Read about the tools of the great violinist’s trade in this extract from January 2011

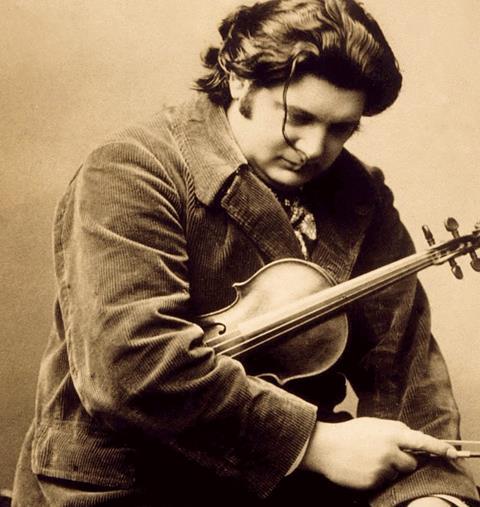

The following is an extract from the article ’Great Violinists: Eugène Ysaÿe’ which featured in the January 2011 issue. To read the full article, click here

INSTRUMENTS

Ysaÿe’s first violin of note was a c.1754 Guadagnini (see The Strad Calendar, 2010), procured from a Hamburg pawnbroker, but in 1896 he persuaded a pupil to take it in exchange for her Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ (plus some money to make up the difference in value; she also gained a husband when she married his brother Théophile). This 1740 instrument served him for the rest of his career, and was later owned by Isaac Stern. Ysaÿe also owned the ‘Hercules’ Stradivari (1732) from 1895 until it was stolen from his box at the St Petersburg Imperial Opera House in 1908 (it reappeared at a Paris dealer’s in 1925 and was later owned by Henryk Szeryng, who donated it to the City of Jerusalem for use by the leader of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra). But he preferred to play the more agile ‘del Gesù’, reserving the heavier-going Stradivari as his back-up in case a string broke.

REPERTOIRE AND RECORDINGS

Ysaÿe stood out from both his predecessors and successors for the high-brow nature of his concert programming, which included whole recitals of sonatas, something of a rarity in the 1890s. He was at the forefront of performances of new music, taking part in the world premieres of such iconic works as Franck’s Violin Sonata (its composer’s wedding present to the violinist), Debussy’s String Quartet (with his own Ysaÿe Quartet) and Chausson’s Poème. In the concerto repertoire he excelled in the Classical and early Romantic masterworks, and was especially admired for his Beethoven. Ysaÿe’s own best-known works, the six Solo Sonatas, were composed in the mid-1920s, when his own playing career was largely over. By dedicating each to a major violin-playing colleague (including Thibaud and Enescu) it was as if he was handing over the mantle to a new generation.

His recorded legacy unfortunately includes none of these epochmaking works and, limited by the acoustic recording technology of the second decade of the 20th century, is of necessity dominated by short, encore-type pieces, including miniatures by Fauré and Wieniawski, the finale of the Mendelssohn E minor Concerto with piano, and arrangements by Kreisler and Joachim. All that survives, from sessions at the Columbia Studios in the Woolworth Building, New York, in 1912–14, is contained on a hard-to-find single CD released in 1996 by Sony Classical (also included are four French pieces with Ysaÿe conducting the Cincinnati orchestra). The transfers can’t do much about the ever-present shooshing noise, but the style, immaculate phraseology and power of Ysaÿe’s playing still manage to break through the aural rainstorm.

No comments yet