The Hill’s trained bow maker made a vital contribution to the trade during a long career, writes John Milnes

‘If you can see something wrong, put it right. If you could see it, other people could see it. The last thing you wanted was to be criticised for being sloppy. It was instilled in you’ – Bill Watson (Interview 2013)

The bow maker Bill Watson has died at 88. He was part of the last flowering of bow making at W.E. Hill & Sons that started with Samuel Allen back in the 1880s and was guided by William Retford for sixty years until Retford’s retirement in 1956. Bill benefitted from a thorough apprenticeship at Hills from 1945, and a further eleven years of intensive teaching and experience under Retford and the bow shop manager, Arthur Bultitude.

Bill’s early life did not predict a lifetime as a craftsman. His parents were in the printing trade in Ealing, west London. The Second World War disrupted his education and he spent many hours in a shelter listening to the bombers overhead. At 14 his father sent him to be a plumber but he lasted just one morning as a plumber’s mate, deciding that standing up to his knees in water in a flooded basement was not for him – a streak of decisiveness that would serve him well.

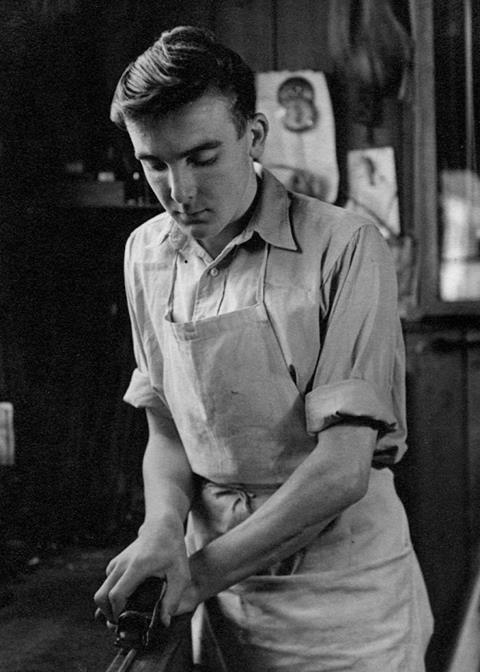

Social life got going again after the war and young Bill joined the Boys Brigade, a version of the scout movement. By chance a Brigade leader, Arthur Bultitude, suggested Bill come to work with him at Hill’s violin workshops in Hanwell. Though he had lived all his life Hanwell, Bill had never heard of the ‘fiddle factory’ run by W.E. Hill & Sons to support their shop in Bond Street. He had no proven aptitude for woodwork but accepted Arthur’s invitation.

As the first new apprentice at the firm for seventeen years, Bill started as the general dogsbody, sweeping floors and setting fires, as well as being taught how to sharpen and use the tools. He might have learned to make violins or instrument cases but didn’t like the men running the violin or case shops. He also might have been sacked, since there was no formal apprenticeship contract and the case shop manager thought he would never be a craftsman as he was naturally left handed. However the pugnacious irascible William Retford, who was the dominant influence in the bow shop, noticed that the new apprentice was doing his best and could listen to advice. Retford showed a friendly interest, so Bill asked to work for him.

By now 70 years old, Retford had great self-confidence. On bow matters the firm’s boss, Alfred Hill, used to say ‘It’s your department. I trust you, do whatever you think best.’ Because young Bill was responsive to guidance, Retford would call him to the bench and show him a collection of fine bows, detail by detail. ‘His eye was so keen, he would steer you in the right direction … If you tried your hardest, he would go to no end of trouble.’

For eleven years after apprenticeship Bill worked steadily in the firm and mastered all aspects of bow making. He was set the tricky task of cutting out the gold fleur-de-lys to be inlaid in the best bow frogs. With characteristic persistence he progressed from taking an hour and a half (breaking many blades and files on the way) to completing the job in fifteen minutes.

By 1962 both his mentors, Retford and Bultitude, had left Hills. Bill had a wife and two daughters to support and decided that his best course was to set up independently. From his homes in Buckinghamshire, Cornwall, and finally Dorset came many fine bows over the next fifty years.

After leaving Hills, Bill took no apprentices of his own and did not pass on his skills directly. But he lectured and gave presentations to the British Violin Making Association (BVMA), the Entente Internationale des Luthiers et Archetiers (EILA) and the Violin Society of America (VSA). He was always happy to help the new generation of bow makers and to share what he had learned.

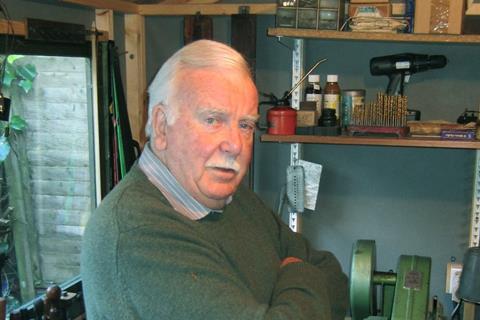

He also made a vital contribution to the history of bow making in Britain when in 2009 he agreed to be interviewed for the BVMA book, The Hill Bow Makers, which came out in 2016. He took to this project enthusiastically, giving interviews, checking details and searching his archives for photos. And he agreed to make a film in 2012 demonstrating all he had been taught about the Hill approach. A team of final-year students from the film school at Falmouth University spent weeks squeezed into his tiny workshop, creating several hours of archive footage of Bill’s knowledge.

Bill remained at his bench until nearly the end of his life. His second wife Janet cared for him, and she and his daughters Christine and Angela gathered in January 2019 with other friends and colleagues to say goodbye to a great craftsman.

1 Readers' comment