to learn how to play better

By the time he reached his late teens, Corpus’s health was greatly improved and he was playing a fair number of concerts and recitals. ‘To me, there was very little difference between practising and playing — I derived the same amount of enjoyment from both of them,’ he says. ‘I didn’t envision much of a future for myself in the Philippines. There was not much to musical life there, certainly not at that time. Truthfully, I did not think of ‘career’, I just wanted to learn how to play better. That was my idée fixe.’ Throughout his late teens and early 20s, Corpus was largely self-taught. In 1982, at the age of 24, he came to the United States with his brother, an art student, and went to Philadelphia to study with Jascha Brodsky at the New School of Music.

‘It was great,’ he says. Brodsky was a wonderful teacher. It sort of reinforced everything I had been doing. I don’t mean to be arrogant, but many of the things I was learning I had sort of figured out, or come to very similar conclusions, working on my own.’ Apparently Corpus himself started teaching almost the minute he arrived at the school. He and his classmates would get together and play for each other, and almost without anyone being aware of it, he became the one to whom the others would turn for suggestions. Corpus stayed in Philadelphia for the next seven years, after which he moved, with his brother, to New Jersey.

Of the group of students with whom I spoke, Lara St. John, who has won a number of important competitions and now tours all over the world, has spent the longest time with Corpus – 15 years – and still sees him from time to time. ‘He explains the “why” of everything,’ she says. ‘When I was a kid, I thought I was being made to do scales as a punishment. Joey explained to me that intonation is all in the ear. If your scales are not in tune, your ear is not learning and you will play out of tune. I had an instant realisation of what he was saying. I am very tall, and have long arms and long fingers. This may be hard to believe, but somehow I was able to play without shifting. When I got to be 18, it stopped working. Joey took me back to the beginning. We spent months just going from first to third position. His level of patience is extraordinary. If it hadn’t been for him, I might have chucked the whole thing out of the window.’

He was so kind and incredibly patient and had a genuine concern for me

Sisterhood is powerful. Louise Owen, assistant concertmaster of the hit Broadway musical ‘The Producers’, is a close friend of St. John, and went to Corpus on her recommendation at a time of great trouble. She had suffered an injury to a nerve-ending and had to stop playing for a couple of years. ‘Lara said “You should go and see Joey. If you go and play open strings, it will be the best lesson of your life.” And it was. He gradually helped me build up my strength. He was so kind and incredibly patient and had a genuine concern for me. The fact that I had been unable to play for such a long time constituted a huge psychological barrier. Joey took my hand and walked me through the process from the beginning, telling me I could go as slowly as I needed to. It was incredible. I can now play better than I ever thought I would be able to do before I had the problem.’

Wen Qian, assistant concertmaster of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, met Corpus in Philadelphia shortly after she came to the US from China in 1988. ‘I didn’t realise how much of an impact his teaching had on me until recently,’ she says. ‘He set me in a very good direction by setting up a strong foundation and showing me how to approach the instrument technically. Joey tackles things from many angles — his way of solving problems is very flexible. He is systematic, but he sees into each individual. He sees the big picture and knows where to guide you. People follow him like flies. He’s also a very good psychiatrist and helps to build your confidence. He is an amazing person. He can make a misty picture clear.’

Katharine Gowers is currently touring the major capitals of the world in a piano quartet celebrating the 70th birthday of Alfred Brendel, with Brendel himself at the helm. The tour grew out of two highly successful concerts in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall and Carnegie Hall in New York in 1999. Like Louise Owen, Gowers met Corpus through Lara St. John. In 1993, Gowers, who lives in London, was studying in the US and went along for the ride one afternoon with St. John for her lesson. Gowers ended up playing for Corpus herself and found his approach so absorbing that she stayed the night (Corpus was still in New Jersey at that time), ready to plunge in again the next day. She got so hooked on working with Corpus in this concentrated fashion (a process he also enjoys), that two years ago she managed to get private sponsorship to spend a month with him, seeing him three or four times a week for about four hours at a stretch. Gowers made a similar journey in September 2000, for a three-week stint, and again for ten days last April, a trip that was abbreviated because of the death of her father. She says she learned something new each time.

His ego is not involved at all – his focus is entirely on helping you

‘The first time I went, I thought I had a left-hand problem,’ Gowers says. ‘Instead, Joey spent a month on my bow arm and transformed how I felt physically and mentally. Joey’s overriding qualities are his patience and his great sense of humour. His ego is not involved at all – his focus is entirely on helping you. Joey is pathologically modest. We have fights to see who can come out saying the worst things about ourselves. We are extremely competitive about how awful we are. I call him The Oracle, and he calls me The Scribe, because I take notes furiously during the lessons. He is phenomenally intelligent.’

Corpus’s students cover a wide spectrum. He teaches all ages but is reluctant to take beginners because he feels they are a speciality. ‘I will take the ones who can do Vivaldi concertos,’ he says. ‘I love to develop talented kids at that level. Some people come to me who are just preparing for some audition. Some because they are having pains in the arms, or are uncomfortable with playing. Others because they need some kind of structure – they don’t know how to practise. I work on different levels with different emphases. It depends on what is needed. Not everyone will sound good playing with the same fingering. You have to find something that suits them. Perhaps they are not comfortable with the so-called standard bow grip. To me, it’s all about making music. So lessons are never just, OK, this is a difficult passage, let’s try to clean it up. It’s, OK, what are we trying to do with the passage? How does it fit with the phrase or the overall structure of the piece? That’s the goal.

‘Certain technical things become difficult when you start to put in the musical factor. For example, vibrato. You can actually teach someone to have a very good vibrato. But the difficulty lies in applying it musically. You cannot play the same vibrato all the time. Whether you want to slow it down, or play it narrower or wider, is all dependent on the musical context, and you must have that control. Whatever you want to do with a phrase, you must do it with the bow and the left hand — they work together. Often, I hear people try to play say forte only with the bow. In other words, they think sheer volume without thinking about the added breadth of sound that vibrato can have. Or playing piano, some violinists play soft, but it’s not really soft because they are still vibrating as though they are playing forte. Everything has to start with the musical demands. By concentrating on “I want to play this note with this volume with this sort of vibrato. I want to phrase it this way,” you are immediately thrown into the process of making music, not just playing notes. The job is important, the career is very, very important, but you have to be a musician. Everything else will come after that.’

Watching Corpus teach, it is clear that he is in complete authority. Not in the sense of being even remotely overbearing – his warmth and humour remain intact – but simply that he knows what he is talking about and how to get it across. No mysteries, no-ambiguities. If there is a problem, either technical or musical, there is a solution. If this sounds matter-of-fact and business-like, in a way it is, but what Corpus does varies enormously with each individual. ‘The greatest motivation is to see themselves improve right away,’ Corpus says of his students. ‘To get them from point A to point B within the time of the lesson is very rewarding for me, as well as for them. It is important for them to have that experience because they realise “oh, if I practise this, I know I will get better”. And I want it to be immediate. I expect that during the lesson, whatever we work on, it will get better. I expect it of them,’ he adds emphatically. ‘They must.’

No comments yet