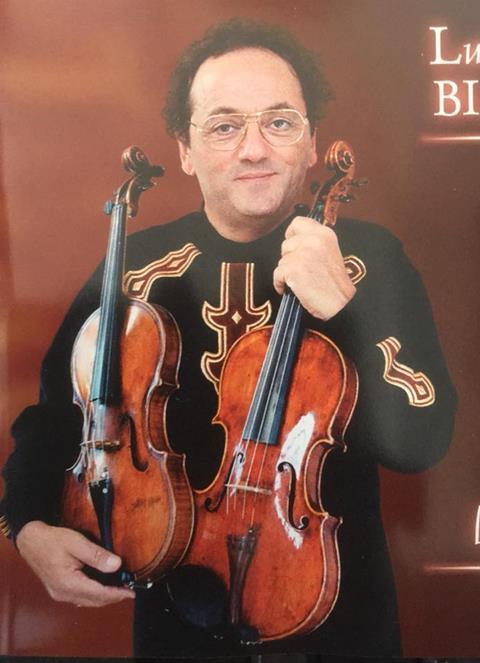

Menuhin protégé who in later years swapped fluidly between violin and viola, and whose career was punctuated by the thefts of two famous instruments

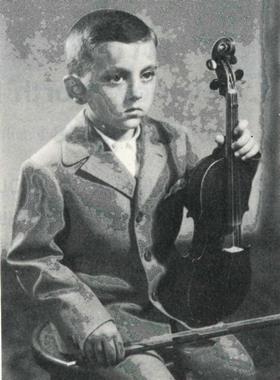

Born on New Year’s Day 1945 in Rimini to a composer father and pianist mother, Luigi Alberto Bianchi was surrounded by music from the start, and it wasn’t long before he developed into a violin prodigy.

His turn to the viola came almost by chance, when he enrolled at music college in Rome to find all the violin classes oversubscribed and instead was taken on by violist Luigi Ghezzi. ‘He had only three viola pupils and he could devote hours and hours to me,’ Bianchi told The Strad in 1989.

‘With him I formed a real technique, playing Sevcík, Kreutzer – no performances, just technique. I still played the violin but we had such a good relationship that I changed to the viola because of him.’

At the Accademia di Santa Cecilia he went on to study with the great Renzo Sabatini who in turn set up a life-changing audition with Yehudi Menuhin, starting a mentoring relationship which led Bianchi to describe Menuhin as a ‘real godfather’ – his own father having died when he was just 11.

Menuhin invited him to play at the Bath Festival in 1968, involved him in chamber music projects, wrote an introduction for his LP of the two Brahms Sonatas; played and recorded the Mozart Sinfonia Concertante with him; and was also responsible for his meeting Georges Marci, who later became his wife. Meanwhile Bianchi had won the Carl Flesch Competition in 1970, playing the Walton Concerto in the presence of the composer, was a member of the Quartetto di Roma piano quartet for eight years, became principal viola of the Orchestra Sinfonica della RAI, all the while building a reputation as a viola soloist.

Then came a shock: his 1595 Antonio and Girolamo Amati viola, known as the ‘Medicea’ or the ‘del Crocifisso’ after the crucifix decoration on its back (pictured), was stolen from his car in the Piazza della Scala in Milan in 1980. Despite being probably the most easily recognisable viola in the world, it disappeared until 2006 (and it wasn’t until 2013 that the dispute with the insurance company was resolved and Bianchi was able to take ownership of the instrument once more).

The event led him to give up the viola and return to the violin, effectively restarting his career as an unknown quantity. ‘I had my reasons,’ he told The Strad, claiming that he ‘could not find an instrument that I liked after the theft of the Amati.’

With the insurance money from the Amati he acquired a 1692 Stradivari, and later upgraded to the ‘Colossus’ of 1716, paying a then record £440,000 for the long pattern violin previously owned by Viotti, his pupil Pierre Baillot, and Jacques Thibaud. ‘For a viola player, a violin is always a toy and so I always like to play large models,’ he said.

Then in 1998 came a second shock when it too was stolen, this time from his mother’s house in Rome along with two Peccatte bows – and so far remains missing.

It seems the search for a new instrument led Bianchi to the third phase of his career, where he played both violin and viola, often appearing with both on recordings and indeed live, playing the first half of a recital on one instrument and the second on the other. He claimed the only real difficulty was in changing bow because of the weight difference.

Bianchi taught internationally, made several recordings, was an authority on Paganini and wrote a monograph on Alessandro Rolla, Paganini’s teacher.

He died on 3 January 2018, two days after his 73rd birthday.

No comments yet